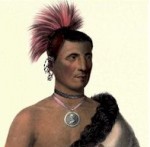

A Pawnee Chief

We regret that so few particulars have been preserved of the life of this individual, who was one of the most prominent men of his nation, and whose character afforded a favorable specimen of his race. He was a person of excellent disposition, who, to the qualities proper to the savage mode of life, added some of the virtues which belong to a more refined state of society. But such is the evanescent nature of traditional history, that, while we find this chief invariably spoken of with high commendation, we have been scarcely able to trace out any of the circumstances of his life.

Peskelechaco was a noted war-chief of the Pawnees, who visited Washington City as a delegate from his nation in 18__. We have had frequent occasions of remarking the salutary effect produced upon the minds of the more intelligent of the Indian chiefs and head men, by giving them the opportunity of witnessing our numbers and civilization; our arts, our wealth, and the vast extent of our country. The evidences of our power, which they witness, together with the conciliatory effect of the kindness shown them, have seldom failed to make a favorable impression. Such was certainly the case with this chief, who, after his return from Washington, acquired great influence with his tribe, in consequence of the admiration with which they regarded the knowledge he had gained in his travels. He had spent his time profitably in observing closely whatever passed under his notice, and, in proportion to his shrewdness and intelligence, his opinions became respected.

He spoke frequently of the words he had heard from his great father, the President of the United States, who had, in pursuance of the benevolent policy which has governed the intercourse of the administration at Washington with the Indians, admonished his savage visitors to abandon their predatory habits, and cultivate the arts of peace. Peskelechaco often declared his determination to pursue this salutary advice. He continued to be uniformly friendly to the people of the United States, and faithful to his engagements with them, and was much respected by them. He was a man of undoubted courage, and esteemed a skilful leader.

The only incident in the active life of this chief, which has been preserved, was its closing scene. About the year 1826, a war-party of the sages marched against his village with the design of stealing horses, and killing some of his people. The assailants were discovered, and a severe battle ensued. The chief, at the head of a band of warriors, sallied out to meet the invaders, and the conflict assumed an animated and desperate character. Having slain one of the enemy with his own hand, he rushed forward to strike the body, which is considered the highest honor a warrior can gain in battle. To kill an enemy is honorable; but the proudest achievement of the Indian brave is to strike, to lay his hand upon, the slain or mortally wounded body of his foeman, whether slain by himself or another. To strike the dead is, therefore, an object of the highest ambition; and, when a warrior falls, the nearest warrior of each party rushes forward, the one to gain the triumph, and the other to frustrate the attempt. Peskelechaco was killed in a gallant endeavor to signalize himself in this manner.