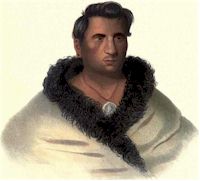

Ongpatonga

An Omakas Chief (Omaha)

There are few aboriginal chiefs whose character may be contemplated with so much complacency as that of the individual before us, who is not only an able but a highly estimable man. He is the principal chief of his nation, and the most considerable man among them in point of talent and influence. He uses his power with moderation, and the white men who have visited his country all bear testimony to his uniform fair dealing, hospitality, and friendship. He is a good warrior, and has never failed to effect the objects which he has attempted; being distinguished rather by the common sense and sagacity which secure success, than by the brilliancy of his achievements.

While quite a young man, he performed an exploit which gained him great credit. The Omaha had sent a messenger of some distinction upon an embassy to the Pawnee Loups, who, instead of receiving him with the respect due to his character, as the representative of his nation, treated him with contempt. Ongpatonga, though young, was a chief of some distinction, and immediately took upon himself to revenge the insult. He deter mined to do this promptly, before the aggressors could be aware of his intention, and while the sense of injury was glowing in the bosoms of his people. Placing himself at the head of the whole population of his village, men, women, and children, he proceeded to the Pawnee town, and attacked it so suddenly, and with such a show of numbers, that the inhabitants deserted it without attempting a defense. He then destroyed the village and retired, taking with him a considerable booty, consisting chiefly of horses.

The Omaha inhabit the shores of the Missouri River, about eight hundred miles above its confluence with the Mississippi. They of course hunt over those beautiful and boundless prairies which afford pasturage to the buffalo, and are expert in the capture of that animal, and the management of the horse. They have but one permanent village, which consists of huts formed of poles, and plastered with mud. A fertile plain, which spreads out in front of their town, affords ground for their rude horticulture, which extends to the planting of corn, beans, pumpkins, and watermelons. This occupation, with the dressing of the buffalo skins, procured in the previous winter’s hunt, employs the spring months of the year; and, in June, they make their arrangements for a grand hunting expedition. A solemn council is held in advance of this important undertaking, at which the chiefs, the great warriors, and the most experienced hunters, deliberately express their opinions in relation to the route proposed to be pursued; the necessary preparations, and all other matters connected with the subject. A feast is then given by an individual selected for the purpose, to which all the chief men are invited, and several of the fattest dogs are roasted for their entertainment. Here the principal chief introduces again the great subject of debate, in a set speech, in which he thanks each person present for the honor of his company, on an occasion so important to the nation, and calls upon them to determine whether the state of their stock of provisions will justify their remaining longer, to allow the squaws time to weed their corn, or whether they shall proceed at once to the pastures of the game. If the latter be the decision of the company, he invites them to determine whether it would be advisable to ascend the running water, or seek the shores of the Platte, or extend their journey to the black hills of the south-west, in pursuit of wild horses. He is usually followed by some old chief, who compliments the head man for his knowledge and bravery, and congratulates the tribe on their good fortune in having so wise a leader. Thus an Omaha feast very much resembles a political dinner among ourselves, and is improved as a fit occasion for great men to display their eloquence to the public, and their talent in paying compliments to each other. These consultations are conducted with great deco rum, yet are characterized by the utmost freedom of debate; every individual, whose age and standing are such as to allow him, with propriety, to speak in public, giving his opinion. A sagacious head man, however, is careful to preserve his popularity by respecting the opinion of the tribe at large, or, as we should term it, the people; and for that purpose, ascertains beforehand, the wishes of the mass of his followers. Ongpatonga was a model chief in this respect; he always carefully ascertained the public sentiment before he went into council, and knew the wishes of the majority in advance of a decision; and this is, probably, the most valuable talent for a public speaker, who may not only lead, by echoing the sentiments of those he addresses, but, on important points, insinuates with effect, the dictates of his own more mature judgment.

After such a feast as we have described, others succeed; and the days of preparation for the grand hunt are filled with games and rejoicings; the squaws employing themselves in packing up their movables, and taking great care to make themselves important by retarding or accelerating the moment of departure. At length the whole tribe move off in grand cavalcade, with their skin lodges, dogs, and horses, leaving not a living thing in their deserted village, and proceed to the far distant plains, where the herds of buffalo ” most do congregate.” About five months in the year are spent by this nation at their village, during which they are occupied in eating, sleeping, smoking, making speeches, waging war. or stealing horses; the other seven are actively employed in chasing the buffalo or the wild horse.

The Omaha have one peculiarity in their customs, which we have never noticed in the history of any other people. Neither the father-in-law nor mother-in-law is permitted to hold any direct conversation with their son-in-law; it is esteemed indelicate in these parties to look in each other’s faces, or to mention the names of each other, or to have any intercourse, except through the medium of a third person. If an Omaha enters a tent in which the husband of his daughter is seated, the latter conceals his head with his robe, and takes the earliest opportunity to withdraw, while the ordinary offices of kindness and hospitality are performed through the female, who passes the pipe or the message between her father and husband.

Ongpatonga married the daughter of Mechapa, or the Horsehead. On a visit to his wife one day, he entered the tent of her father, unobserved by the latter, who was engaged in playing with a favorite dog, named Arrecattawaho, which, in the Pawnee language, signifies Big Elk being synonymous with Ongpatonga in the Omaha. This name the father-in-law was unluckily repeating, without being aware of the breach of good manners he was committing, until his wife, after many ineffectual winks and signs, struck him on the back with her fist, and in that tone of conjugal remonstrance which ladies can use when necessary, exclaimed: “You old fool! have you no eyes to see who is present? You had better jump on his back, and ride him about like a dog!” The old man, in surprise, ejaculated ” Wah!” and ran out of the tent in confusion. We know scarcely any thing so odd as this singular custom, which seems to be as inconvenient as it is unmeaning.

The Big Elk has been a very distinguished orator; few uneducated men have ever cultivated this art with more success. We have before us a specimen of his oratory, which is very creditable to his abilities. In 1811, a council was held at the Portage des Sioux, between Governor Edwards and Colonel Miller, on the part of the American government, and a number of Indian chiefs, of different nations. One of the latter, the Black Buffalo, a highly respected Sioux chief, of the Ietan tribe, died suddenly during the conference, and was buried with the honors of war. At the conclusion of the ceremony, Ongpatonga made the following unpremeditated address to those assembled: “Do not grieve. Misfortunes will happen to the wisest and best of men. Death will come, and always comes out of season. It is the command of the Great Spirit, and all nations and people must obey. What is past, and cannot be prevented, should not be grieved for. Be not discouraged nor displeased, that in visiting your father here, you have lost your chief. A misfortune of this kind, under such afflicting circumstances, may never again befall you; but this loss would have occurred to you, perhaps, at your own village. Five times have I visited this land, and never returned with sorrow or pain. Misfortunes do not flourish particularly in one path; they grow every where. How unhappy am I that I could not have died this day, instead of the chief that lies before us. The trifling loss my nation would have sustained in my death, would have been doubly repaid by the honors of such a burial. They would have wiped off every thing like regret. Instead of being covered with a cloud of sorrow, my warriors would have felt the sunshine of joy in their hearts. To me it would have been a most glorious occurrence. Hereafter, when I die at home, instead of a noble grave, and a grand procession, the rolling music, and the thundering cannon, with a flag waving over my head, I shall be wrapped in a robe, and hoisted on a slender scaffold, exposed to the whistling winds, soon to be blown down to the earth my flesh to be devoured by the wolves, and my bones trodden on the plain by wild beasts. Chief of the soldiers! (addressing Colonel Miller,) your care has not been bestowed in vain. Your attentions shall not be forgotten. My nation shall know the respect that our white friends pay to the dead. When I return, I will echo the sound of your guns.” Had this speech been uttered by a Grecian or Roman orator, it would have been often quoted as a choice effusion of classic eloquence. It is not often that we meet with a funeral eulogium so unstudied, yet so pointed and ingenious.

This chief delivered a speech to the military and scientific gentlemen who accompanied Colonel Long in his expedition to the Rocky Mountains, in 1819-20, in which he asserted, that not one of his nation had ever stained his hands with the blood of a white man.

The character of Ongpatonga is strongly contrasted with that of Washinggusaba, or the Black Bird, one of his predecessors. The latter was also an able man, and a great warrior, but was a monster in cruelty and despotism. Having learned the deadly quality of arsenic from the traders, he procured a quantity of that drug, which he secretly used to effect his dreadful purposes. He caused it to be believed among his people, that if he prophesied the death of an individual, the person so doomed would immediately die; and he artfully removed by poison every one who offended him, 01 thwarted his measures. The Omaha were entirely ignorant of the means by which this horrible result was produced; but they saw the effect, and knew, from mournful experience, that the dis pleasure of the chief was the certain forerunner of death; and their superstitious minds easily adopted the belief that he possessed a power which enabled him to will the destruction of his enemies. He acquired a despotic sway over the minds of his people, which he exercised in the most tyrannical manner; and so great was their fear of him, that even when he became superannuated, and so corpulent as to be unable to walk, they carried him about, watched over him when he slept, and awoke him, when necessary, by tickling his nose with a straw, for fear of disturbing him toe abruptly. One chief, the Little Bow, whom he attempted ineffectually to poison, had the sagacity to discover the deception, and the independence to resist the influence of the impostor; but being unable to cope with so powerful an oppressor, he withdrew with a small band of warriors, and remained separated from the nation until the decease of the Black Bird, which occurred in the year 1800. It is creditable to Ongpatonga, who shortly after succeeded to the post of principal chief, that he made no attempt to perpetuate the absolute authority to which the Omaha had been accustomed, but ruled over them with a mild and patriarchal sway.

In a conversation which this chief held, in 1821, with some gentlemen at Washington, he is represented as saying “The same Being who made the white people made the red people; but the white are better than the red people;” and this remark has been called a degrading one, and not in accordance with the independent spirit of a native chief. We think the comment is unjust. Having traveled through the whole breadth of the United States, and witnessed the effects of civilization, in the industry of a great people, he might readily infer the superiority of the whites, and make the observation with a candor which always formed a part of his character. But, it is equally probable, that the expression was merely complimentary, and was uttered in the same spirit of courtesy with the wish, which he announced at the grave of the Ietan, that he had fallen instead of the deceased.

This chief is a person of highly respectable character. His policy has always been pacific; he has endeavored to live at peace with his neighbors, and used his influence to keep them upon good terms with each other. He has always been friendly to the whites, and kindly disposed towards the American government and people; has listened to their counsels, and taken pains to disseminate the admonitions which have been given for the preservation and happiness of the Indian race. He is a man of good sense and sound judgment, and is said to be unsurpassed as a public speaker. He bears an excellent reputation for probity; and is spoken of by those who know him well, as one of the best men of the native tribes. He is one of the few Indians who can tell his own age with accuracy. He is sixty-six years old.