Adario, A Tionontate chief, known also as Kondiaronk, Sastaretsi, and The Rat

Hodge, Frederick Webb, Compiler. The Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office. 1906.

A Tionontate chief, he had a high reputation for bravery and sagacity, and was courted by the French, who made a treaty with him in 1688 by which he agreed to lead an expedition against the Iroquois, his hereditary enemies. Starting out for the war with a picked band, he was surprised to hear, on reaching Cataracouy 1, that the French were negotiating peace with the Iroquois, who were about to send envoys to Montreal with hostages from each tribe. Concealing his surprise and chagrin, he secretly determined to intercept the embassy. Departing as though to return to his own country in compliance with the admonition of the French commandant, he placed his men in ambush and made prisoners of the members of the Iroquois mission, telling the chief of the embassy that the French had commissioned him to surprise and destroy the party. Keeping only one prisoner to answer for the death of a Huron who was killed in the fight, he set the others free, saying that he hoped they would repay the French for their treachery. Taking his captive to Michilimackinac, he delivered him over to the French commander, who put him to death, having no knowledge of the arrangement of peace. He then released a captive Iroquois whom he had long held at his village that he might return to inform his people of the act of the French commander. An expedition of 1,200 Iroquois fell upon Montreal Aug. 25, 1689, when the French felt secure in the anticipation of peace, slew hundreds of the settlers and burned and sacked the place. Other posts were abandoned by the French, and only the excellent fortifications of others saved them from being driven out of the country. Adario led a delegation of Huron chiefs who went to Montreal to conclude a peace, and while there he died, Aug. 1, 1701, and was buried by the French with military honors. (F. H.)

Adario, Chief of the Dinondadies

Drake, Samuel G. Indian Biography, containing the lives of more than two hundred Indian Chiefs, pp. 9-11. Pub: Boston, Josiah Drake. 1832.

Dinondadies, Colden. Tionontazed, Charlavoix. About 1687, the Iroquois, from some neglect on the part of the governor of New York, owing, says Smith, 2) to the orders of his master, ” king James, a poor bigoted,-popish, priest ridden prince,” were drawn into the French interest, and a treaty of peace was concluded. The Dinondadies were considered as belonging to the confederate Indians, but from some cause they were dissatisfied with the league with the French, and wished by some exploit to strengthen themselves in the interest of the English. For this purpose, Adario put himself at the head of 100 warriors, and intercepted the ambassadors of the Five Nations 3 from Carolina, which added another, and hence afterwards they were properly called the Six Nations.)) at one of the falls in Kadarakkui River, killing some and taking others prisoners. These he informed that the French governor had told him, that 50 warriors of the Five Nations were coming that way to attack him. They were astonished at the governor’s perfidiousness, and so completely did the plot of Adario succeed, that these ambassadors were deceived into his interest. In his parting speech to them he said, “Go, my brethren, I untie your bonds, and send you home again, though our nations be at war. The French governor has made me commit so black an action, that I shall never be easy after it, till the Five Nations shall have taken full revenge.” This outrage upon their ambassadors, the Five Nations doubted not in the least to be owing to the French governor’s perfidy, from the representations of those that returned. They now sought immediate revenge; and assembling 1200 4 of their chief warriors, landed upon the island of Montreal, 26 July, 1688, while the French were in perfect security, burnt their houses, sacked their plantations, and slew all the men, women, and children without the city. A thousand persons were killed in this expedition. In October, following, they attacked the island again with success. These horrid disasters threw the whole country into the utmost consternation. The fort at Lake Ontario was abandoned, and 28 barrels of powder fell into the hands of the confederate Indians. Nothing now saved the French from an entire extermination from Canada, but the ignorance of their enemies in the art of attacking fortified places.

Kondiaronk

Garrad, Charles. Petun to Wyandot: The Ontario Petun from the Sixteenth Century, pp. 540-541. University of Ottawa Press. 2014.

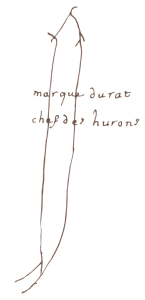

Kondiaronk was a war chief 5 of the Beaver Clan of the Turtle phatry, and Tribal Orator. His totem signature on the 1701 Treaty is a beaver pelt 6.

Sastaretsi was a Civil Chief 7 of the Deer Clan and Nation. His totem signature on Treaty No. 2 is the head of a deer with a full spread of antlers 8.

To illustrate a point about matrilineal descent, the Baron Lahontan 9 wrote of a hypothetical marriage between Adario (Rat, Kondiaronk) and a daughter of Sastaretsi. This confusion is probably because Kondiaronk spoke for and as Sastaretsi, and with the authority of Sastaretsi, during negotiations in Montreal in 1682 10, also likely in 1697, and certainly in 1700 and 1701. On none of these occasions did the person Sastaretsi himself travel to Montreal, but his title and authority did, as used for the name of the tribe 11. It was usual for the “principal person,” even when present, not to speak but to address councils through an orator “in the time-honored fashion of the wise leader who relies upon his executive assistant to make his speeches” (as with Dekanawida and Hiawatha)12. As Tribal Orator, Kondiaronk was “great in the Huron councils of war and peace,” “a fine man if ever there was one…who revolutionised the World.” In his role as orator he was termed Soüoïas (Muskrat, The Rat)13. Perhaps then presentation style customarily employed by orators to deliver their addresses was not appropriate for a Head Civil Chief 14.

In August 1682, it is recorded that:

“Some Hurons, or Tionnontatez, comprised under the name of their chief Sataretsi (spelling varies), arrived at Montreal… to the number of ten canoes, communicated their first word… through their orator, Soüoïas, in French The Rat… Speaking in the singular number under the name Sataretsi – they had come down on the request of Onontio their father… to learn his will… The same Soüoïas, after a pause, said: Onontio, thy son Saretsi styled himself formerly thy brother; but he has ceased to be such, for he is now thy son… Onontio, thy son Sataretsi hath an upright mind… Sataretsi stands before the eyes of Onontio, his father. 15

In response to the County de Frontenac’s accusation that the Hurons had “carried belts into suspected places… Soüoïa replied, that it was true that Sataretsi had been to the Seneca… only to arrange their unfortunate affairs.” 16

In the manner of Wyandot speech, the Orator Souaias was speaking for the entire tribe collectively under the name of its chief, Sastaretsi, who was not personally present.

The name Soüoïas (also Souoia, Souaiti) in the above document “might be a bad representation (not uncommon in the New York Colonial Documents) of the Huron term for muskrat – ‘tsisk8aia'”17. As Kondiaronk, Soüoïas is recorded in particular as being associated with the negotiations with the Iroquois and French at Montreal which led to the Great Treaty of 1701 due to the fact that he died there 18.

In his summary of the 1682 negotiations, John G. Shea made it clear that Sastaretsi and Soüoïas were two separate men: “Sastaretsi was regarded at this time as head chief or king, and all was done in his name. Ten canoes bearing his word, Soüoïas or the Rat being the speaker, attended an Indian congress at Montreal, Aug. 15, 1689” 19.

Another diplomatic mission from the Wyandots of Michilimackinac to the French Governor in Montreal was made in 1697, but the name of the participants have not survived. At this even, “the Hurons presented three Belts the object of which was to confirm Onnontio in the good-will he always entertained toward them, and to assure him of the fidelity of Sataressy (that is the name of the whole Nation in general) despite the secret intrigue of the Baron, one of their chiefs, and of his family” 20. The wording surely implies that Sastaretsi the person was not one of the delegates and allows the assumption that Kondiaronk was the spokesman. To call an entire nation by the name of the principal chief was a normal practice, and the Wyandots were referred to as Sastaretsi on several occasions as, “The Baron, a Huron of Missilmakinac, but who is not, however, of the family of Sataretsy, which gives the name to the Nation”21.

The Baron Lahontan wrote of Kondiaronk, who was possibly his adopted brother, by the name Adario (“great and noble friend”) by which he was probably known to his own people 22 It is very probable that Kondiaronk/Adario was a relative of Sastaretsi, it being the custom for the Tribal Orator to be a relative of the civil chief 23. Lahontan hinted at one place that Adario may have been Sastaretsi’s father and brothers-in-law would be a different clan to the Deer clan to which the title and mother of Sastaretsi belonged. The Tribal Orator in 1721 was the uncle of the Sastaretsi of that time. In 1786 the Tribal Orator was Scotosh, thought to be a half-brother to Sastaretsi, and additionally a nephew of and adopted as a son by Tarhe.

In 1700, Kondiaronk attended peace negotiations in Montreal between the French, allied tribes, and the Iroquois. He was described in the English colonial records as “The Rat, the Chief of the Hurons” 24, but by Charlevoix as “the deputy and chief of the Thionnontates Hurons.” In Montreal again in 1701, he was described as “the Rat, orator and chief of the delegation from the Hurons of Michilimackinac“25. Sastaretsi himself was not present on either occasion.

Citations:

- modern Kingston, Ontario[

]

- Hist. N. Y. 56 (4th edition[

]

- These associated nations were -known by this name until 1712, at which time they were joined by the Tuskaroras ((Tuscaroras[

]

- So says Colden, but Charlevoix says 200. There can be no doubt but that the truth is between them, as there is ample room.[

]

- Boucher 2002: 253[

]

- illustrated by Bonvillian 1989: 78[

]

- Walsh 1997: 49[

]

- Canada 1891: lxi, 1-3; Curnoe 1996: 113; Public Archives Canada 1974: 64; Walsh 1997: 49[

]

- 1970 2: 461[

]

- Thwaites in Lahontan 1905 2: 461fn1[

]

- NYCD 1855c: 667, 672[

]

- Kehoe 2006: 227[

]

- Boucher 2002: 253; Crompton 1925: 73; Sioui 1992: 65-68[

]

- Jameson 1838 3: 138; Tailhan in Blair 1911: 54fn30[

]

- NYCD 1855c: 178-179[

]

- Jameson 1838 3: 138; Tailhan in Blair 1911: 54fn30[

]

- Steckley pers. comm.[

]

- Fenton 1969 2: 320-323[

]

- Shea 1861: 264, 1998: 4[

]

- NYCD 1855c: 667[

]

- Hale 1894: 12; NYCD 1855c: 667, 672[

]

- Sioui 1992: 66, 74, 1999: 10[

]

- Sioui 1999: 23n138[

]

- NYCD 1855c: 715-720[

]

- Charlevoix 1870 5: 110, 141[

]