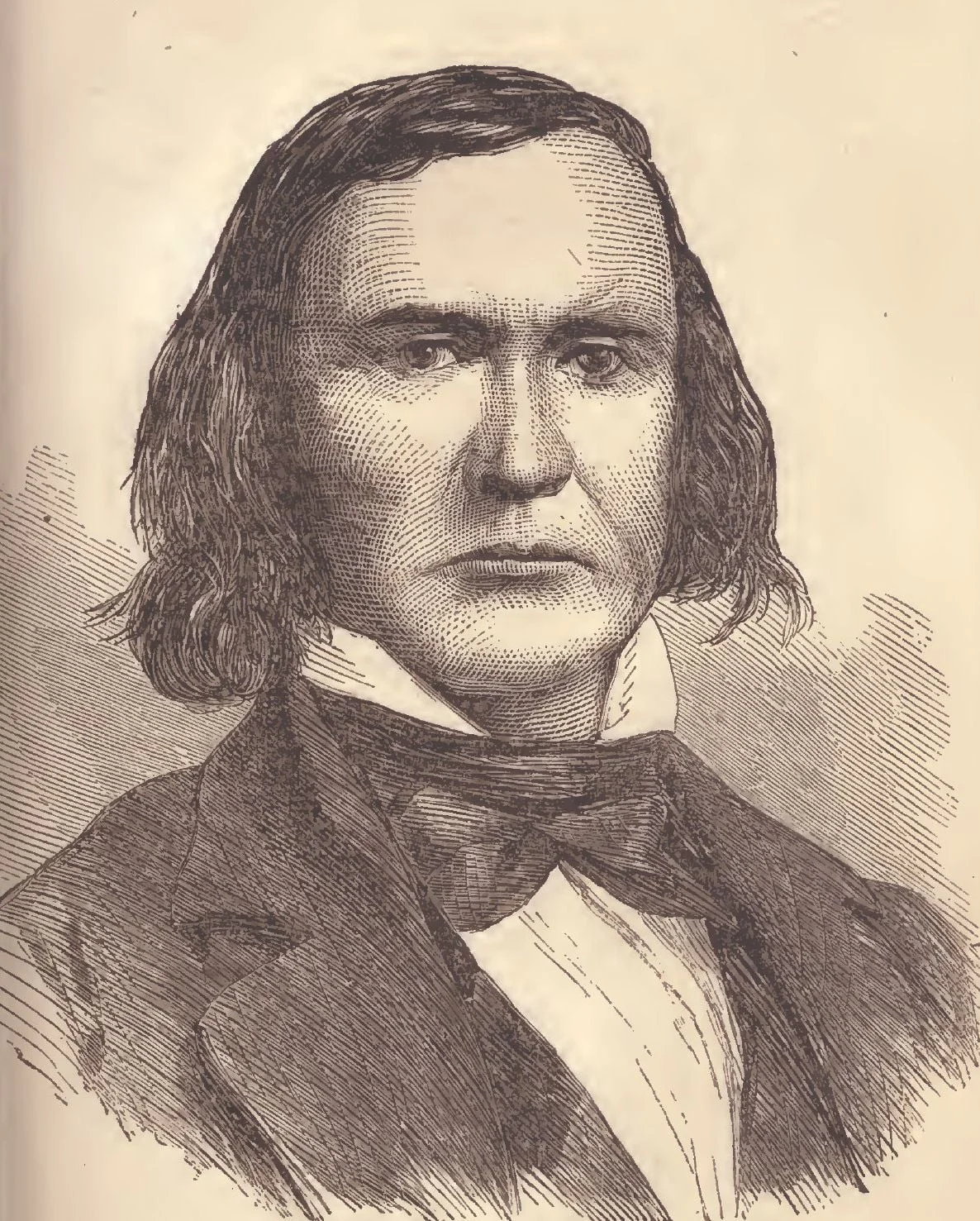

The subject of this sketch, Christopher “Kit” Carson, was born on the 24th of December, 1809, in Madison County, Kentucky. The following year his parents removed to Howard County, Missouri, then a vast prairie tract and still further away from the old settlements.

The new home was in the midst of a region filled with game, and inhabited by several predatory and hostile tribes of Indians, who regarded the whites as only to be respected for the value of their scalps.

The elder Carson at once endeavored to provide for the safety of his family, as far as possible, by the erection of that style of fortress then so common on the frontier, a log block house.

In this isolated spot, surrounded by dangers of every sort, the little Christopher imbibed that love of adventure and apparent disregard of personal peril, which made him so famous in after years.

When he was only twelve years old, being out one day assisting in the search of game, his father sent him to a little knoll, a short distance off, to see if a certain curious looking, overhanging cliff there might not possibly shelter a spring of water.

Instead of the spring, however, he found a shallow cave, and in it, sleeping quietly on their bed of moss and leaves, lay two young cubs. With boyish exultation he caught them in his arms and hastened as fast as possible toward his father.

In spite of their squirming he had borne them half way down the hill, when the sound of a heavy footfall and a fierce panting of breath warned him that he was pursued by the mother bear.

“Throw down the cubs,” shouted the father, but the boy either did not hear, or was determined not to obey, for he ran on.

Nearer and nearer he came, but faster gained the old grizzly behind him. The father held his rifle to his shoulder, ready to fire, but always between him and his foe, beat the brave heart of his boy. Another bound, and she would be upon him. Suddenly the boy turned still holding the cubs. Perhaps they saved his life. For instead of the terrible hug she might have given, the bear raised her huge paw and struck him on the shoulder. In an instant, boy, cubs and bear were rolling together on the ground, but as the bear came uppermost a bullet whistled through her neck, just below the ear, and with one pitiful moan she was dead.

One can easily imagine the pallor of excitement in the father’s face, giving place to the flush of joy, as he found his boy safe and unharmed, save by a wound from the bear’s claws. The youngster kept the cubs and tamed them, and years afterward, in telling the story of their capture, he would say, referring to the old bear: “She wasn’t no way a gentle play fellow, but she scratched her name on my right arm, and it hasn’t been rubbed out yet.”

Many similar incidents occurred in those early days’ when the boy accompanied his father and other back woodsmen in their hunting excursions, which gave him the hardihood and nerve which served him so well in after years.

When he was fifteen his father decided to give him the benefit of a trade, and, without any regard to his own inclination, young Christopher was apprenticed to a saddler. The weary monotony of stitching leather, and the close, sedentary nature of the employment, disgusted him. From the shop windows he could see the distant hills and woods where he had been wont to roam, and he longed for the free wild life, with all its perils, of a hunter and trapper.

He remained at his work, however, for two years, doing his duty faithfully, his only recreation being found in listening to the wild, fascinating stories of the scouts and guides who narrated their experiences with a vivid minuteness more attractive than any written story of “border fiction,”

At last the desire to lead a more active life became too strong for further restraint, and bidding farewell to the quiet pursuits of civilized life, he shouldered his rifle, donned the buckskin of the hunter, and at the age of seventeen, joined an expedition then on its way to Santa Fe.

On this expedition, the accidental discharge of a rifle shattered the arm of one of his companions, rendering amputation necessary. There being no surgeon accompanying the party, young Carson with a razor and an old saw cut off the limb, cauterizing the stump with an iron’ bolt heated red hot, but despite this un-skillful treatment, the victim recovered.

In the month of November, 1826, the party arrived safely at Santa Fe. Here they disbanded, and ”Kit” was left to his own resources. His first care was to acquire knowledge of the Spanish language as speedily as possible, for he found his English at a sad discount. He did not, however, tarry long at this ”mud house hole,” (as he quaintly termed it) but with his inseparable friend, the rifle, in hand, proceeded to Fernandez de Taso. Here he “hung up his pouch,” stopping at the house of an old hunter who many years before had quitted the “trail” to spend his old age in retirement.

Later in the spring of 1827 he joined an expedition on its way to Missouri. After this, being again idle, and as restless as ever, he hired himself to a party as a teamster “as a first-class M. D. (mule driver)” as he facetiously termed it.

Said he, in relating this episode in his history: “This was the hardest thing I ever undertook driving four mules hitched to one of those emigrant wagons. Mules always put me in mind of those half breed women on the plains if you coax them they’ll do as they please; if you try to make them do anything they won’t do it anyhow.”

His next venture was as a cook in the employ of Mr. Ewing Young at Taso in New Mexico, who was chief of a party of Beaver trappers. After many months spent upon the San Francisco and Salt Rivers, they proceeded to Sacramento Valley, where they suffered incredible hardships for want of food, being reduced at last to scanty rations of horseflesh. They were finally relieved by a party of the Mohave Tribe. After this they found their way westward to the Mission of St. Gabriel, a Roman Catholic Post; from here they pursued their course to San Fernando and from there to the Valley of the Sacramento.

In this wandering busy period of his earlier life, he acquired, young as he was, a reputation for skill in woodcraft and all the arts and mysteries of the trappers vocation, which compelled his associates, many of them older in years and experience than himself, to regard him as worthy their respect. Little did they think that while their names, with few exceptions, would be forgotten, or, to use their own expressive phrase, “wiped out,” that of Kit Carson would become historic.

As a marksman true to the renown of his native State, Kentucky he had no superior. “From a chipmunk to a redskin from a fish in the water to a pigeon on the wing,” his unerring “bead” never failed him. A glance of his eye along the barrel of his trusty weapon once raised for aim, boded sure death to the object. During these trips, too, he did not neglect improving himself in gaining an insight into the character and habits of the Indians. The tricks and devices of the “reds” soon became as an open book to him, and not a few of them learned to regard him as an individual whose scalp would be to them, if they could get it, as a trophy worth any effort to secure.

In several encounters with some of those roving remnants of tribes and bands of thieves, he evinced a sagacity, foresight, and originality in tactics in fighting them, which made him a particular mark for their vengeance. He wore his hair long so long that it reached to his shoulders and yet it was never “lifted.”

An incident soon occurred, which, although not fraught with the excitement of a real “scrimmage” with the Indians or Mexicans, fairly illustrates that sangfroid and coolness which was so marked a characteristic of Kit’s character. While he was with Young’s party some of the men, being under the influence of whiskey of the “kill on sight” kind, indulged in two or three quarrels with the Mexicans and Indians, which rendered it necessary for Kit and his companions to leave that region at once to avoid being overwhelmed by the immensely superior force which would be inevitably gathered to crush them.

Young, therefore, dispatched Carson ahead with a few men, promising to follow and overtake him at the earliest moment, and waiting another day; he managed to get his followers in a tolerably sober condition, and succeeded, though with much trouble, in getting away without the loss of a man, despite the desperate rage of the enemy, who were the more enraged at the loss of one of their number, who had been killed in a chance fray. In three days he overtook Carson, and they reached the Colorado in safety. Here, while left in charge of the camp, with only a few men, Kit found himself suddenly confronted by a band of Indians. They entered the camp with the utmost assurance, depending on their numbers. Carson at once suspected all was not right and soon discovered that despite their self-confidence each carried his weapons concealed beneath his garments. Carson, with the coolness for which he was proverbial, instantly ordered them out of the camp. Seeing the small number of the white men, the Indians declared they would not budge an inch. Carson‘s men stood around him, each with his rifle ready to be dropped to deadly aim at the first motion of their young commander. Carson addressed the old chief in Spanish (for the Indian had betrayed his knowledge of that language), and warned him, that although his (Carson‘s) men were few, they were ready for the emergency unless the camp was instantly vacated by the intruders. Carson‘s coolness and determination saved the camp and its effects.

Carson used to relate with quiet satisfaction, what he asserted was the most perilous he had ever “stumbled into.” It occurred during one of his tramps with Fitzpatrick, while trapping on the Larramie River. He had started from the camp alone, to shoot game for their evening meal, and had succeeded in bringing down an Elk, when two enormous grizzly bears suddenly came upon him so suddenly, that his rifle being unloaded, escape was impossible except by making with all speed for the nearest tree. He succeeded, with the bears just at his heels, but unfortunately dropped his rifle in his flight. He clambered up among the branches, and by a skillful maneuver, aided by his knife, managed to break off a large limb with which to defend himself.

“Those two varmints,” he said in telling the story, “actually surrounded the tree on all sides. I’d no sooner give one a settler in the face with the jagged end of the limb, than the other’d be scratching up on the off side. Twice they reached my feet, and one of ’em took a dose of boot heel that I should ha’ thought would make him despise the taste o’ shoe leather from that hour out. I wern’t noways lonesome that night. And I tell yer what, stranger, no man knows what it is to have his j’ints ache till he has tried the branch of a tree for a rocking chair some six or eight hours and a couple o’ friends socially inclined waiting for him down below. How did I get out of it? Well, I tell you how, patience will take a man out of most anything if he only has enough of it. I knew how ‘twould be.

“One of ’em trotted off home afore day light to ‘tend to her family, and I took solid comfort a goin’ down, knife in hand, and spiling the other one’s complexion.

“Taint no great shakes to kill a bar’, you know, but the wolves had picked the bones of that ere elk. That made me mad.”

While in the country of the Blackfeet Tribe, at the head of the Missouri, Carson received his first serious wound in a conflict with the “Red Skins.” According to Burdett‘s account, the Blackfeet had run off with eighteen of the trapper’s horses during the night, and Bat, with eleven men, started to recover them. After riding fifty miles upon the trail they came up with the marauders. The Indians asked for a parley, which Carson readily granted. The Indians informed them that they supposed they had been robbing the Snake Tribe, and did not desire to steal from the white men. Carson asked them why they did not lay down their arms and ask for a smoke. After some hesitation, the Indians laid aside their weapons, and prepared for a “smoke of peace.” After the Chief had made a non-committal speech, Carson came directly to the point, and said he would hear nothing more until the horses, all of them, were returned. The Indians then offered to return five of the worst horses. Carson and his party started at once for their guns, and, the Indians doing the same, the fight began.

After the first fierce encounter, the Indians took to the trees, and Carson‘s men were obliged to do the same.

It was here that a well aimed rifle ball crashed through Kit’s shoulder, shattering the bone. The wound was very painful and bled exceedingly, but in the midst of such a conflict there was no time to attend to it properly, and, though the fight ceased when night came on, they feared to light a fire, and so the torturing pain continued, unrelieved until morning. But his comrades say Kit uttered no word or moan of complaint, and raised himself on his well arm to add his voice to the shout of victory when the Indians were finally routed and the horses re-captured.

While employed as a scout and guide for Bent and Lieutenant Train, Kit fell in with an old Indian Chief, who, without being able to speak a word of English or Spanish, made the young hunter understand that he wanted whiskey, “fire water.”

Kit as usual, ready for barter, demanded skins, wampum, hatchets, anything that would be useful in future trading.

The Indian assured him, by signs, that if he would accompany him to his lodge in the wood he would pay him plenty.

Without fear or demur they went.

Arriving at the camp, the old brave proceeded at once to his own wigwam, and Kit saw through the open door a graceful girlish figure bending over the basket she was weaving.

He saw himself described by word and gesture to the girl, and saw her, as soon as she comprehended that he was a “pale face,” shrink away to the farthest corner of the lodge, and raise her dumb pleading eyes like a frightened doe at bay.

Kit Carson, though rude and uncultured, was not unkindly in his nature, and stalking at once into the wigwam, he shook his fist at the old chief, then patting the maiden on the head as he might have done to a pet kitten, said pleasantly: “No, no, my brown little beauty. You were not to be traded for a drink of whiskey. Wait here in peace while the eagle plumes are growing for your young warriors.”

The girl raised her beautiful eyes to the rugged smiling face so near her own, and, with one shy-confiding look, she put out her two hands and murmured some pleasant Indian word, which, though unintelligible in itself, was quite as eloquent in conveying her meaning as the straightforward reply which the poet Long-fellow puts in the mouth of the gentle Indian maiden, Minnehaha, in response to Hiawatha’s wooing: “I will go with you, my husband.” It is easy to imagine that, after so propitious an introduction, the wooing was not long and the wedding was soon celebrated. During the brief married life which followed, Kit and his brown bride seemed to have loved each other with a tenderness and sincerity quite unusual. But to the rudest cabin as to the palace home comes the death angel when least expected. And soon Kit was a widower, with one little daughter to care for.

It was this time that Carson left the wilderness and journeyed to St. Louis, in order to place his child under proper care.

And this journey proved a turning point in his life. For he then met for the first time Colonel J. C. Fremont, whose name even in that earlier stage of his honored career, had become “great in mouths of wisest censure.”While en route to St. Louis he passed a few days at the old “tramping ground,” where his boyish days had been passed. Although he found but few of the companions of his youth remaining there, still there was to him an intense satisfaction in the kindly greeting he received from the people to whom his name and exploits had become familiar.

Arriving at St. Louis, he unexpectedly found himself a hero, and the reception tendered to the greatest of hunters and scouts was almost equal to that usually vouchsafed the President.

In a few days he made all the necessary arrangements for the proper care and tuition of his daughter, and then prepared for his return to his old haunts. It was while thus engaged that he met Colonel John C. Fremont, who was then completing the details of his famous explorations in the Rocky Mountains, on the line of the Kansas and Great Platte Rivers. Colonel Fremont at once secured the services of “Kit” as one of his chief guides and assistants. On the 22d of May, 1842, the whole party started by steamer, and arriving at Choteau’s landing, on the Missouri River, they there encamped for a week before starting out upon their long and perilous expedition.

It was when they had reached the range of the Pawnees that Fremont recorded in his account of the expedition the eulogium upon “Kit.” “Mounted upon a fine horse, without a saddle, and scouring bareheaded over the prairies, Kit was one of the finest pictures of a horseman I had ever seen.”

On one occasion, just before entering the Sacramento Valley, “Kit,” was providentially the means of saving the life of Colonel Fremont, who, in his history of the expedition, relates the incident briefly:

“Axes and mauls were necessary today to make a road through the snow. Going ahead with Carson to reencounter the road, we reached in the afternoon the river which made the outlet of the Lake. Carson sprang dear over across a place where the stream was compressed among the rocks, but the parfleche sole of my moccasin glanced from the icy rock and precipitated me into the river. It was some few seconds before I could recover myself in the current and Carson jumped in after me, and we both had an icy bath. We tried to search a while for my gun, which had been lost in the fall, but the cold drove us out, and, making a large fire on the bank, we dried ourselves, and went back to meet the camp.”

In 1847, Colonel Fremont having been appointed Governor of California, “Kit” was dispatched to make the overland journey to Washington as a bearer of dispatches. His orders were to make the journey within sixty days. But, while following the trail leading toward Taos, having just entered a prairie, he met General Kearney‘s Expedition, sent out by the Government to operate in California. Being anxious to have the services of the renowned guide and hunter, he retained him and forwarded the dispatches by Mr. Fitzpatrick.

Of this Expedition he was at once the guide and trusted counselor. Through perils and difficulties, which only could befall an expedition of this character, traversing great tracts of prairies and forest crossing the great chain of mountains through snow and storm, and overcoming impediments which, at times, seemed almost insurmountable it was to Carson that the General turned for advice and assistance, and history records how faithfully and with what self-sacrifice the great hunter executed his task.

After this duty had been fulfilled, and a short rest taken at the destination of the command, Carson wended his way once more toward Taos, in the vicinity of which he had determined to make himself a home.

He finally fixed upon a Valley, the Indian name of which is “Rayedo,” one of the most magnificent spots in the region, Fertile, well watered by a broad, sweeping stream, and in the immediate vicinity of his old trapping and hunting companion, Maxwell, the “settlement” thus established seemed a paradise of rest and comfort to the wearied men, whose toil had wrought so much good to those they served.

He received the title of Colonel, by which he was known through the later years of his life. He commanded the Expedition and operation from Fort Canby, the objective point being Canon de Chelly in New Mexico, and had at his disposal four hundred men, of whom only twenty-five were mounted. Taking the road via Pueblo, Colorado, he started for the Canon. He achieved successfully the whole object of the Expedition, and received the thanks nobly earned of the Government and the unqualified admiration of that portion of the then new country, to which he had by his efforts secured a lasting peace from the molestations of the Indians.

When the war of the rebellion closed, Carson continued in the employ of the Government until April, 1868, when he was, while at Fort Lyon, Colorado, suddenly taken ill with an aneurism of an artery in the neck. He died a comparatively painless death. He had but just returned from a trip to Washington; whither he had gone in company with a deputation of Indians upon matters connected with a Treaty. On his way back, he visited, by special invitation, New York, Philadelphia, Boston and other cities, where he was received with the honor his services and great fame so well deserved.

Upon his death, he bequeathed the rifle, which in all his trips and expeditions for the previous thirty-five years he had carried, to Montezuma Lodge, A. F. and A. M., at Santa Fe, of which he had long been a member. His daughter, now married, is still a resident of St. Louis.

There, almost within the shadow of the mountains he had so often explored, where he had trapped and hunted and given battle to the red men, passed away one who has not been inaptly termed by Burdett, “The Monarch of the Prairies,” leaving none behind to claim his throne as an equal in all that constitutes the pioneer, guide, soldier, trapper and hunter. Unlettered, with no friends but his own indomitable courage and his trusty rifle, he toiled through life serving others rather than himself and with an unselfish devotion to his profession. At last, and scarcely in the modesty of his nature claiming it, he won for himself an honored place in history and in the affectionate remembrance of his countrymen and friends.