The line established between the Sioux and the Chippewa by the treaty of 1825 ran in a south-easterly direction across what is now the State of Minnesota, from a point near where Fargo now stands, crossing the Mississippi River at St. Cloud. Below this line were the four bands of the Eastern division of the Sioux. With the exception of a tract set apart for Fort Snelling by treaty made with Lieutenant Pike, there was until 1837 no authority for white settlement within the region. Yet settlers had come; at first the French traders, later Americans from the east. By 1849 the population was deemed sufficient to justify the organization of a Territorial Government; but their first census mustered fewer than five thousand non-Indians with the extent of the Territory. The general estimate of the numbers of the Sioux within the same section was then about eight thousand.

Apparently the first function and possibly even the purpose of establishment of this Territory was the negotiation of a treaty which should extinguish the Indian title to as large a portion of the land as possible. During two or three years of parleying, it became apparent that back of the Indians’ desire for a treaty lay the power of the trader and the half-breed. Lewis and Clark had found the trader at the mercy of the wild Indian tribes, hampered by a system of “credits” by which the superior numbers of the natives enabled them to help themselves to the entire remaining store of the dealer at the close of a hunting season, under promise to bring him furs and peltries by way of recompense the following spring. So long as the Indian was more powerful these debts did not disturb him; and if next year he failed to produce the skins, or bartered them to some other trader whose goods were more attractive, there was little recourse.

But with the treaties that brought the Indian money and the trader the possibility of cash payment, the situation changed. The merchants, with the half-breeds who were their friends and interpreters, and in very many cases their sons and relatives, were enabled to wield a power in Indian councils. And in the making of a treaty they could and did insist upon cash payments that would permit the Indians to “comply with their engagements.” In other words, the United States assured the payment of the trader’s accounts. In dealing with the lands of the tribe as a whole the nation was called upon also to bind itself to pay the debts of individual Indians.

It was this situation which led to the cession of a half-breed tract in the treaty of 1830. The hopes of profit through the sale of this land and the timber upon it were defeated by the fact that, contrary to the expectation of the beneficiaries, the cession was decided to convey only the same title as the given to other Indians by treaty in their reservations; and this did not include the right to alienate their land. So the expectation of realizing goodly sums through the sale of tracts of land was defeated.

The evils inherent in this state of affairs, whereby the Indians and the United States were both forced to rely upon the assistance of a body of men whose interests were antagonistic to both, are only too clear. In order to dispose of the land and secure the annuities which he coveted, the Indian must promise a reward to the traders and their adherents. In order to secure the consent of the Indians to land cessions, the United States must carry on its negotiations through the men on the ground, who held the Indians in fealty by ties of blood, language, debt and daily dependence. One need not wonder that most Indian treaties afforded scandal and abuse.

The treaties of 1821 did more than that. They led directly to the outbreaks of ten years later. But their immediate result was the removal of the Sioux tribes of Minnesota to a reservation which was a strip twenty miles wide along the valley of the Minnesota River, from the Yellow Medicine River to the shores of Lake Traverse. In return for the cession of the remainder of the territory up to the Chippewa line the Sioux Indians were to receive cash, annuity payments of $68,000 for fifty years, and other appropriations, the whole amounting to $1,665,000. This included an allowance of $210,000 to enable them to “settle their affairs and comply with existing engagements.” It is not difficult to see where the traders were to reap their harvest.

White population began to pour in; from the 4,800 of 1849 the numbers grew to a hundred thousand in 1856. The land-hungry white man learned quickly what abundant harvest this fresh soil would bear. Meanwhile the Indian, on his narrow reservation, nursed his resentment and awaited an opportunity to gratify it by action.

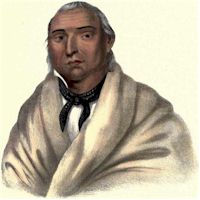

Sparrowhawk that comes to you walking

A Sioux Chief

Little Crow was a chief of the Kaposia division of the Mdewakanton Sioux. His Indian name is affixed to the treaty which ceded the Minnesota lands; but he lost no opportunity of fostering dissatisfaction with the results of the treaty among the warriors of his tribe. Toward the white man, however, he maintained an apparent friendliness. He was accounted a force for temperance, an adherent of the missionary who had, indeed, been sent to his village at his request. Under this pacific cloak he remained the hostile,” and in 1862 led his people into a war that spared neither man, woman nor child.

To the south and east of the nation was in the grip of a deadly war and rumors of battles in which the southern forces were victor were eagerly passed around in the Indian camps and villages. The time for the annuity payment came and passed with the distribution of accustomed thousands. The feeling that the Government was going to be unable to pay gained strength. And did not the traders show their belief in the failure of the Government, by refusing further credit? More and more the able-bodied men are being withdrawn from the white settlements, from the agencies themselves. Clearly it was time to shake off the yoke of the oppressor.

Little Crow had made careful plans and was waiting for allies from other Sioux bands. But the precipitance of some of his young men brought the matter to a head sooner than he had designed. Four young braves started out to murder families of settlers and pillage their homes on the very day, August 15, 1862, when the diplomatic Little Crow was consulting with the agent about a new brick house which the Government was to build for him at his request. On Sunday morning Little Crow attended the services at the Episcopal mission; that very afternoon the slaughter began. Learning of it at daybreak the next morning, Little Crow and the chiefs of the tribe realized that they must give up the young men for the ignominy of trial and punishment, or declare the warfare general. The decision of the astute leader was for war.

“It must come,” he said, “Now is as good a time as any. I am with you. Let us kill the traders and divide their goods.”

By seven in the morning two hundred painted warriors surrounded the agency and at a signal opened fire, killing five white men at once and wounding many others. The “Minnesota Massacre” had begun. The official report reads:

“And now followed a series of cruel murders, characterized by every species of atrocity and barbarity known to Indian warfare. Neither sex, age nor condition were spared. It is estimated that from eight hundred to one thousand quiet, inoffensive and unarmed settlers fell victims to savage fury are the bloody work of death was stayed. The thriving town of New Ulm, containing from fifteen hundred to two thousand inhabitants, was almost destroyed. Fort Ridgely was attacked and closely besieged for several days, and was only saved by the most heroic and unfaltering bravery on the part of its little band of defenders until it was relieved by troops raised, armed and sent forward to their relief.

“Meantime the utmost consternation and alarm prevailed throughout the entire community. Thousands of happy homes were abandoned, the whole frontier was given up to be plundered and burned by the remorseless savage, and every avenue leading to the more densely populated portions of the state of crowded with the now homeless and impoverished fugitives.”

And while the savages were surrounding Fort Ridgely, within its wall were the sacks of gold with which the annuity payments were to be made. Delayed through the tardiness of Congress in passing the usual appropriation bill, the shipment had reached the fort on August 18, the very day when Little Crow made his decision. A day or two earlier, and the history of that harvest season might have read very differently.

Relentless hostilities raged for more that n month. The few soldiers sent at first proved inadequate to control the situation. The Indians crossed the Minnesota border and attacked Fort Abercrombie in Dakota. Finally the white man mustered sufficient force to meet the emergency; and in a battle at Wood Lake, Minnesota, on September 22, Little Crow and his forces met defeat. Five hundred Indians were taken prisoner. The chief himself, with some of his braves, fled for shelter to the Yankton Sioux in Dakota.

Depredations did not entirely cease. Little Crow, the following year, was killed by a settler who was defending his home. The old chief was not without a successor to carry on his work. His six wives had borne him twenty two children, so Little Crow the Younger succeeded to command.

The Army court-martialed some three hundred of the Indian braves captured at Wood Lake and sentenced them to be hanged. President Lincoln’s clemency reduced the number to thirty-eight, who met their fate on one scaffold on February 26, 1863. The remainder, whose sentence had been commuted, were confined for a year on an island down the Mississippi.

But the real sequel of the uprising was the driving of all the Sioux, hostile or friendly, from the borders of Minnesota. Public feeling had risen too high, public fear was too acute, to permit them to remain. “The Indians must be sent out and kept out of the State, or for years and years to come there can be no peace or security,” wrote Thomas Galbraith, who was the agent for Little Crow‘s band.

In the summer of 1863 the Santee Sioux and the Winnebago Indians of Minnesota, the latter quite innocent of the uprising but forced to share in its consequences, were removed by the military to Crow Creek agency, about a hundred and fifty miles north of Yankton, on the Missouri River. This removal was attended by cruelties that later led to a congressional investigation. Many of the hostile Sioux made their escape to Canada, which as years went on became more and more a refuge for enemy bands.

The Sioux to the West were no less turbulent during this time; but they had no large body of settlers upon whom to wreak their vengeance; and they lived in a country so vast that they could scarcely be brought to account for their depredations. Passing parties of emigrants felt their enmity, however, and travel across the plains lost whatever vestige of security it might once have possessed. The seven Sioux tribes of the Upper Missouri declared general war and death to all whites in 1863; pursued by General Sully, they retreated toward the Yellowstone, burning the prairies as they went, and thus effectively cutting off the pursuit.

So the story went; an unceasing record of depredations and retaliations, of attacks and retreats. With the close of the Civil War, a large body of white men trained in fighting were available for the troubles in the West. The year 1865 witnessed the making of nine treaties with nine different bands of Sioux, and the general war of the Indian tribes was thought to be over. Hostilities of one sort or another, however, were to last a full decade longer. One chapter had closed; but another began almost at once.