Three miles northeast of Muskogee the Verdigris and Grand rivers half a mile apart, discharge their waters into the Arkansas, which thus augmented, flows in a southeasterly direction to the Mississippi, six hundred miles distant by the course of the stream. This junction of the three rivers, establishing the head of navigation, became known in early times as the Three Forks, or more commonly, as the mouth of the Verdigris. In the days when river navigation played such a tremendously important part in the life of this western country, the mouth of the Verdigris maintained for many years an importance that long since has passed away and been forgotten. As a trading center and theater of military and more peaceful operations in the winning of this country, it was second to none west of the Mississippi.

From the mouth of the Verdigris, in its day the farthest thrust of the pioneer, the conquest of a large part of the Southwest was achieved. The story of this campaign covering a period of nearly fifty years, has never been written, though it contains much of romance that even in the form of isolated or related incidents, it is possible to record. The Louisiana Purchase itself was romance. In 1803 President Jefferson directed Monroe and Livingston to negotiate for the purchase of New Orleans for the United States, and they brought home title to an empire, practically a donation from France.

From the day in April, 1682, when La Salle stood at the mouth of the Mississippi and proclaimed the great western country drained by that river to belong to France, until 1762, when she ceded it to Spain, France made no adequate effort to utilize or even to explore that great empire. The earliest explorers of the southwest were Spaniards. The first known visitors were De Soto who crossed the Mississippi in 1540, and Coronado who came from the south the next year. Schoolcraft traces the march of De Soto to the mouth of the Verdigris. He says 1 that after De Soto crossed the Mississippi with his army “he passed an uninhabited region for five days, west, over the remaining elevations of the Ozark chain, and came to fertile prairies beyond, inhabited by Indians called Quipana, Pani, or Pawnee. A few days’ further march brought him to the banks of the Arkansas, near the Neosho, which appears to have been about the present site of Fort Gibson. Here, in a fruitful country of meadows, he wintered. Next spring he marched down the north banks of the Arkansas, to a point opposite the present Fort Smith, where he crossed in a boat, previously prepared. He then descended the south bank of the river to Anilco (Little Rock), where the army crossed to the north bank, partly on rafts, and reached the mouth of the Arkansas where he died.” It was within the next year that Coronado entered the western part of Oklahoma from the southwest and proceeded to a point within what is now Kansas. 2

The limits of the Spanish and French dominions were not clearly defined and between them there was a vast expanse of unknown country over which the Indians hunted and fought for supremacy that afterward became the American Southwest. While both nations had contributed to the nomenclature of the natural features of this region and thus recorded the transient presence of their trappers and traders, neither built any settlements upon it. On the eastern fringe, along the Mississippi the French had established Arkansas Post, 3 destined to figure in the history of the southwest and pass away; Sainte Genevieve, Saint Charles, Saint Louis and other early settlements. On the south and west the Spaniards were found at Natchitoches and San Antonio de Bexar, Santa Fe and Taos and along ancient Spanish trails that connected them.

Desultory efforts at exploration and conquest of this great region were made by both nations. The French Government issued a patent to Antoine de Crozat in 1712, granting him “the commerce of the country of Louisiana.” After five years, despairing of anything to be gained by its possession, de Crozat surrendered his patent and abandoned his colony. The same year a grant was made by the French Government to John Law, of the Mississippi Commerce Company, to be exploited in the ill-fated Mississippi Bubble. The Mississippi Company undertook to establish barrier settlements to maintain the territorial claims of France and to arrest the progress of the Spaniards. Bernard de la Harpe in 1719 with a body of troops ascended Red River to the Caddo villages where he built a fort called Saint Louis de Carlorette on the right bank of that river. He then pursued his discoveries to the Arkansas River where he visited an Indian village three miles in extent, containing upwards of four thousand persons. It was situated about one hundred twenty miles southwest of the Osage.

The Louisiana Purchase

Early in the eighteenth century the French ascended the Arkansas to its source and for nearly eighty years navigated that river, the Canadian and other tributaries as far as the Spanish possessions in the pursuit of trade and furs. At an early day a company of French traders ascended Arkansas River and established a trading post in the mountains south of the headwaters of that stream. There they trafficked with the Indians and with the Spaniards of Mexico until the Spanish merchants of Santa Fe feeling the stress of competition, procured their imprisonment and seizure of their effects on the charge that the Frenchmen were trespassing on Spanish territory. Ultimately however it was decided at Havana that they were within the boundaries of Louisiana and the prisoners were released and their goods restored to them.

At the same time the Spaniards were making similar ventures from the west across this unknown land. A company under Captain Villasur left Santa Fe in 1719 and marched northeast in quest of the Pawnee villages, but lost their way and unluckily arrived among the Missouri, whose destruction they meditated. Ignorant of their mistake as the latter spoke the Pawnee language, they disclosed their plans without reserve and requested the cooperation of the Missouri. The latter attacked the Spaniards in the night while they slept in fancied security and killed all of them except the priest who escaped on his horse. 4 The boldness of the Spaniards in penetrating six hundred miles from Santa Fe into an unknown country apprised the French of their danger. The latter therefore dispatched De Burgmont with a considerable force who took possession of an island in the Missouri River some distance above the Osage on which he built Fort Orleans. 5

Finally wearying of the ownership of a territory that had occasioned great trouble and expense and offered little hope of profit, and that exposed her to costly reprisals at the hands of England, France ceded to Spain that part of Louisiana lying west of the Mississippi. During the thirty-eight years that Spain owned Louisiana, frequent irritations arose between Spain and the American Colonies over the use of the Mississippi River through Spanish territory. On October 1, 1800, Spain secretly ceded Louisiana back to France so that the United States did not hear of it for nearly two years; but, learning of the transaction in which we had such deep concern, American indignation manifested itself by threats of war against France and negotiations were opened with the latter which led to the purchase of Louisiana by the United States. In 1803, again to rid France of the territory she was unable to use and to prevent England taking it from her, Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States for less than fifteen million dollars, a sum that is returned in a few days to the owners of oil wells in that territory.

In contrast with the futile policy, or lack of policy, of France and Spain, were the vigorous steps at once inaugurated by the United States, in spite of short-sighted opposition of members of Congress, many of whom opposed the ratification of the purchase of Louisiana on the ground that it was so remote from the populated part of the United States that its possession threatened dismemberment of the Union by the setting up of another government in the West. Even before the Louisiana Purchase was consummated, Thomas Jefferson was planning an inquiry into the extent and character of that great region, and the next year after the purchase was made his plans were so far matured that he was able to send Captain Meriwether Lewis and Captain William Clark on their memorable voyage up the Missouri River in the performance of an achievement without parallel in the history of our country.

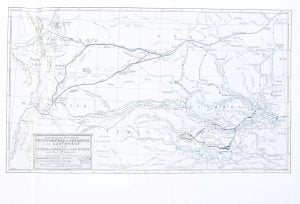

The Louisiana Purchase was served by four great natural highways; the Mississippi, Missouri, Arkansas, and Red rivers, that at once lent themselves to the scheme of exploration launched by Jefferson.

Early American Explorations

Before Lewis and Clark returned from their expedition, Lieutenant Zebulon M. Pike 6 had ascended to the headwaters of the Mississippi to explore and report on that region of newly acquired territory, which he accomplished in eight months and twenty days. The next year, in 1806, Pike was sent on an expedition to explore the headwaters of the Arkansas, with directions to travel south from that region to the headwaters of Red River and, returning down that stream, to report on the southwestern boundary of our purchase.

Relations between Spain and the United States were then serious, and the troops of the two governments came near hostilities on the frontiers of Texas and the Orleans territory. News of Pike’s preparation was conveyed to Nacogdoches and from there to Chihuahua. The Spaniards then ordered out an expedition to halt the American explorers and to explore the country between New Mexico and the Missouri.

From Santa Fe the Spanish invasion departed under the command of Lieutenant Don Facundo Malgares. It consisted of six hundred mounted troops with over two thousand horses and mules carrying ammunition and supplies for six months. They descended Red River two hundred thirty-three leagues, where they held a council with the Comanche Indians, then struck off northeast to the Arkansas where Lieutenant Malgares left two hundred forty of his men with the lame and tired horses, while he proceeded to the Pawnee republic. Here he was met by the chiefs and warriors of the Grand Pawnee with whom he held councils and presented them with medals and flags in token of Spanish sovereignty. Malagres took as prisoners all the American traders he found among the Indians.

Pike soon afterward visited the Pawnee villages and induced the chiefs to take down the Spanish flags and substitute those of the United States. 7 He then proceeded up the Arkansas and was successful in gaining the sources and then departed southward upon what was unquestionably Spanish territory now within the limits of southern Colorado; here he was taken prisoner by the Spaniards and carried to Santa Fe and under the command of Lieutenant Malgares he was conveyed from Santa Fe to Chihuahua; his papers were seized and he was taken to Natchitoches where he was released July 1, 1807.

Under Pike’s command upon this expedition was James B. Wilkinson, 8 first-lieutenant of the Second Regiment of Infantry, who separated from Pike on the upper reaches of the Arkansas River within the present limits of Kansas, and under orders of his chief descended that river to its mouth. Wilkinson had five men with him, and at the beginning of their descent they cut a small Cottonwood tree from which they fashioned a canoe with great difficulty; this being insufficient, they formed a second with four buffalo skins and two elk skins; this held three men beside himself and one Osage. In his wooden canoe were one soldier, one Osage and their baggage. One other soldier walked along the shore.

From their departure on the twenty-seventh of October, their journey was a succession of discouraging difficulties and hardships, occasioned by the cold, rain, and snow, and frequent lack of food. On December 27, they passed the mouths of the Verdigris and Grand rivers, where Wilkinson first noted the quantities of cane with which the fertile river bottom was covered beyond that point. Two days later they passed the falls now known as Webbers Falls, near the mouth of the Canadian, then “a fall of nearly seven feet perpendicular”, and now only a ripple over submerged rocks.

Lieutenant Wilkinson reached Arkansas Post January 9 and New Orleans March 1; immediately thereafter another expedition was planned to explore the Arkansas River from the mouth to its source and the country beyond. It was in charge of William Dunbar and Thomas Freeman and was to be accompanied by an escort of thirty-five men under the command of Lieutenant Wilkinson assisted by Lieutenant Thomas A. Smith. May 20, 1807, General Wilkinson at New Orleans wrote to Captain Pike, 9 then about to reach Natchitoches at the end of his captivity in Mexico. He told Pike that the exploring party was then in motion on the Arkansas and the escort in two boats would reach Natchez in a week or ten days, and would then proceed with all possible dispatch. Pike was directed to send to the exploring party on the Arkansas all the information gained by him which he thought essential to the enterprise. General Wilkinson added that the party expected to camp for the winter near the Arkansas Osage at the mouth of the Verdigris. However, as appears from Pike’s letter 10 of July 5, 1807, the expedition was suspended for reasons which he does not disclose; but one may assume that further exploration in the west was embarrassed by the charges freely made that Wilkinson’s orders to Pike to explore Arkansas and Red rivers were but a subterfuge for carrying into effect Wilkinson’s share of the conspiracy he was charged with having entered into with Aaron Burr for the conquest and exploitation of the Spanish Southwest.

President Jefferson laid before Congress February 19, 1806, the interesting report of Lewis and Clark and of Doctor John Sibley on his travels up Red River as high as the Ouichita, now in Arkansas, in 1803-1804 11 and a report of a Red River expedition in 1804 by Dunbar and his exploration of the hot springs, now in that state. 12

A second expedition was undertaken in 1806 by Thomas Freeman, Captain Sparks, Lieutenant Humphrey, and Doctor Custis and a force of twenty-four men in two flat-bottomed barges and a pirogue. They passed the Great Raft with difficulty, but were arrested and driven back by the Spaniards after they had ascended Red River six hundred miles. 13 Doctor Sibley furnished a report 14 made to him by his assistant, a Frenchman named Francis Grappe, concerning a trip he made in 1803 up Red River from Natchitoches to Washita River now in the Chickasaw Nation.

When the cession of Louisiana was made, the ceded territory was at first divided into two parts. The district on the west bank of the Mississippi, lying south of latitude thirty-three, or what is now the state of Louisiana, was called the territory of Orleans; and the remaining portion, comprising a vast and unknown extent of country between the Mississippi and the Pacific Ocean was at the same time constituted the district of Louisiana and placed under the government of Indiana Territory. In March, 1805, it was denominated the territory of Louisiana.

The district of Louisiana under the same boundaries in 1812 was constituted a territorial government under the name of the territory of Missouri, which remained so until March, 1819, when the southern part of the territory was cut off and from it was created the territory of “Arkansaw.” Arkansaw Territory extended from the Mississippi River westward to the Spanish possessions and was about six hundred miles long, including approximately the present area of Arkansas and Oklahoma.

Choteau Family’s Influence on the Osage

At the time of the Louisiana Purchase there had begun the growth of the influence of the family of Chouteau which was destined to affect profoundly the development of this southwestern country. Auguste Chouteau and Pierre Chouteau 15 were half-brothers who came to Saint Louis from New Orleans. Pierre Chouteau who was born in New Orleans and arrived in Saint Louis in 1764, was the father of Colonel A. P. Chouteau born in 1786, Pierre Chouteau Jr. born 1789, Paul Ligueste Chouteau born 1792, and a number of other sons. Pierre Chouteau was engaged in the fur trade out of Saint Louis in the early days, operating largely on the Missouri River For twenty years he had traded with the Osage Indians who lived on the Missouri in the western part of the present limits of the state of that name. Manuel Lisa, 16 a Spanish trader of Saint Louis, and other traders in 1802 secured from the authorities then in power the exclusive license to trade with the Osage Indians, 17 and thereby deprived Pierre Chouteau of this business. Chouteau was resourceful, and having great influence with the Osage, induced half of that tribe, or nearly three thousand individuals, to remove from the Missouri River to the vicinity of the Three Forks, or the mouth of the Verdigris River, which was the head of navigation, and offered the best facilities for shipping supplies to the Indians and for carrying furs from the Indian country to markets in Saint Louis and New Orleans. The presence of large salt springs in the vicinity was an added inducement to settlement there. Chouteau had selected for chief of this portion of the tribe an influential Osage named Cashesegra, or Big Track; but while he was the nominal head, Clermont, also known as the Builder of Towns, was the greatest warrior and leader, and their principal town on the Verdigris was called Clermont’s or Clermo’s Town. 18

President Jefferson, in February 1806, submitted to Congress a statistical report made to him by Captain Meriwether Lewis in 1805, concerning the Indians west of the Mississippi. Speaking of the Osage, Captain Lewis said: 19

“About three years since, nearly one-half of this nation, headed by their chief, Big Track, emigrated to the three forks of the Arkansas, near which, and on its north side, they established a village, where they now reside.”

Answering the President’s inquiry as to the place where it would be mutually advantageous to set up a trading establishment with these Indians, Captain Lewis designated the Three Forks of Arkansas River In the account of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, they record that on May 31, 1804, they were encamped near the mouth of the Osage River, not far from where Jefferson City, Missouri, now is: 20

“. . . In the afternoon a boat came down from the Grand Osage river, bringing a letter from a person sent to the Osage nation on the Arkansas river, which mentioned that the letter announcing the cession of Louisiana was committed to the flames – that the Indians would not believe that the Americans were owners of that country, and disregarded St. Louis and its supplies.”

The incident of Pierre Chouteau bringing the Osage down to the mouth of the Verdigris was mentioned by Lieutenant Wilkinson and by Major Pike 21 in their accounts of their explorations of the Arkansas River in 1806, and by Major Stephen H. Long in 1820.

The great influence of Chouteau with the Osage and his enterprise in leading two or three thousand of this tribe from their old home to the mouth of the Verdigris where they established themselves convenient to navigation; and the resultant location of a trading post, a mission, an army post, and Indian agencies in the neighborhood, affected enormously the importance and development of that vicinity and its influence over the surrounding country. And the name of Chouteau, now scarcely remembered in the annals of the Southwest, was probably more potent in the destinies of that section of country than any other. It will be seen that the Three Forks was planned by nature, and was early recognized and selected by white explorers as the focal point for enterprise in the midst of a vast extent of unexplored country, which was in time to extend its influence to the winning of the great Southwest. President Jefferson’s message at this early day introduced the vital element of transportation into the destiny of that country, and fixed upon a point and route that survived in that employment until the coming of the railroad.

The Cherokees and the Osage

In the first message of President Jefferson after the Louisiana Purchase, he committed the administration to the policy of confirming to the Indian inhabitants of that country, their right of occupancy and self government, to establishing friendly and commercial relations with them, and to ascertaining the geography of the country acquired. It soon became a favorite policy with the government to present to Indians living east of the Mississippi the advantages of moving westward to the Louisiana Purchase; and within the first few years after that acquisition many treaties were entered into with eastern tribes providing for their removal.

A delegation of Cherokee chiefs in May, 1808, requested President Jefferson to permit part of the tribe to remove west of the Mississippi where they could pursue the lives of hunters. The President gave the necessary permission but in order to effect the desired removal it was necessary to acquire the title to the land from the Osage Indians who claimed dominion over the country west of the Mississippi between the Arkansas and Missouri rivers where the Cherokee wished to locate. This was accomplished by treaty entered into at Saint Louis in 1808 and 1809. 22

While this treaty was not ratified until April 28, 1810, President Jefferson on January 9, 1809, authorized the Cherokee to send exploring parties to the country ceded by the Osage to examine that on the waters of the White and Arkansas rivers. The report of the explorers being favorable, emigrating parties were soon on the march to Arkansas with the active assistance of government; and within a few years there were several thousand Cherokee living in the vicinity of White and Arkansas rivers.

William L. Lovely, 23 who had been serving as assistant to Colonel Return J. Meigs, Cherokee Indian Agent in Tennessee, was directed in 1813 to take up his station with the Cherokee in Arkansas. Directly upon his arrival he reported 24 to Governor Clark. He complained bitterly of the havoc wrought by white people on the game of the country which belonged to the Indians. He said that they killed the buffalo in great numbers for the tallow, and left to decay the carcasses that might have sustained the Indians. Bears were killed in the same ruthless manner for the oil they yielded.

Lovely wrote 25 to his friend Colonel Meigs, May 29, 1 815:

“. . . You will perceive amongst the papers enclosed to you for the Secretary of War, a copy of a letter from some gentlemen to whom I have given positive permission to establish a salt work near the Osage village. A work of this kind is essentially necessary to the good of the Indians and others of this country, having to give $30.00 often per barrel. I wish you therefore to write to Governor Clark and the Secretary of War on the subject.”

In all probability this was the famous salt works near which Union Mission was located.

Lovely reported 26 to Governor Clark in 1816 that robberies and murders committed by the Osage were about to force the Cherokee to war. He secured the attendance of the chiefs of Clermont’s band in July 1816, at the mouth of the Verdigris, 27 where he attempted to adjust the difficulties of the Osage with the Cherokee and whites. Lovely proposed to the Osage that the government would pay all claims held against them by the Cherokee and white people for robberies and other depredations, if the Osage would relinquish to the United States the great tract of land lying on the north side of Arkansas River, bounded on the west by the falls of the Verdigris and on the north by a line running thence to the upper saline on Six Bull (Grand) River, and from there east to White River and the Cherokee settlements. This proposition was assented to by the Osage and their agreement was signed July 9, 1816, by Clermont and other Osage chiefs. 28 This great tract of over seven million acres became known as Lovely’s Purchase, and was later the subject of acrimonious contention between the people of Arkansas and the Cherokee Indians.

But the apparent adjustment between the tribes was only temporary. In August 1817, Tallantusky and other Cherokee chiefs in the west wrote to Governor Clark 29 that for nine years they had been trying to make friends with the Osage, but to no purpose; that they had been trying to raise crops for their families but the Osage had stolen all their horses so that they were reduced to working the land with their bare hands; they had promised the President not to spill the blood of the Osage if they could help it, but that now the rivers were running with the blood of the Cherokee, they had determined to proceed against their enemies.

The news came from Saint Louis 30 that a “formidable coalition had been effected consisting of Cherokee, Choctaw, Shawnee, and Delaware from east of the Mississippi, and Caddoes, Coshatte, Tankawa, Comanche, and Cherokee west, for a combined assault on the Osage. The Coshatte, Tankawa, and Caddoes on Red River and the Cherokees of the Arkansas complained that the Osage were perpetually sending strong war parties into their country, killing small hunting bands of their people and driving off their horses.” The report came from a man from New Orleans who said that he traveled part of the distance between Ouichita and Arkansas rivers with a large party going to join the confederate troops who had with them six field pieces with several whites and half breeds who learned the use of artillery under General Jackson during the recent war.

While this account of the preparations for battle was probably overdrawn, the contemplated attack was actually made by a large force. Say’s report of Captain Bell’s exploration of Arkansas River contains an account of the engagement that ensued when the invading army reached Clermont’s town. 31 He says the attacking force amounted to six hundred and included Cherokee, Delaware, Shawnee, Quapaw, and eleven white men. They sent word to the Osage that they were a small party of chiefs and old men coming to discuss peace with them, and requested Clermont to meet them at an appointed place near their town. Clermont was away from home with the warriors of the band on a hunting expedition, and an old man was appointed to act in his stead. On his arrival at the proposed council ground the Osage found himself surrounded by hostile forces who immediately killed him. The design of this act of perfidy, says Say, was to effect the destruction of Clermont, the bravest and most powerful of the Osage. The invaders then attacked the defenseless town in which remained only old men, women, and children, who offered but little resistance. A scene of outrage and bloodshed ensued, in which the eleven white men were said to have acted a conspicuous part. They fired the village, destroyed the corn and other provisions of which the Osage had raised a plentiful crop, killed and took prisoners fifty or sixty of the inhabitants. In Nuttall’s more highly colored account he says: 32

“The Cherokees, now forgetting the claims of civilization, fell upon the old and decrepit, upon the women and innocent children, and by their own account destroyed not less than 90 individuals, and carried away a number of prisoners. A white man who accompanied them (named Chisholm), with a diabolical cruelty that ought to have been punished with death, dashed out the brains of a helpless infant, torn from the arms of its butchered mother. Satiated with a horrid vengeance, the Cherokees returned with exultation to bear the tidings of their own infamy and atrocity.”

Citations:

- Schoolcraft, Henry R., LL.D. Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, vol. iii p. 50[

]

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe. Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of the North Mexican States, vol. xv, 85.[

]

- “Arkansas Post perpetuates the name of the oldest establishment of whites in the lower Mississippi valley. The present village is on the N. bank of the Arkansaw River, in the county and State of Arkansas, 73 m. S.E. of Little Rock, the capital. Though never a locality of much importance, its place in history is secure and permanent. Early in the year 1685, Henri de Tonti, the famous trusty lieutenant of La Salle, was reinstated in command of Fort St. Louis of the Illinois, with titles of captain and governor, by order of the French king Louis XIV. Tonti learned that La Salle was in trouble somewhere in New Spain (Texas), and organized an expedition for his relief. On Feb. 16th, 1686, he left Fort St. Louis, with 30 Frenchmen and 5 Indians, descended the Illinois and Miss, rivers to the Gulf, and scoured the coast for miles, but saw no sign of his great chief. He wrote a letter for La Salle, which he committed to the care of a chief of the Quinipissas for delivery, should opportunity offer, and retraced his way up the Miss. River to the mouth of the Arkansaw, which latter river he ascended to the village of the Arkensa Indians. There, on lands which La Salle had already granted him, he stationed six of his men, who volunteered to remain in hopes of hearing from the distant commander. This was the origin of the Poste aux Arkansas. La Salle was murdered by the traitor Duhaut, one of several ruffians among his own men who conspired to his foul assassination, some say on one of the tributaries of the Brazos, at a spot which has been supposed to be perhaps 40-50 m. N. of present town of Washington, Tex.; the date is Mar. 19th or 20th, 1687. Seven of the survivors of La Salle’s ill-starred colony at Fort St. Louis of Texas, reached Arkansas Post after a journey computed at the time to have been 250 leagues, in the summer of 1687, and found Couture and De Launay, two of the six whom Tonti had stationed there the year before. (See Wallace, Hist. 111. and La., etc., 1893.) This Tonti (or Tonty), b. about 1650, died at Mobile, 1704, was the son of Lorenzo Tonti, who devised the Tontine scheme or policy of life insurance. Arkansas Post was the scene of Laclede’s death, June 20th, 1778. The place was taken by the Unionists from the Confederates, Jan. nth, 1863.” Coues, Elliott. The expeditions of Zebulon Montgomery Pike, vol. 11, 560 n. 21.

The Act of Congress of March 2, 1819, creating the territory of Arkansaw, established the capital at the “post of the Arkansaw”, where it continued until 1821, when by the legislature it was removed to “the town at the Little Rock.”[

]

- This massacre is said to have taken place in what is now Saline County, Missouri.[

]

- Stoddard, Major Amos. Sketches, Historical and Descriptive of Louisiana, 39, 41, 45, 147.[

]

- Zebulon Montgomery Pike was born in Lamberton, New Jersey, January 5, 1779. Passing through various grades in the army he was commissioned Brigadier-general March 12, 1813. Early in that year he was appointed adjutant and Inspector-general of the army on the northern frontier. He was killed in an attack upon York, Upper Canada, April 27, 1813.[

]

- Coues, Elliott. The Expeditions of Zebulon Montgomery Pike, vol. ii, 415.[

]

- James B. Wilkinson, the son of General James Wilkinson, was born in Maryland; he was commissioned first-lieutenant in the army September 30, 1803, and captain October 8, 1808. He died September 7, 1813. Wilkinson’s account of his expedition is contained in Coues, Elliott, op. cit., vol. ii, 538-561.[

]

- Coues, Elliott, op. cit., vol. ii, 827.[

]

- Coues, Elliott, op. cit., vol. ii, 835.[

]

- American State Papers, “Indian Affairs” vol. i, 705.[

]

- Dunbar’s interesting journal of that expedition was deposited with the American Philosophical Society in 1817 and was published in Documents Relating to the Purchase and Exploration of Louisiana. New York, 1904.[

]

- Thwaites, R. G., editor, Early Western Travels, vol. xvii, 66ff; American Historical Association Annual Report for IQ04, 168 ff.[

]

- American State Papers, “Indian Affairs” vol. i, 729.[

]

- Pierre and Auguste Chouteau negotiated for the United States a large number of treaties with the Indian tribes in the early years after the Louisiana Purchase.[

]

- Manuel Lisa, a Spaniard, was born in Louisiana in 1776. He made several voyages from New Orleans up the Mississippi River in connection with the Indian trade and located in Saint Louis in 1799; and engaged at first in the Osage trade of which he obtained a monopoly from the Spanish government. Lisa made his first voyage up Missouri River in 1807, and from that time exercised a commanding influence in the fur trade out of Saint Louis. He died in that city August 12, 1820.[

]

- In 1802 the exclusive privilege of trading with the Osage was given by the Spanish authorities to Manuel Lisa, Charles Sanguinet, Francis M. Beniot, and Gregoire Sarpy. The next year at the instance of Sarpy the grant was revoked and given to him, without notice to the other grantees. After the Louisiana Purchase was consummated, Sarpy filed a claim against the government for damages on account of the loss of this monopoly. In 1814 the Committee of Claims of the House of Representatives reported against his claim. American State Papers, “Claims” vol. i, 432.[

]

- Near the site of the present town of Claremore, Oklahoma.[

]

- American State Papers, “Indian Affairs” vol. i, 708.[

]

- Hosmer, James R. History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, vol. i, 8.[

]

- Coues, Elliot, op. cit., vol. ii, 529, 557.[

]

- American State Papers, “Indian Affairs” vol. i, 765. Kappler, Charles J. compiler and editor. Indian Affairs, Laws and Treaties, vol. ii, 69.[

]

- “Major Lovely at the commencement of the War of the Revolution received a Commission in the Virginia line of the regular Army and continued in that line to the end of that war. At the capture of Burgoyne he belonged to a select Corps under Command of then Colonel Morgan. During his life he continued an undeviating friend to his adopted Country. About the commencement of the American revolution he came from Dublin where he had acquired the information & the manners of a gentleman. He lived some time in the family of Mr. Madison the father of the late President.” – Colonel Return J. Meigs to the Acting Secretary of War June 2, 1 817, Indian Office, Retired Classified Files, 1817 Cherokee Agency.[

]

- Lovely to General Clark, Governor of Missouri Territory, August 9, 1814, ibid., 1814, Cherokee Agency on Arkansas.[

]

- Lovely to Meigs, ibid., 1815, Cherokee Agency on the Arkansas.[

]

- Lovely to Clark, January 20, 1816, ibid., 1816, Cherokee Agency on the Arkansas.[

]

- Nuttall says: [Thwaites, op. cit., vol. xiii, 236] “The low hills contiguous to the falls of this river [Verdigris] and on which there exist several aboriginal mounds, were chosen by the Cherokees and Osages to hold their council, and to form a treaty of reciprocal amity as neighbors.”[

]

- U.S. House, Documents, 20th congress, first session, no. 263, Letter from Secretary of War concerning settlement of Lovely’s Purchase, 38.[

]

- Niles Register (Baltimore), vol. xiii, 74.[

]

- Niles Register (Baltimore), vol. xiii, 80.[

]

- Thwaites, op. cit., vol. xvii, 20.[

]

- Thwaites, op. cit., vol. xiii, 192.[

]