In the early 2000’s, the Ortona site was studied by archaeologists from several southern Florida universities under the direction of Archaeologist Bob Carr, Executive Director of the Archaeological and Historical Conservancy, Inc. 1 The Ortona Archaeological Zone received a flurry of publicity from articles in several major newspapers around the United States. It was designated a county park then promptly forgotten by most members of the archaeological profession. 2 The park is open to the public, but is poorly maintained and contains very little information that would enable the public to understand the site. The park’s sandy trails are most typically used by recreational hikers and bicyclists.

Ortona’s primary period of occupation was between 300 AD and 1150 AD, but (probably) Calusa People continued to occupy the site up until the 1600s. 3 The period of greatest growth was between 550 AD and 800 AD. This is exactly the period when Classic Period Maya city states to the south exploded with population. 4 This time of prosperity has been linked to ideal climatic conditions for agriculture in that region of the world.

The Calusahatchee River is a large river that flows about a hundred miles from Lake Okeechobee to the Gulf of Mexico near Fort Myers. Early wooden dugout canoes were used in Florida to travel the Everglades, plus the many lakes of the region and along rivers. A canoe would travel on a river to Lake Okeechobee. From the lake one could select another stream or canal to continue a journey. 5

Lake Okeechobee was a natural transportation hub. Trade from the east coast could cross the lake, go west on the Calusahatchee to the gulf, and return. To the north the Gulf coastline has more rivers that go inland hundreds of miles. Such travel would be an efficient way for ideas and cultural values to spread.

Around 900 AD southern Florida became dominated by a unified province composed of the Wakata-Mayami people around Lake Okeechobee, the Tekesta People on the southeastern Atlantic Coast and the ancestors of the Calusa on the southwestern Gulf Coast. 6 At this time the people of southern Florida all started producing the same style of pottery (Belle Glade III) while 500 miles to the north, a trading center was established on the Ocmulgee River in what is now Macon, GA. 7

After the period of rapid growth, Wakata (to the east) became the dominant town of the densely populated Lake Okeechobee Basin. 8 The site was still occupied until around 1150 AD, but its population was diminished. At virtually the same time, the acropolis of Ocmulgee was abandoned. 9

The intersection of trade routes becomes a large town and religious center

Beginning around 300 AD or earlier, a village formed near the shoals of the Calusahatchee. 10 This river was the principal route for bulk goods moving by canoe to and from the Gulf of Mexico and Lake Okeechobee. A series of limestone ledges in the river forced canoeists to beach their craft and then use porters to help carry the heavy dug-out canoes and cargo along the river to the end of the shoals. Overland trade paths intersected the portage trail.

These intersections of trade routes created a perfect location for people to trade and socialize. Generations of commercial and social intercourse made the area to the north of the shoals an ideal location for erecting religious shrines and burial mounds. Over time, more and more people lived in Ortona as the labor needs of transportation, commerce and religion increased. It is a typical pattern seen around the world. Many cities in Europe and the United States were originally trading villages adjacent to shoals.

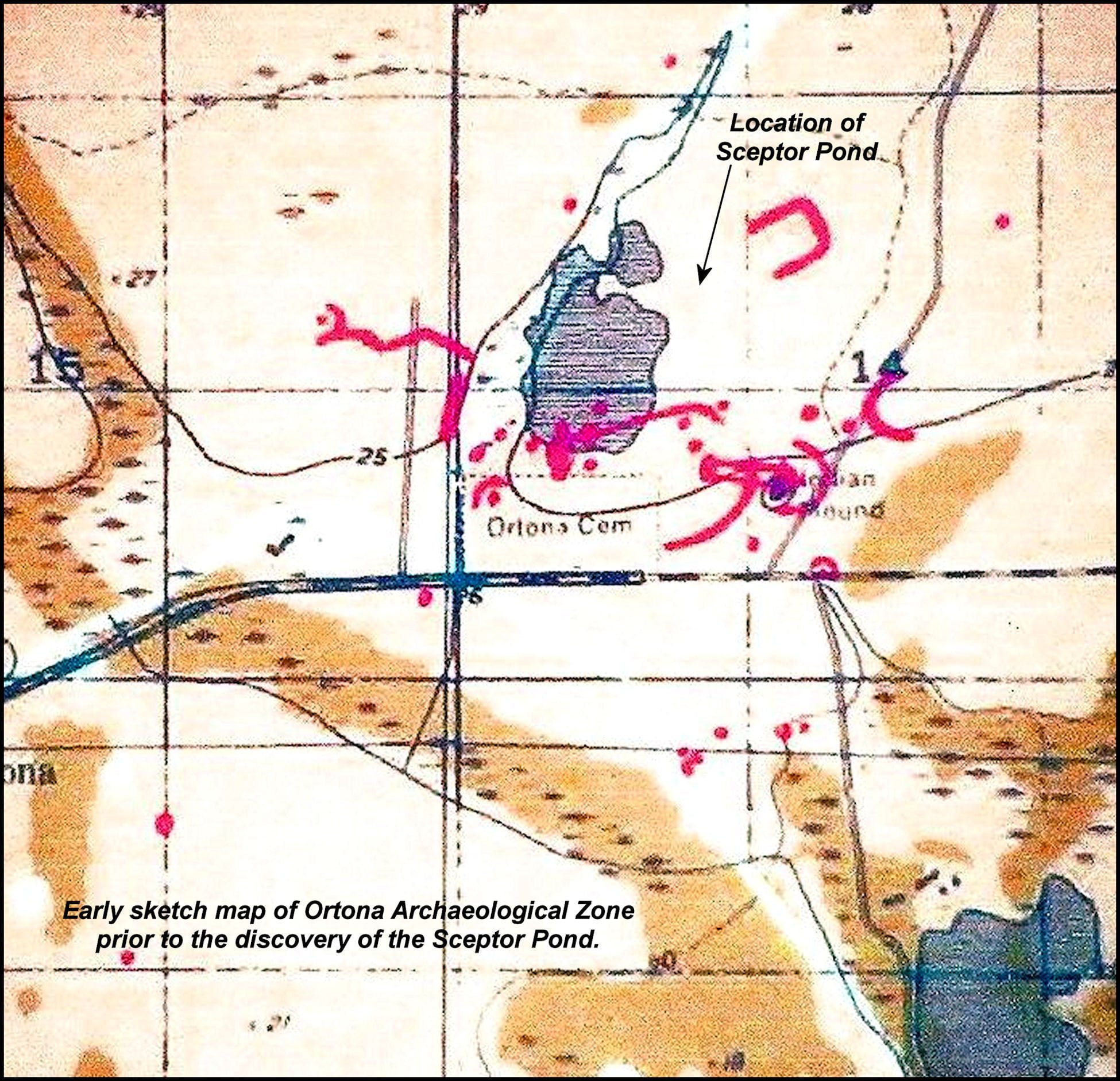

Architects can discern much about the social and political structures of ancient towns by their spatial organizations. This certainly is the case with Ortona. In the site plan of Ortona, associated with this series in Access Genealogy, the placement of the major buildings seems random. Individual structures were oriented to the solar azimuth, but very few were aligned with each other. Most public buildings are in clusters dispersed throughout the eastern side of the town.

A large circular plaza, defined by many houses and a large temple complex is in the southeastern corner, adjacent to the beginning of the rapids, where canoes once had to portage. The location eventually became the entrance to an extensive canal system, which bypassed the rapids and allowed bulk goods to be delivered throughout the town; More about that below. There is also no evidence today of any type of fortifications. In fact, the Ortona site is quite vulnerable from a military perspective.

The arrangement of the buildings suggests that during much, or all of the town’s development, political power was not focused into one person, or one family. The clusters of major structures suggest that there were several religious and economic groups sharing power together.

This same type of random land development patterns are seen a Chichen Itza, in the northern Yucatan Peninsula. 11 Chichen Itza was dominated by an oligarchy of wealthy merchant families and cults that focused on the worship of particular gods or goddesses. Its Great Sun (Mako Hene ~ CEO) was elected from the nobility and had limited powers. This is the same system of government found among the ancestors of the Creek and Apalache Indians, farther north in eastern Alabama, northern Georgia, western North Carolina, western South Carolina and eastern Tennessee.

The lack of fortifications, combined with the extensive development of a canal system around & within the town, strongly suggests that commerce was the most important concern of the community. There were obviously no security threats or the same engineering skills used for constructing canals would have been applied to fortresses, moats and palisades. As built, Ortona would have been extremely vulnerable to attack from the north or the east, since no canals or river would have hindered an enemy force.

There were several complexes scattered around the town, which appear to have important cultural or religious functions. [See site plan.] This dispersed pattern of structures with religious or cultural usages suggest that over time Ortona became a regional cultural center to which people made pilgrimages. The economic motivation behind the investments into such large regional facilities would have been identical to the construction of mega-stadiums for professional sports today.

The indigenous people of southern Florida did have some form of regional government. Continuous canals and raised causeways linked all the towns in an efficient transportation network. 12 Someone somewhere had to plan in advance, where their “interstate canals and highways” would go. Someone somewhere had to obtain and supervise the labor necessary to construct these large public works projects. In subsequent articles on Ortona, we will discuss the regional transportation system that made Ortona and its sister cities possible.

Citations:

- The Archaeological and Historical Conservancy Website[

]

- Ortona Indian Mounds Park[

]

- Carr, Robert S., Dicke, David & Mason, Marilyn. “Archaeological investigations at the Ortona Earthworks and Mound.” The Florida Anthropologist, Vol. 48, No. 4. December 1995.[

]

- Rose, Jon Janson. “A Study of Late Classic Maya Population Growth at La Milpa, Belize.” University of Pittsburg, 2000.[

]

- Carr, Robert S. Ancient Native American Canal System. Ortona, Florida GPR Survey April, 2004.[

]

- Johnson, William G. (1992.) “Part II: Archaeological Contexts: Chapter 11. Lake Okeechobee Basin/Kissimmee River, 3000 B.P. to Contact.” Florida’s Cultural Heritage: A View of the Past. Tallahassee, Florida: Division of Historical Resources, Florida Department of State: pp. 81-90.[

]

- Thornton, Richard. Ancient Roots III: The Indigenous Peoples and Architecture of the Ocmulgee-Altamaha River Basin. Raleigh: Lulu Publishing. 2008.[

]

- Carr, Robert S. Ancient Native American Canal System. Ortona, Florida GPR Survey April, 2004.[

]

- Carr, Robert S. Ancient Native American Canal System. Ortona, Florida GPR Survey April, 2004.[

]

- Carr, Robert S. Ancient Native American Canal System. Ortona, Florida GPR Survey April, 2004.[

]

- Beniamino Volta, Thomas E. Levy & Geoffrey E. Braswell. “The virtual Chichén Itzá project: modeling an ancient Maya city in Google SketchUp.” Antiquity, Volume 083 Issue 321, September 2009.[

]

- Carr, Robert S. Ancient Native American Canal System. Ortona, Florida GPR Survey April, 2004.[

]