Medawin, or to Meda: To exhibit the power of the operator, or officiating priest, in the curative art, an elongated lodge is expressly erected from poles and foliage newly cut, and particularly prepared for this purpose. This work is done by assistants of the society, who obey specific directions, but are careful to exclude such species of wood or shrubbery as may be deemed detrimental to the patient. The highest importance is attached to this particular, as well as to other minor points, in the shape, position, or interior arrangements of the lodge. For to discover any over sight of this kind after the ceremony is past, is a sufficient, and, generally, satisfactory cause of failure. When the lodge is prepared, the master of the ceremonies, who has been applied to by the relatives of a sick person, proceeds to it, taking his drum, rattles, and other instruments of his art. He is met by other members of the meda who have been invited to be present and participate in the rites. Having gone through some of the preliminary ceremonies, and chanted some of the songs, the patient is introduced. If too weak to walk, the individual is carried in on a bed or pallet, and laid down hi the designated position. The exactness and order which attend every movement, is one of its peculiarities. No one may enter who has not been invited, but spectators are permitted to look on from without. Having entered the arcanum, and all being seated, a mysterious silence is observed for some time. Importance is attached to the course of the winds, the state of the clouds, and other phenomena of the heavens; for it is to be observed that these ceremonies are conducted on open elevated places, and the lodge is built without a roof, so that the minutest changes can be observed. It is a fact worthy of notice, that attempts of the medas to heal the sick are only made when the patients have been given over, or failed to obtain relief from the muske-ke-win-in-ee, or physician. If success crown the effort, the bystanders are ready to attribute it to superhuman power; and if he fail, there is the less ground to marvel at it, and the friends are at least satisfied that they have done all in their power. And in this way private affection is soothed, and public opinion satisfied. Such are the feelings that operate in an Indian village.

Admissions to the society of the Meda are always made in public, with every ceremonial demonstration. To prepare a candidate for admission, his chief reliance for success is upon his early dreams and fasts. If these bode good, he is induced to persevere in his preparations, and to make known to the leading men of the institution, from time to time, the results. If these are approved, he is further prepared by resorting to the process of the steam bath. In this situation he is met by older professors, who are in the habit of here exchanging objects of supposed magical of medicinal virtue. The candidate is further initiated in such prime secrets as are deemed infallible in the arts of healing or hunting, or resisting the power of enchantment or witchcraft in others. The latter is known, in common parlance, in the Indian country, as the power of throwing, or resisting the power to throw, bad medicine.

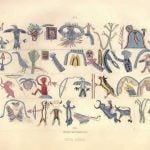

I had observed the exhibitions of the Medawin, and the exactness and studious ceremony with which its rites were performed, in 1820, in the region of Lake Superior, and determined to avail myself of the advantages of my official position, in 1822, when I returned as a Government Agent for the tribes, to make further inquiries into its principles and mode of proceeding. And for this purpose, I had its ceremonies repeated, in my office, under the secrecy of closed doors, with every means of both correct interpretation and of recording the result. Prior to this transaction, I had observed, in the hands of an Indian of the Odjibwa tribe, one of those symbolic tablets of pictorial notation, which have been sometimes called Music Boards, from the fact of their devices being sung off, by the initiated of the Meda Society. This constituted the object of the explanations, which, in accordance with the positive requisitions of the leader of the Society, and three other initiates, was thus ceremoniously made. The following plate, 51, is an exact facsimile of it, the original tablet having been run by Mr. Peter Maveric through his rolling press, in the city of New York, in 1825.

It is to these figures that the term Mnemonic symbols is applied. They are called Nugamoon-un by the natives, that is to say, songs. They are the second grade of symbolic pictures of the character of Ke-ke-no-win, or instructions. They are merely suggestive to the memory, of the words of the particular song or chant, of which each figure is the type. The words of these songs are fixed, and not variable, as well as the notes to which they are sung. But these words, to be repeated, must have been previously learned by, and known to, the singer. Otherwise, although their ideographic character and value would be apparent, and would not be mistaken, he would not be able to sing the words of the song. Sounds are no further preserved by these mnemonic signs, than is incident, more or less, to all pure figurative or representative pictures. The simple figure of a quadruped, a man or a bird, recalls the name of a quadruped, a man or a bird. It recalls to the Indian s mind the corresponding sounds, in his vocabulary of awaysee, ininee, penaysee. This is of some value, in the interpretation of the historical inscriptions, or that class of them, for which their vocabulary provides the term of Muz-zin-au-bik-oan, or rock-writings. It conveys the names of the actors, with their respective tribes, and the clans or leading families of the tribes. We may thus recall something of the living language from the oblivion of the past, by the pictorial method. Mnemonic symbols are thus at the threshold of the hieroglyphic. I suspect that each chant has a key symbol and that it is the character of this particular symbol, which operates to direct the memory, as to the number, locality, color of paper or type, or other particular circumstances, on the page of a printed book, are known, in some cases, to recall, or energize the memories of learners.

The Plate number 51, embraces two parts. 1. The songs of the Meda proper, which are regarded as most sacred. 2. Songs of the Wabeno. We will commence with the former, which consists of twenty-two key-symbols, denoting the same number of independent chants.

Songs of the Meda Proper

Figure 1. A medicine lodge filled with the presence of the Great Spirit, who, it is affirmed, came down with wings, to instruct the Indians in these ceremonies. The meda, or priest, sings

Mon e do

We gum ig

Ah to dum ing

Ne we peen de gay. 1

The Great Spirit’s lodge you have heard of it. I will enter it.

While this is sung, and repeated, the priest shakes his shi-shi-gwun, and each member of the society holds up one hand in a beseeching manner. All stand, without dancing. The drum is not struck during this introductory chant.

Figure 2. A candidate for admission crowned with feathers, and holding, suspended to his arm, an otter-skin pouch, with the wind represented as gushing out of one end. He sings, repeating after the priest, all dancing, with the accompaniment of the drum and rattle:

Ne sau moo zhug

We au ne nay

Ozh ke bug ge ze

We ge waum

Ne peen de gay.

I have always loved that that I seek. I go into the new green leaf lodge.

Figure 3 marks a pause, during which the victuals prepared for the feast are introduced.

Figure 4. A man holding a dish in his hand, and decorated with magic feathers on his wrists, indicating his character as master of the feast. All sing,

Ne mau tau

ne go

Ne kaun.

I shall give you a share, my friend.

Figure 5. A lodge apart from that in which the meda-men are assembled, having a vapor-bath within it. The elder men go into this lodge, and during the time of their taking the bath, or immediately preceding it, tell each other certain secrets relative to the arts they employ in the Medawin. The six heavy marks at the top of the lodge indicate the steam escaping from the bath. There are three orders of men in this society, called

- Meda.

- Saugemau.

- Ogemau.

And it is in these secret exchanges of arts, or rather the communication of unknown secrets from the higher to the lower orders, that they are exalted from one to another degree.

The priest sings, all following and beating time on their drums with small sticks, while they move round the lodge with a measured tread:

We ge waum

Peen de gay

Ke kaun

E naun

Sain goon ah wau.

I go into the bath I blow my brother strong.

Figure 6. The arm of the priest, or master of ceremonies, who conducts the candidate, represented in connection with the next figure.

Figure 7. The goods, or presents given, as a fee of admission, by the novitiate.

Ne we hau gwe no

Ne we hau gwe no

No sa, ne kaun.

I wish to wear this, my father my friend.

Figure 8. A meda-tree. The recurved projection from the trunk denotes the root that supplies the medicine.

Au ne i au ne nay

Au ne i au ne nay

Pa zhik wau kooz e

Ke mit tig o me naun

Ke we taush kow au.

What! my life, my single tree! we dance around you.

Figure 9. A stuffed crane-skin, employed as a medicine-bag. By shaking this in the dance, plovers and other small birds are made, by a sleight-of-hand trickery, to jump out of it. These, the novitiates are taught, spring from the bag by the strong power of necromancy imparted by the skill or supernatural power of the operator. This is one of the prime arts of the dance.

Nin gau

Wau bum au

A zhe aun

Kau zhe go wid

A zhe aun.

I wish to see them appear that that has grown I wish them to appear.

Figure 10. An arrow in the supposed circle of the sky. Represents a charmed arrow, which, by the power of the meda of the person owning it, is capable of penetrating the entire circle of the sky, and accomplishing the object for which it is shot out from the bow.

Au neen, a zhe me go

Me day we, in in e wau

I. e. e. me da, me gun ee.

What are you saying, you mee dá man? This this is the meda bone.

Figure 11. The Ka kaik, a species of small hawk, swift of wing, and capable of flying high into the sky. The skin of this bird is worn round the necks of warriors going into battle.

Ne kaik-wy on

Tau be taib way we turn.

My kite’s skin is fluttering.

Figure 12. The sky, or celestial hemisphere, with the symbol of the Great Spirit looking over it. A Manito s arm is raised up from the earth in a supplicating posture. Birds of good omen are believed to be in the sky.

Ke wee tau gee zhig

Noan dau wa

Mon e do.

All round the circle of the sky I hear the Spirit s voice.

Figure 13. The next figure denotes a pause in the ceremonies. Figure 14. A meda-tree. The idea represented is a tree animated by magic or spiritual power.

Wa be no

Mit tig o

Wa be no

Mit tig o

Ne ne mee

Kau go

Ne ne mee

Kau go.

The Wabeno tree it dances.

Figure 15. A stick used to beat the Ta-wa-e-gun or drum.

Pa bau neen

Wa wa seen

Neen bau gi e gun.

How rings aloud the drum-stick’s sound.

Figure 16. Half of the celestial hemisphere an Indian walking upon it. The idea symbolized is the sun pursuing his diurnal course till noon.

Nau baun

A gee zhig a

Pe moos au tun aun

Geezh ig.

I walk upon half of the sky.

Figure 17. The Great Spirit filling all space with his beams, and enlightening the world by the halo of his head. He is here depicted as the god of thunder and lightning.

Ke we tau

Gee zhig

Ka te kway

We tee”m aun.

I sound all round the sky, that they can hear me.

Figure 18. The Ta-wa-e-gun, or single-headed drum.

Ke gau tay

Be tow au

Neen in tay way e gun.

You shall hear the sound of my Ta-wa-e-gun.

Figure 19. The Ta-wa-e-gonse, or tambourine, ornamented with feathers, and a wing, indicative of its being prepared for a sacred use.

Kee nees o tau nay

In tay way e gun.

Do you understand my drum?

Figure 20. A raven. The skin and feathers of this bird are worn as Head ornaments.

Kau gau ge wau

In way aun

Way me gwun e aun.

I sing the raven that has brave feathers.

Figure 21. A crow, the wings and head of which are worn as a headdress.

In daun daig o

In daun daig o

Wy aun Ne ow way.

I am the crow I am the crow his skin is my body.

Figure 22. A medicine lodge. A leader or master of the Meda society, standing with his drum-stick raised, and holding in his hands the clouds and the celestial hemisphere.

Ne peen de gay

Ne peen de gay

Ke we ge waun

Ke we ge waun.

I wish to go into your lodge I go into your lodge.

The idea of the sacred word Meda, which appears to be made prominent by these chants, is a subtile and all-pervading Principle of Power (whether good, or merely great power is not established by any allusions) which is to be propitiated by, or acted on, through certain animals, or plants, or mere objects of art, and thus brought under the control of the Meda-man, or necromancer. He exhibits to the initiates and the members of his lodge fraternity, a series of boasting and symbolic declamation. This ceremony is called a medicine dance, and the lodge a medicine lodge. But the word mus-ke-ke, or medicine, does not occur in it, nor is there any allusion to the healing art, except in a single instance, in the chant No. 8, in which the term “Au koozze” occurs. This is the third person of the indicative, he (or she), sick. The operators are not mus-ke-ke-win-in-ee, or physicians, but Meda-win-in-ee, that is Meda-men. They assemble, not to teach the art of healing, but the art of supplicating spirits. They do not rely on physical, but supernatural power. It is, indeed, a perversion of terms to call the institution a medicine society. Its members are not professors of the mus-ke-ke-win, but the Medawin not medicine-men, but necromancers, or medical magii.

Citations:

- The initial letter of each line is printed in capitals to facilitate the reading.[↩]