During the 1500s and early 1600s, when Spanish explorers were first making contact with the indigenous inhabitants of the Florida, they made contact with a powerful nation on the southwest coast between Charlotte Harbor and Cape Sable. 1 The first contact was made in 1513 by Juan Ponce de Leon, when he landed at the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River in southwest Florida. His landing boats were attacked by Calusa war canoes, lined with round shields. Ponce de Leon’s description of the canoes was identical to murals of Chontal Maya war canoes in the Yucatan Peninsula.

The region where most of its towns lay was in present day Charlotte and Lee Counties. 2 Calusa village sites can be found along the western half of the Caloosahatchee River. Various Spanish accounts called them either Calus, Calius, Caalius or Carlos. Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, a Spaniard held captive by the Calusa in the 16th century, recorded that Calusa meant fierce people in their language. This may or may not be true. Kalos is the Muskogean root word for “star.” 3

At the time of contact with Europeans, the Calusas had a rigid, hierarchal society. 4 All power was held by the king, village chiefs, war chiefs and priests. Typically, all of the leaders were close relatives of the king. Leadership was based on descent from ancient founders of their society. Those not descended from the founding oligarchy were all commoners. This suggests that at some time in the distant past, outsiders from a more advanced culture had arrived in the region and set themselves up as the elite. The power of the elite seems to have been also linked to the Calusa religion, which involved sorcery and communication with the souls of the dead.

There are no obvious breaks in the human occupation of southwest Florida or in the style of tools and weapons used to hunt and fish. Anthropologists have interpreted this fact as evidence that the population of the Calusa were aboriginal. However, the elite of the Calusa may have arrived in the region from another region. The technology of the commoners would not have changed, but the political structure and belief system would have.

Calusa Physical appearance

The physical appearance of the Calusa was a little different than the ancestors of the Muskogean tribes in the Southeastern United States, who lived 400 miles to the north. The Calusa averaged about 4” taller than the Spanish and about 8” shorter than the Creeks. 5 The men wore their disheveled hair down to their waist. The Calusa men only wore a leather breechcloth, while the women wore skirts woven from Spanish Moss and palmettos leaves. The commoners wore very few personal adornments.

Calusa Language

Academicians have long debated the Calusa language. For the most part, it has been lost, but approximately 50 to 60 place names survive in the colonial archives. 6 It was definitely a language distinct from those tongues spoken in northeastern and northwestern Florida. A hint of the Calusa’s origin comes from the name of their sun god, Toya. 7 Toya was a South American deity, who was also worshiped by the Native peoples on the southern coast of South Carolina. 8

Fra. Juan Rogel, a Jesuit missionary to the Calusa in the late 1560s, stated that the King of the Calusa was called Carlos, but he wrote that the name of the “kingdom” was Escampaba, with an alternate spelling of Escampaha. “Ha” or “haw” is a typical Itza Maya suffix. 9 Ahau means “lord” and “haw” is one of the words for river.

In his book on the Calusa, William Marquardt quoted a statement from the 1570s that “the Bay of Carlos … in the Indian language is called Escampapa, for the cacique of this town, who afterward called himself Carlos in devotion to the Emperor” (Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor). 10 The Escambia River is located on the extreme western end of the Florida Panhandle. This is a long distance from the known territory of the Calusa.

As stated above, Fra. Juan Rangel said that their name for themselves was Eskampa or Eskampama. “Eskam” appears to be the Castilian way of saying the Chontal Maya word, Is K’uum, which is the Calabaza squash – indigenous to the Caribbean Islands and definitely grown by the Calusas. 11 It is a small, round squash that grows rapidly, and has a many, small, sweet fruits.

Ha is a Chontal Maya locative suffix that was also used by the Creeks on the coastal plain of South Carolina. It roughly translates as “place of or territory of.” Haw is the Chontal Maya suffix for flowing water. Thus, a possible translation of the Eskampaha would be “Water-place of the Calabaza Squash (People.)”

Calusa Religion

The sun deity appears to have been a universal creator. The Calusa also believed that three supernatural beings ruled the universe. 12 They believed that humans had three souls, and that souls migrated to animals after death. The most powerful deity, Toya, governed the physical world, the second most powerful guided government leaders, while the third ruling deity influence the outcome of battles. This deity chose the victor in advance.

The Calusa also believed that the three souls were the pupil of a person’s eye, his shadow, and his reflection. 13 The soul in the eye’s pupil stayed with the body after death, and the Calusa would consult with that soul at the graveside. The other two souls left the body after death and entered into an animal. If a Calusa killed such an animal, the soul would then migrate to a lesser animal. Repeated killing of animals, containing human souls would eventually reduce the third soul to non-existence.

Shipwreck survivor, Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda described human sacrifice as a common practice: when the child of a cacique died. Every household was required to bring one of their children to be sacrificed. When the cacique died, his servants were sacrificed to join him. Each year a Christian was required to be sacrificed to appease a Calusa idol. 14

Calusa Food

The Calusa People were not large scale farmers. The Calusa women maintained small, raised bed kitchen gardens like their counterparts around Lake Okeechobee, where they grew Caloosa (Calabaza squash) tobacco, papayas, chili peppers and perhaps cassava. 15 However, seafood, plus wild fruits and nuts probably represented the 70% to 90% of their diet. The wild foods include Live Oak acorns, yucca root, coco plums and palm berries. Although the Calusa did cultivate some tropical fruits, no maize pollen has ever been discovered at a Calusa habitation site. The absence of corn cultivation and consumption sounds remarkably like the Huastecs of northern Vera Cruz State and southern Tamaulipas State.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Calusa were always dependent on marine life for the bulk of their nutrition. 16 These foods included many varieties of fish, dolphins, sharks, manatees, alligators, turtles, shrimp and other shellfish. Various indigenous and cultivated fruits, such as papaya completed their diets. When explorer, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés visited the Calusa in 1566, the Spaniards were only served fish and oysters. Archaeologists studied the remains of table scraps at a former Calusa village on the southwest Florida coast. They estimated that 93% of the calories in those villagers’ diets came from seafood.

The Calusa were highly skilled mariners and fishermen. They regularly trade with tribes in Cuba. From around 1150 AD until 1550 AD, the Calusas dominated southern Florida and controlled the maritime trade routes to the south. They were still regularly trading with Cuba in the 1700s and may have traded with the Maya in earlier times. The Calusa were aware of an advanced civilization in the Yucatan Peninsula. Trade was carried out in giant dug out cypress canoes with the prows turned upward like Chontal Maya boats. The Calusa also built smaller outrigger canoes with sails for travel on coastal waters and Lake Okeechobee. [See the illustrations in this article.]

Calusa Tools

The soft limestone in South Florida was unsuitable for making tools and weapons. 17 Greenstone was imported from the mountains of northern Georgia to make wedges and axes. All other tools were made from wood, shells, bone, the teeth of fish and sharks and petrified shark’s teeth. Fish nets were woven from local vegetative fibers. The Calusa did have some gold and silver ornaments, but there is no evidence that they learned how to make copper and brass weapons like the indigenous peoples of the Southern Highlands.

Community Planning and architectural traditions

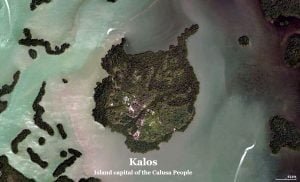

Around 0 AD a village was founded on an island near what is now Charlotte Harbor on the southwestern tip of Florida. 18 It was just one of many small fishing villages that composed what archaeologists label the Caloosahatchee Culture. The village slowly grew in population and evolved culturally to the point that it was the capital and major population center for a province that covered much of southwestern Florida. By the 1500s when the Spanish arrived in Florida, the Calusa People occupied coastal towns and villages from Tampa Bay to the Keys, and also had villages about half the distance inland to Lake Okeechobee and the Everglades.

Canals built by the Calusas survive to this day on the islands that they inhabited. Archaeologists have also found vestiges of a canal system between Lake Okeechobee and Charlotte Harbor. Canals seemed to have functioned as the principal “streets” of coastal Caloosa towns. They enabled the occupants to haul sea food and bulk commodities to landings very close to habitation areas. As can be seen in the upper illustration, Calusa Key was served by a network of canals, which divided up the island into neighborhoods. The largest canal might have been sixty feet wide at one time. The Calusa also excavated protected harbors inside islands at locations where major canals intersected.

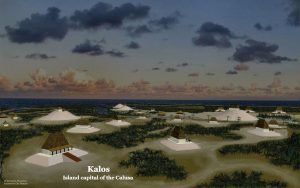

While supplying a cornucopia of seafood for the population, the islands and coastal marshlands of the Calusa province were also very vulnerable to hurricanes, high tides and tropical storms – which are almost annual occurrences. The flat surface of Calusa Key is barely above sea level. Tidal surges from larger hurricanes could have easily covered the island with water. In response to this serious environmental threat, their architecture and communities had unique features.

The temples and houses of the elite were on mounds and platforms created by immense piles of shells. The shell mounds would disperse the force of waves, wind and tidal surges, while raising the floors of buildings above flood levels. The commoners lived in houses constructed on timber piles, either individual structures or in platform villages.

It is likely that the Creek Indians who migrated into Florida in the 1700s and early 1800s (later becoming known as Seminoles) observed the elevated houses of the surviving Calusas and adapted the concept to their architectural traditions.

When the Spanish first visited the Calusa in the late 1500s, they observed that the people at that time lived in large communal buildings. As many as 600 people would live in one structure, set upon a mound of shells. The archaeological evidence of smaller buildings for individual families comes from an earlier period of time.

It is not known exactly when the Calusas shifted from single family homes to group living. However, the Spanish colonists of coastal Georgia and South Carolina in the 1560s also observed that some indigenous peoples there also lived in massive structures that could hold an entire village.

Calusa’s Rise to regional power

Around the year 900 AD, the Calusa Province merged with the Mayaimi province around Lake Okeechobee and the Tekesta villages on the southeast Florida coast in the vicinity of modern day Miami and Fort Lauderdale. At this time central political power shifted to Wakate (Guacata in Spanish). [See articles on Wakate and Ortona. Wakate was on the main canal crossing the Florida Peninsula. The root word, waka, means roadway, in several Mexican languages, while te means “people or ethnic group” in one of the Hitchiti-Creek Indian dialects. (See article on Wakata.) By this time, the style of pottery produced by the Calusa had changed to the Belle Glade III style of pottery produced around Lake Okeechobee. This pottery was tempered with the spines of freshwater sponges that thrived in the waters of southern Florida.

The powerful state in southern Florida dominated trade in much of the peninsula until around 1150 AD. At that time, the towns around Lake Okeechobee and the Saint Johns River lake country were abandoned and power apparently shifted to the Calusa; for their towns continued to thrive. The earliest known Arawak (Timucua) village sites date to this time period in northeastern Florida. At about the same time, the Toltec capital of Tula was sacked, and Ocmulgee (probably really named Waka) in central Georgia was abandoned. This was also the period when the large apartment buildings in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico were abandoned.

There was an extended, severe drought in northern Mexico and the Southwestern United States in the period around 1120-40 AD. 19 A less severe drought may have also occurred in what is now the Southeastern United States, also. Famine may have also disrupted trade or caused some ethnic groups to be aggressive. Another possibility is that abnormal weather elsewhere could have triggers massive hurricanes that destroyed entire provinces in the Florida Peninsula. More archaeological work is needed in Southern Florida before this period in Southeastern North America is fully understood.

Relatives of the Calusa on the South Atlantic Coast

The memoir of Captain René de Laudonnière, Commander of Fort Caroline, provides extensive information on the indigenous inhabitants of the coastal areas of Port Royal Sound, South Carolina, Georgia and northeastern Florida. The first chapter of the book describes the 1562 voyage of Jean Ribault that attempted to establish a colony at Port Royal Sound in South Caroline. 20 Apparently, most scholars in the past 435 years have not noticed that the cultures, religions and political titles of the tribes on Port Royal Sound were almost identical to those of the Calusa in southwest Florida. Both regions called their high king, Paracus, a South American ethnic name. Both regions worshiped the South American sun god, Toya. Both regions built massive structures to house hundreds of villagers. Since very little is known about the languages in the two regions, these cannot be compared. However, it is clear that there was a cultural connection between the southern tip of South Carolina and southwestern Florida.

Citations:

- MacMahon, Darcie A. and William H. Marquardt. (2004). The Calusa and Their Legacy: South Florida People and Their Environments. University Press of Florida; pp. 1-2.[

]

- Calusa. Wikipedia Encyclopedia.[

]

- Martin, Jack B. & Mauldin, Margaret McKane. (2000) A Dictionary of Creek/Muskogee. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; p. 64.[

]

- Granberry, Julian (2011). The Calusa: Linguistic and Cultural Relationships. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. pp. 19-24.[

]

- Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513-1763. University Press of Florida; pp. 33-35.[

]

- Granberry, Julian (2011). The Calusa: Linguistic and Cultural Relationships. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. pp. 19-24.[

]

- Carozza, Adam J. (2009) “New Port Ritchy, Myth and History of a City Built on Enchantment.” University of South Florida.[

]

- De Laudonnière, René (1586) L’histoire notable de la Floride, contenant les trois voyages faits en icelles par des capitaines et pilotes français. Translation by Charles C. Bennett (2001) Three Voyages. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press; p. 29.[

]

- Boot, Erik (2004) Itza Maya Dictionary. FAMSI website.[

]

- Marquardt, William H. (2004). “Calusa”. In R. D. Fogelson (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast (Vol. 14, p. 206). Smithsonian Institution.[

]

- Boot, Erik (2004) Itza Maya Dictionary. FAMSI website.[

]

- Winn, Ed (2003). Florida’s great king: King Carlos of the Calusa Indians. London: Buster’s Books; pp. 16-17.[

]

- Winn, Ed (2003). Florida’s great king: King Carlos of the Calusa Indians. London: Buster’s Books; pp. 16-17.[

]

- Worth, John (January 1995). “Fontaneda Revisited: Five Descriptions of Sixteenth-Century Florida“, The Florida Historical Quarterly, 73 (3), p. 339-352.[

]

- Widmer, Randolph J. (1998). The Evolution of the Calusa: A Nonagricultural Chiefdom on the Southwest Florida Coast. University of Alabama Press; pp. 234-241.[

]

- Widmer, Randolph J. (1998). The Evolution of the Calusa: A Nonagricultural Chiefdom on the Southwest Florida Coast. University of Alabama Press; pp. 234-241.[

]

- MacMahon, Darcie A. and William H. Marquardt. (2004). The Calusa and Their Legacy: South Florida People and Their Environments. University Press of Florida; pp. 29-70.[

]

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1998). Florida’s Indians from Ancient Time to the Present. University Press of Florida.[

]

- Foster, William C. (2012) Climate and Culture Change. Austin: University of Texas Press; pp. 49-64.[

]

- Bennett, Charles E. (2001) Three Voyages. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press; pp. 17-52. This book was presented as a translation of the original French text by René de Laudonnière, but since it presents verbatim translation errors made by Richard Hakluyt in 1587, it actually appears to be a modernization of the English in Hakluyt’s book. However, it surprisingly left out Hakluyt’s account of a voyage to avenge the massacre of Fort Caroline, perhaps because this account negates Jacksonville as the location of Fort Caroline.[

]