In 1976, while writing his dissertation for a Ph.D. in Anthropology, Archaeologist Bennie Keel was under heavy pressure to state that the Cherokees had lived in western North Carolina for at least 1000 years. 1 That was a new policy adopted by the State of North Carolina. What Keel did say was that only three probable Cherokee structures in North Carolina had produced radiocarbon dates before the 1720. Keel noted that there was a century long gap between the archaeological record of large towns with multi-roomed rectangular houses, large plazas and pyramidal platform mounds, and the small villages typical of the Cherokees with crude round huts and no mound building activities. What he did not dare say was that the earlier towns were virtually typical of the towns of the Creek Indians’ ancestors and that all towns visited by De Soto in North Carolina had Creek names.

The search for the history of the Cherokee Indians is very vague before 1721 and hits a brick wall around 1715. All the names of the original Lower Cherokee towns in South Carolina are Creek words, even though Cherokee history web sites say that they are ancient Cherokee words whose meanings have been lost. 2 All the recorded names of their chiefs during this early period are either English or Creek words. Wahachee, the leader of the Lower Cherokees in the Anglo-Cherokee War of 1759-1761 had a Creek name. It means that his ancestors came from the coast of Georgia! His real name, in Lower Cherokee and Itsate Creek, was Wahasi (pronounced Wă : hă : shē).

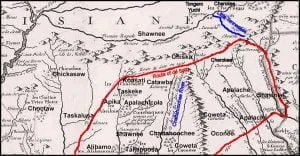

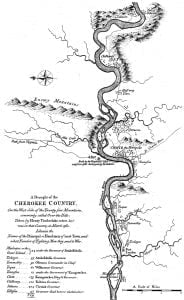

A similar situation exists at the Overhill Cherokee towns in the Tennessee River Basin. In 1540 when visited by Hernando de Soto there was a dense concentration of towns in the region with Maya and Muskogean names. Archaeologists think that mound-building stopped around 1600 AD. Some Muskogean towns were abandoned. Most continued with smaller populations. Some of the town names found in the de Soto Chronicles continued to appear on maps even after the Yamasee War in De Lisle’s 1718 map of the province of Louisiana. On the 1725 Herbert map of the Cherokee Nation, however, the towns mentioned by the De Soto Chronicles along the Little Tennessee River are not listed, but there are two new ones with Muskogean names, Tanasi and Tamatli.

The big surprise comes on the 1763 Timberlake map of the Cherokee Nation. Several of the town names mentioned by the De Soto Chronicles reappeared. Of the eight Overhill towns on the Little Tennessee River, six were Muskogean words and two were Arawak words. 3 All but one of the town chiefs had either the Maya-Itstate Creek title of Mako or the Muskogee title of Mikko. In fact, the real name of the most important Overhill town, Chote, was Itsate! That is an Itza Maya word which means Itza People. Chote comes from “Cho’I People.” Cho’I was one of the dialects spoken by the Itza Maya

In contrast, there is a continuous archaeological record in Georgia of the ancestors of the Creek Indians reaching back to at least 200 BC. Before that, the Creeks have a cultural memory, verified by DNA and linguistic analysis, of multiple origins in several parts of Mexico. Linguistics suggest that the first Muskogeans left northeastern Mexico around 400 BC and that waves of peoples continued to migrate from northern Mexico and Mesoamerica to Georgia up until around 1400 AD.

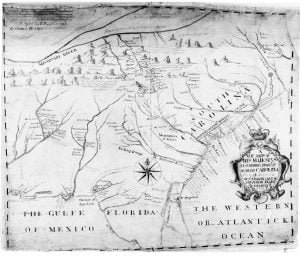

European maps also describe a major ethnic change in western North Carolina. Until the end of the Yamasee War in 1717, western North Carolina was shown on these maps to be occupied by the Talasee, Tuskegee, Shawnee and Apalache. The words Creek, Cherokee or Charakee didn’t appear on maps although the four ethnic groups, mentioned, did come together to form the Creek Confederacy.

Immediately after the Yamasee War, western North Carolina was left blank in the Delisle map, while the Cherokees were shown to live in extreme northeastern Tennessee along the Holston River and extreme northwestern South Carolina along the tributaries of the Savannah River. The same maps showed branches of the Creeks occupying villages along the Little Tennessee River and southward.

The 1725 Herbert map showed the Cherokees living around the confluence of the Tennessee and Little Tennessee River and in a narrow corridor along the Little Tennessee and Tuckasegee Rivers in North Carolina, plus the same locations in extreme northwestern South Carolina. In the 1725 map, no Cherokee villages were shown on the Holston River. The most northerly town was at the confluence of the Holston and French Broad Rivers.

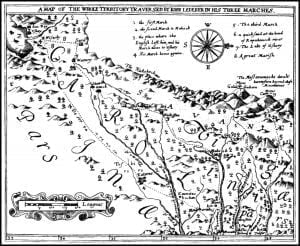

These 1717 and 1725 maps conflict with the colonial archives of Virginia and some late 17th century maps. Late 17th century explorers described Spanish and African towns and villages in northeastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia. On the other hand, the official 1676 map of the Colony of Carolina showed this exact same area occupied by the Rickohocken Indians. Some post-1725 maps often show the former territory of the Rickohockens in southwestern Virginia and northeastern Tennessee occupied by the Cherokees, even while other maps produced after 1754 labeled the same region, heavily settled by English subjects.

The replacement on British maps of the label “Rickohockens” with the words “Cherokees” has led many researchers to conclude that “Cherokee” was merely a new label for the “Rickohockens,” but was it? At least part of the Rickohockens relocated to near present-day Augusta, GA on the Savannah River in the late 1660s or early 1670s. They were arch-enemies of the Chorakee villages around the headwaters of the Savannah River. Perhaps, the Chorakees and Rickohockens were not the same ethnic group.

Just before he died in 1827, Cherokee Principal Chief Charles Renatus Hicks wrote eight letters to John Ross that explained the history of the Cherokee People. 4 He said that the Cherokees entered their current territory from the west at about the same time that white men were settling South Carolina. He said that their first principal town in the new land was Big Tellico on the Tellico River. Tellico was the Cherokee name for the Little Tennessee River. The original word was actually Tali-koa, which is Arawak for Tali-People. Tali was a town on the Little Tennessee River, visited by Hernando de Soto in June of 1540.

The Creek name of the river, prior to the Cherokee’s arrival was the Talasee River, actually written Tvlasi. Tvlasi mean “Offspring of Tula” – Tula being the original name of Teotihuacan in Mexico, the Itza Maya word for a large town and the Itaste Creek word for a large town.

Hicks stated that the mound builders in western North Carolina were weak because of population losses. The Cherokees killed or drove away the mound builders then burned their temples that were on top of the mounds. The Cherokees then built round council houses on top of the old mounds. He said that the Cherokees did not build any mounds themselves.

It should be explained that Charles Hicks was ¾ Scottish and that his Native grandmother was a Tamatli Creek from the Andrews Valley, east of present day Murphy, NC. Nevertheless, he was one of the most learned Cherokees of his day. His statements should be considered to be an accurate description of what the Cherokees believed their origin was in the 1820s. On the other hand, John Ross had virtually no Native American features. He was officially 1/8 Cherokee, but looked more like an Armenian or Sephardic Jew than anything else. His mother may have had much less Native American DNA than 1/4th.

The current version of Cherokee history as presented by the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in North Carolina is that the Cherokees have lived in the North Carolina Mountains for at least 10,000 years and that they were the ancestors of the Mays and Aztecs. 5 According to the museum, the Cherokees were the first people to cultivate corn, beans and squash. They built great temple mounds that faced large plazas, where the people held ceremonies. Their first capital was Kituwa, where they were ruled by hereditary priests named kitani. The people eventually became tired of the Kitani’s arrogance and killed them all. What the museum does not tell the public is that the ani-kitani priesthood was replaced by conjurers who acted as intermediaries with “spirits” who dwelled in sacred fires and springs.

It is interesting that kitani is an Alabama Indian word meaning, “sorcerer” – from the Alabama root verb meaning to start a fire. Kituwa is the Alabama word for “sacred fire.” Apparently, in the old days, the Alabama priests who maintained the sacred fires, knew a way to start fires that seemed like magic.

If the Native American core of the Cherokees originally entered from the west, and was not the same as the Rickohockens, it would explain how Europeans could be living in northeastern Tennessee, before the Cherokees appeared on the Little Tennessee River. The Rickohockens may have joined this core.

As stated earlier, the Lower Cherokees were not ethnically Cherokees, but splinter towns that broke ties with Creek mother towns in Georgia and elsewhere in South Carolina then became allies of villages across the mountains. They were the remnants left over from the ethnic cleansing of South Carolina in the late 1500s and 1600s. At most, their population numbered around 1200 persons at the beginning of the 18th century. 6 Until the first decade of the 18th century, they had been vassals of a ancient, powerful Muskogean town on an island in the Tugaloo River that was the capital of the Ustanoli people, just upstream from the official beginning of the Savannah River. As described in an earlier section, the Ustanali were visited by trade representatives of the French settlement at Fort Caroline in 1564 and 1565.

Perhaps in order to compete with their counterparts in North Carolina, late 20th century economic boosters in South Carolina mythicized the relatively small cluster of allied villages in the extreme corner of northwestern South Carolina into the “Great Cherokee Nation of South Carolina” that once encompassed most of the state. An official state website announces that the Cherokees were an Iroquoian people that arrived in the state at least 4000 years ago. 7They had to one-up North Carolina which originally claimed that the Cherokees had been there 1000 years; now it is 10,000 years. As result, people from throughout South Carolina, whose families think that they had an Indian ancestor proudly call themselves Cherokees.

Only at the anthropological museums of Tennessee do visitors find a reasonably accurate portrayal of known Cherokee history. The museums state that the Cherokees arrived in the eastern edge of the future state of Tennessee in the early 1700s and were pretty much gone after 1800. 8

Much of what is now presented about the Cherokee people prior to 1717 is basically, “History by proclamation.” Members of other Southeastern Native American tribes label it “Imperial History.” The truth is that no one knows where the non-Muskogean core of Cherokees was before the early 1700s. No archives, dictionaries or European archives justify the increasingly outlandish descriptions of the Cherokee’s mysterious past. There are several anthropologists and historians with PhD’s equally as guilty of this academic crime as the legion of people with 1/128th (or less) Native American ancestry, who have created “Official Cherokee History Websites.” The apparent goal of these efforts is the transform an early 18th century alliance of peoples in the Southern Appalachians into a master race that created all the civilizations in the Americas. The truth is something else, but still is an unsolved historical mystery.

Citations:

- Keel, Benny, Cherokee Archaeology: A Study of the Appalachian Summit, Knoxville: UT Press, 2001.[

]

- Chauga = Black Locust; Tokahle = Spotted People; Tamasee = Offspring of Tama (a major division of the Creek People); Okoni = born in water (a major division of the Creek People); Keowee = Division of Creeks based near present day Watkinsville, GA; Edistoa = Hybrid Arawak-Muskogean people originally on the South Carolina Coast, Katapa = Place of the Crown; Toksawe (Toxaway) = kitchen shed and Seneca = Spread Out.[

]

- Tamatli (Creek) = Tama People; Mialako (Creek) = Muskrat Island; Tanasi (Creek) = Offspring of Tanasa; Taskegi (Creek) – Woodpecker People; Itsate/Chote (Maya) = Itsa Maya People/Cho’i Maya People; Chillihowee (Creek) = Foreign speakers; Talasee (Creek) = Offspring of Tali; Seticoa (Arawak) = ? People; Toccoa (hybrid Muskogean-Arawak) = Spotted People; and Taliko (Creek -Tellico in English) = Bean.[

]

- Moulton, Gary E. (editor), The Papers of Chief John Ross, Norman, OK: University Of Oklahoma Press, 1985.[

]

- Duncan, Barbara, Cherokee Heritage Trails, Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2003; Last paragraph![

]

- Swanton, John W., The Indian Tribes of North America, Washington City: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1952; pp. 215-224.[

]

- Cherokee People[

]

- The Cherokee Indians: Tennessee’s First Citizens.[

]