As a marksman the Choctaw could not be surpassed in the use of the rifle. It mattered not whether his game was standing or running; a bullet shot from his rifle, when directed by his experienced eye, was a sure messenger of death. A shotgun was regarded with great contempt, and never used. The rifle, and the rifle alone, would he use. To surprise a Choctaw warrior or hunter in the woods see him before he saw you was a feat not easily accomplished; in fact, impossible by an experienced white woodsman, and extremely difficult even by the most experienced. His watchful and practiced eye was always on the alert, whether running, walking, standing or sitting; and his acute ear, attentive to every passing sound, heard the most feeble noise, which, to the white man’s ear was utter silence.

Years ago I had a Choctaw (full-blood) friend as noble and true as ever man possessed, and whom once to know was to remember with an esteem approaching the deepest affection; and of whom I was justly proud and in whom I took delight; and today, had I a hundred tongues, I could not express my appreciation of that noble friend. He was indeed a cordial to my heart oft imparting to me an earnest of happiness, which I thought had fled. Oft in our frequent hunts together, while silently gliding through the dense forests ten or fifteen rods apart, he would attract my attention by his well-known ha ha (give caution) in a low but distinct tone of voice, and point to a certain part of the woods where he had discovered an animal of some kind; and though I looked as closely as possible I could see nothing whatever that resembled a living object of any kind. Being at too great a mistake to risk a sure shot, he would signal me to remain quiet, as he endeavored to get closer. To me that was the most exciting and interesting part of the scene; for then began those strategic movements in which the most skillful white hunter that I have ever seen, was a mere bungler. With Deepest interest, not unmixed with excitement, closely watched his every movement as he slowly and stealthily advanced, with eyes fixed upon his object; now crawling noiselessly upon his hands and knees, then as motionless as a stump; now stretched full length upon the ground, then standing erect and motionless; then dropping suddenly to the ground, and crawling off at an acute angle to the right or left to get behind a certain tree or log, here and there stopping and slowly raising his head just enough to look over the top of the grass; then again be hidden until he reached the desired tree; with intense mingled curiosity and excitement, when hidden from my view in the grass, did I seek to follow him in his course with my eyes. Oft I would see a little dark spot not larger than 1113 fist just above the top of the grass, which slowly grew larger and larger until I discovered it was his motionless head; and had I not known he was there somewhere I would not have suspected it was a human head or the head of anything else; and as I kept my eyes upon it, I noticed it slowly getting smaller until it gradually disappeared; and when he reached the tree, he then observed the same caution slowly rising until he stood erect and close to the body of the tree, then slowly and cautiously peeping around it first on the right, then on the left; and when, at this juncture, I have turned joy eyes from him, but momentarily as I thought, to the point where I thought the game must be, being also eager to satisfy my excited curiosity as to the kind of animal he was endeavoring to shoot, yet, when I looked to the spot where I had just seen him lo! He was not there; and while wondering to what point of the compass he had so suddenly disappeared unobserved, and vainly looking to find his mysterious whereabouts, I would be startled by the sharp crack of his rifle in a different direction from that in which I was looking for him, and in turning my eye would see him slowly rising out of the grass at a point a hundred yards distant from where I had last seen him. “Well, old fellow,” I then ejaculated to myself, “I would not hunt for you in a wild forest for the purpose of obtaining your scalp, knowing, at the same time, that you were somewhere about seeking also to secure mine; I would just call to you to come and take it at once and save anxiety.”

Talk about a white man out maneuvering an Indian in a forest, is an absurdity veritable nonsense.

Frequently have I proposed to exchange guns with George (that was his name simply George and nothing else) my double barrel shotgun for his rifle, but he invariable refused; and when I asked for his objection to my gun, he ever had but one and the same reply “Him push.” He did not fancy the reaction or “kicking” so oft experienced in shooting the” shotgun which George had, no doubt, once experienced to his entire satisfaction. Generous and faithful George! I wonder where you are today? If on the face of God’s green earth, I am sure humble though you may be there is one true heart above the sod that still beats in love for me.

It was truly wonderful with what ease and certainty the Choctaw hunter and warrior made his way through the dense forests of his country to any point he wished to go, near or distant. But give him the direction, was all he desired; with an unerring certainty, though never having been in that part of tire country before, he would go over hill and valley, through thickets and canebrakes to the desired point, that seemed incredible. I have known the little Choctaw boys, in their juvenile excursions with their bows and arrows and blow guns to wander miles away from their homes, this way and that through the woods, and return home at night, with out a thought or fear of getting lost; nor did their parents have any uneasiness in regard to their wanderings. It is a universal characteristic of the Indian, when traveling in an unknown country, to let nothing pass unnoticed. His watchful eye marks every distinguishing feature of the surroundings a peculiarly leaning or fallen tree, stump or bush, rock or hill, creek or branch, he will recognize years afterwards, and use them as land marks, in going again through the same country, Thus the Indian hunter was enabled to go into a distant forest, where he never before had been, pitch his camp, leave it and hunt all day wandering this way and that over hills and through jungles for miles away, and return to his camp at the close of the day with that apparent ease and unerring certainty, that baffled all the ingenuity of the white man and appeared to him as bordering on the miraculous. Ask any Indian for directions to a place, near or distant, and he merely points in the direction you should go, regarding that as sufficient information for any one of common sense.

In traveling through the Choctaw Nation in 1884, at one time I desired to go to a point forty miles distant, to which led a very dim path, at times scarcely deserving the name, and upon making inquiry of different Choctaws whom I frequently met along my way, they only pointed in the direction I must travel and passed on; and being ashamed to let it appear that I did not have sense enough to go to the desired point after being told the direction, I rode on without further inquiry, and by taking the path, at every fork that seemed to lead the nearest in the direction I had been told to travel, I, in good time, reached my place of destination. So, after all, the Choctaws told me all that was necessary in the matter.

The ancient Choctaw warrior and hunter left the domestic affairs of his humble home wholly to the management of his wife and children. The hospitalities of his cabin, however, were always open to friend or stranger, but before whom he ever assumed a calm and respectful reserve, though nothing escaped his notice. If questioned he would readily enter into a conversation concerning his exploits as a warrior and hunter, but was indifferent upon the touching episodes of home, with its scenes of domestic bliss or woe, though their tendrils were as deeply and strangely interwoven with the fibers of his heart as with those of any other of The human race. The vicissitudes of life, its joys and sorrows, its hopes and fears, were regarded as unworthy the consideration of a warrior and hunter; but the dangers, the fatigues and hardships of war and the chase as subjects only worthy to be mentioned. Yet, with all this, in unfeigned affection for his wife, children, kindred and friends; in deep anxiety for them in sickness and distress; in untiring efforts to relieve their necessities and wants; in anxiety for their safety in hours of danger; in fearless exposure of himself to protect them from harm ; in his silent yet deep sorrow at their death; in his un-assumed joy in their happiness; in these all Indians stand equal to any race of people that ever lived. And when roaming with him years ago in the solitudes of his native forests, and have looked upon him, whose nature and peculiar habits have been declared by the world to have no place with the rest of the human family, and then have gone with him to his humble, but no less hospitable, forest home, and there witnessed the same evidences of joy and sorrow, of hope and fear, of pleasure and pain that are every where peculiar to man s nature, I could but be more firmly established in that which I long had known, that the North American Indian, from first to last, had been wrong fully and shamefully misrepresented, and though in him are blended vindictive and revengeful passions, so much condemned by the civilized world, yet I found these were equally balanced by warm, generous, and noble feelings, as were found in any class of the human race:

To the ancient Choctaw warrior and hunter, excitement of some kind was indispensable to relieve the tedium of the nothing-to-do in which a great part of his life was spent. Hence the intervals between war and hunting were filled up by various amusements, ball plays, dances, foot and horse races, trials of strength and activity in wrestling and jumping, all of which being regulated by rules and regulations of a complicated etiquette.

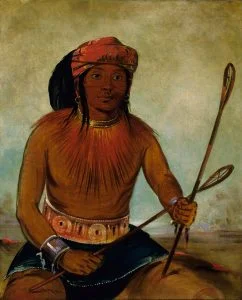

But the Tolik (Ball play) was the ultimatum of all games the sine qua non of all amusements to the Indians of the south; and to which he attached the greatest importance, and in the engagement of which his delight reached its highest perfection, and in the excelling of which his ambition fell not below that of him who contested in the Olympic games of ancient Greece.

A Choctaw Tolik seventy years ago, was indeed a game that well might have astonished the Titan, and diverted them, protem, at least, from their own pastime. But when I look back through the retrospective years of the long past to that animating scene, and then read in recent years the different attempts made by many through the journals of the day to describe a genuine Choctaw Ball-play of those years ago, it excites a smile and only intensifies the hold memory retains of that indescribable game. No one, who has not witnessed it, can form a just idea of the scene from any description given; for it baffles all the powers of language and must be seen to be in any way comprehended. The base ball play of the present day, so popular among the whites, in point of deep interest and wild excitement produced in the spectator, when compared to the Chashpo Tolik (Ancient Ball-play) of the Choctaws east of the Mississippi river, bears about the same relation that the light of the crescent moon does to the midday light of the mighty orb of day in a cloudless sky. However”, I will attempt a description, though well aware that after all that can be said, the reader will only be able to form a very imperfect idea of the weird scene.

When the warriors of a village, wearied by the monotony of every day life, desired a change that was truly from one extreme to that of another, they sent a challenge to those of another village of their own tribe, and, not infrequently, to those of a neighboring tribe, to engage in a grand ball play. If the challenge was accepted, and it was rarely ever declined a suitable place was selected and prepared by the challengers, and a day agreed upon. The Hetoka (ball ground) was selected in some beautiful level plain easily found in their then beautiful and romantic country. Upon the ground, from three hundred to four hundred yards apart, two straight pieces of timber were firmly planted close together in the ground, each about fifteen feet in height, and from four to six inches in width, presenting a front of a foot or more. These were called Aiulbi. (Ball posts.) During the intervening time between the day of the challenge and that of the play, great preparations were made on both sides by those who intended to engage therein. With much care and unaffected solemnity they went through with their preparatory ceremonies

The night preceding the day of the play was spent in painting, with the same care as when preparing for the warpath, dancing with frequent rubbing of both the upper and lower limbs, and taking their “sacred medicine.”

In the mean time, tidings of the approaching play spread on wing’s of the wind from village to village and from neighborhood to neighborhood for miles away; and during the first two or three days preceding the play, hundreds of Indians the old, the young, the gay, the grave of both sexes, in immense concourse, were seen wending their way through the vast forests from every point of the compass, toward the ball-ground; with their ponies loaded with skins, furs, trinkets, and every other imaginable thing that was part and parcel of Indian wealth, to stake upon the result of one or the other side.

On the morning of the appointed day, the players, from seventy-five to a hundred on each side, strong and athletic men, straight as arrows and fleet as antelopes, entirely in a nude state, excepting a broad piece of cloth around the hips, were heard in the distance advancing toward the plain from opposite sides, making the heretofore silent forests ring with their exulting songs and defiant hump-he! (banter) as intimations of the great fats of strength and endurance, fleetness and activity they would display before the eyes of their admiring friends. The curiosity, anxiety and excitement now manifested by the vast throng of assembled spectators were manifested on every countenance. Soon the players were dimly seen in the distance through their majestic forests, flitting here and there as spectres among the trees. Anon they are all in full view advancing from opposite sides in a steady, uniform trot, and in perfect order, as if to engage in deadly hand to hand conflict; now they meet and intermingle in one confused and disorderly mass interchanging friendly salutations dancing and jumping in the wildest manner, while intermingling with all an artillery of wild Shakuplichihi that echoed far back from the solitudes of the surrounding woods.

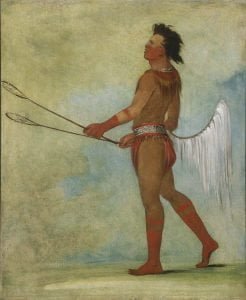

Then came a sudden hush a silence deep, as if all Nature had made a pause the prophetic calm before the bursting storm. During this brief interval, the betting was going on and the stakes being put up; the articles bet were all placed promiscuously in one place, often forming a vast conglomeration, of thing’s too numerous to mention, and the winning side took the pile. This being completed, the players took their places, each furnished with two kapucha (ball-sticks), three feet long, and made of tough hickory wood thoroughly seasoned. At one end of each ka-puch-a very ingenious device, in shape, and size, very similar to that of the hand half closed, was constructed of sinews of wild animals, in which they caught and threw the ball. It was truly astonishing with what ease and certainty they would catch the flying- ball in the cups of the sticks and the amazing distance and accuracy they would hurl it through the air. In taking their places at the opening of the play, ten or twenty, according to the number of players engaged, of each side were stationed at each pole. To illustrate, I will say, ten of the A. party and ten of the B party were placed at pole C.; and ten of the B. party and ten of the A. party at pole D. The ten of the B party who were stationed at the pole C. were called Fa-lo-mo-li-chi (Throw-backs); and the ten of the A. party also stationed at pole C. were called Hat-tak fa-bus-sa (Pole men), and the ten of the A. party stationed at the pole D. were called Fala molichi, and the ten of the B. party stationed at the pole D., Hattak fabussa. The business of the Falamolichi at each pole was to prevent, if possible, the ball thrown by the opposite party, from striking the pole C.; and throw it back towards the pole D. to their own party; while that of the Hattak fabussa at pole C. was to prevent this, catch the ball themselves, if possible, and hurl it against the pole C., and the business of the Fala molichi and Hattak fabussa at the pole D. was the same as that at the pole C. In the centre, between the two poles, were also stationed the same number of each party as were stationed at the poles, called Middle Men, with whom was a chief “Medicine man,” whose business was to throw the ball straight up into the air, as the signal for the play to commence. The remaining players were scattered promiscuously along the line between the poles and over different portions of the playground.

All things being ready, the ball suddenly shot up into the air from the vigorous arm of the Medicine Man, and the wash-o-ha (playing) began. The moment the ball was seen in the air, the players of both sides, except the Falamolichi and Hattak fabussa, who remained at their posts, rushed to the spot, where the ball would likely fall, with a fearful shock. Now began to be exhibited a scene of wild grandeur that beggared all description. As there were no rules and regulations governing the manner of playing nor any act considered unfair, each of course, acted under the impulse of the moment regardless of consequences.

They threw down and ran over each other in the wild excitement and reckless chase after the ball, stopping not nor heeding the broken limbs and bruised heads or even broken neck of a fallen Player. Like a herd of stampeded buffaloes upon the western plains, they ran against and over each other, or any thing else, man or beast, that stood in their way; and thus in wild confusion, and crazed excitement they scrambled and tumbled, each player straining every nerve and muscle to its utmost tension, to get the ball or prevent his opponent, who held it firmly grasped between the cups of his trusty kapucha, from making a successful throw; while up and down the lines the shouts of the players “Falamochi! Falamochi!” (Throw it back! Throw it back) as others shouted Hokli! Hoklio! (Catch! Catch!) The object of each party was to throw the ball against the two upright pieces of timber that stood in the direction of the village to which it belonged; and, as it came whizzing through the air, with the velocity comparatively of a bullet shot from a gun, a player running at an angle to intercept the flying ball, and when near enough, would spring several feet into the air and catch it in the hands of his sticks, but ere he could throw it, though running at full speed, an opponent would hurl him to the ground, with a force seemingly sufficient to break every bone in his body and even to destroy life, and as No. 2 would wrest the ball from the fallen No. 1 and throw it, ere it had flown fifty feet, No. 3 would catch it with his unerring kapucha, and not seeing, perhaps an opportunity of making an advantageous throw, would start off with the speed of a deer, still holding the ball in the cups of his kapucha pursued by every player.

Again was presented to the spectators another of those exciting scenes, that seldom fall to the lot of one short lifetime to behold, which language fails to depict, or imagination to conceive. He now runs off, perhaps, at an acute angle with that of the line of the poles, with seemingly super-human speed; now and then elevating above his head his ka pucha in which safely rests the ball, and in defiant exultation, shouts, “hump-he! hump-he!” (I dare you) which was acknowledged by his own party with a wild response of approval, but responded to by a bold cry of defiance from the opposite side. Then again all is hushed and the breathless, silence is only disturbed by the heavy thud of their running-feet. For a short time he continues his straight course, as if to test the speed of his pursuing opponents; then begins to circle toward his pole. Instantly comprehending his object, his running friends circle with him, with eyes fixed upon him, to secure all advantages given to them by any strategic throw he may make for them, while his opponents are mingled among them to defeat his object; again he runs in a straight line; then dodges this way and that; suddenly he hears the cry from some one of his party in the rear of the parallel running throng, who sees an advantage to be gained if the ball was thrown to him, “Falamolichi”! “Falamolichi”! He now turns and dashes back on the line and in response to the continued cry “Falamolichi”! Hurls the ball with all his strength; with fearful velocity it flies through the air and falls near the caller; and in the confusion made by the suddenly turning throng, he picks it up at full speed with his kapucha, and starts toward his pole. Then is heard the cry of his hattak fabussa and he hurls the ball toward them and, as it falls, they and the throw-backs stationed at that pole, rush to secure it; and then again, though on a smaller” scale, a scene of wild confusion was seen scuffling, pulling, pushing, butting unsurpassed in any game ever engaged in by man. Perhaps, a throw-back secures the ball and starts upon the wing, in the direction of his pole, meeting the advancing throng, but with his own throw-backs and the pole-men of his opponents at his heels; the latter to prevent him from making a successful throw and the former to prevent any interference, while the shouts of “Falamolichi!”” “Fala molichi!” arose from his own men in the advancing runners. Again the ball flies through the air, and is about to fall directly among them, but ere it reaches the d ground many spring into the air to catch it, but are tripped and they fall headlong to the earth. Then, as the ball reaches the ground again is brought into full requisition the propensities of each one to butt, pull, and push, though not a sound is heard, except the wild rattling of the kapucha, that reminded one of the noise made by the collision of the horns of a drove of stampeding Texas steers. Oft amid the play women were seen giving water” to the thirsty and offering words of encouragement; while others, armed with long switches stood ready to give their expressions of encouragement to the supposed tardy, by a severe rap over the naked shoulders, as a gentle reminder of their dereliction of duty; all of which was received in good faith, yet invariably elicited the response “Wah!” as an acknowledgement of the favor.

From ten to twenty was generally the game. Whenever the ball was thrown against the upright fabussa (poles), it counted one, and the successful thrower shouted; “Illi tok,” (dead) meaning one number less; oft accompanying the shout by gabbing vociferously like, the wild turkey, which elicited a shout of laughter from his party, and a yell of defiance from the other. Thus the exciting-, and truly wild and romantic scene was continued, with unabated efforts on the part of the players until the game was won. But woe to the inconsiderate white man, whose thoughtless curiosity had led him too far upon the hetoka. (ball ground) and at whose feet the ball should chance to fall; if the path to that ball was not clear of all obstructions, the 200 players, now approaching with the rush of a mighty whirlwind would soon make it so. And right then and there, though it might be the first time in life, he became a really active man, if the desire of immediate safety could be any inducement, cheerfully inaugurating proceedings by turning a few double summersets, regardless as to the scientific manner he executed them, or the laugh of ridicule that might be offered at his expense; and if he escaped only with a broken limb or two, and a first-class scare, he might justly consider himself most fortunate. But the Choctaws have long since lost that interest in the ball-play that they formerly cherished in their old homes east of the Mississippi River. Tis true, now and then, even at the present day, they indulge in the time honored game, but the game of the present day is a Lillipution a veritable pygmy-in comparison with the grand old game of three quarters of a century ago; nor will it be many years ere it will be said of the Choctaw tohli, as of ancient Troy Ilium fuit.”

To any one of the present day, an ancient Choctaw ball-play would be an exhibition far more interesting, strange, wild and romantic, in all its features, than anything ever exhibited in a circus from first to last excelling it in every particular of daring feats and wild recklessness. In the ancient ball-play, the activity, fleetness, strength and endurance of the Mississippi Choctaw warrior and hunter, were more fully exemplified than anywhere else; for there he brought into the most severe action every power of soul and body. In those ancient ball-plays, I have known villages to lose all their earthly possessions upon the issue of a single play. Yet, they bore their misfortune with becoming grace, and philosophic indifference and appeared as gay and cheerful as if nothing of importance had occurred. The education of the ancient Choctaw warrior and hunter consisted mainly in the frequency of these muscular exercises which enabled him to endure hunger, thirst and fatigue; hence (they often indulged in protracted fasting, frequent foot races, trials of bodily strength, introductions to the war path, the chase and their favorite Tolih.

They also indulged in another game in which they took great delight, called Ulth Chuppih, in which but two players could engage at the same time; but upon the result of which, as in the Tolih, they frequently bet their little all. An alley, with a hard smooth surface and about two hundred feet long, was made upon the ground. The two players took a position at the upper end at which they were to commence the game, each having in his hand a smooth, tapering pole eight or ten feet long flattened at the ends. A smooth round stone of several inches in circumference was then brought into the arena; as soon as both were ready, No. 1 took the stone and rolled it with all his strength down the narrow inclined plane of the smooth alley; and after which both instantly staged with their utmost speed. Soon No. 2, threw his pole at the rolling stone; instantly No. 1, threw his at the flying pole of No. 2, aiming to hit it, and, by so doing, change its course from the rolling stone. If No. 2 hits the stone, he counts one; but if No. 1 prevents it by hitting the pole of No, 2, he then counts one; and he, who hits his object the greater number of times in eleven rolling of the stone, was the winner. It was a more difficult matter to hit either the narrow edge of the rolling stone, or the flying pole, than would be at first imagined. However, the ancient Chahtah Ulte Chupih may come in at least as a worthy competitor with the pale-face Ten-pin-alley, for the disputed right of being the more dignified amusement.

Judge Julius Folsom of Atoka, Indian Territory, informed me that a friend of his, Isaac McClure, found an Ulth Chuppih ball in a mound near Skullyville, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, and not knowing what it was, brought it to him for information. This proves that the Indians who occupied the territory prior to the Choctaws also indulged in the game of Ulth Chuppih.

The following was furnished me by my learned friend H. S. Halbert, of Mississippi, a genuine philanthropist and true friend to, the North American Indian race:

“The Great Ball Play and Fight on Noxubee” (a corruption of the Choctaw word Nakshobih, a peculiarly. offensive odor), between the Creeks and Choctaws.

“In the fall of 1836, there died in the southern part of Noxubee County an aged Indian warrior named Stonie Hadjo. This old Indian had resided in the county for years and was very popular with the pioneers, who regarded him as an up right and truthful man. He was a Creek by birth, a Choctaw by adoption. This old warrior would often tell of a great ball play and fight which occurred between the Creeks and Choctaws in Noxubee County. This event, from date given by him, must have occurred about the year 1790.

“On Noxubee river there was anciently a large beaver pond, about which the Creeks and Choctaws had a violent dispute. The Creeks claimed it by priority of discovery, while the Choctaws asserted their right to it because it lay in their own territory. As the fur trade at Mobile and Pensacola, (corruption of the Choctaw words puska Okla., bread people, then small places, but the main points of trade for the southern Indians) was lucrative, each party was loath to renounce the right to the beavers. The two Nations finally agreed to settle the matter by a ball-play. A given number of the best players were accordingly selected from each Nation, who was to decide, by the result of the game, to which Nation, the exclusive right to the beaver pond should belong. Great preparations were made by each party for this important event. They commenced preparing on the new moon and it took them two whole moons and until the full of the third to complete preparations. Great quantities of provisions had to be procured, and the ball players had to subject themselves meanwhile to the usual requirement of practice, the athletic exercises customary on such occasions.

“Finally the day came, and Stonie Hadjo said that there were ten thousand Indians, Creeks and Choctaws, camped around the ball ground on Noxubee River. The Creek Chief who held the highest command, after seems his people properly encamped left to pay a visit of ceremony to great Chief of the Choctaws, who lived at some distantance. Stonie Hadjo-give the names of those two chiefs, but these names cannot now be recalled.” (If I mistake not, the Choctaw Chief was Himakubih, now to kill). “Every thing being now ready the play commenced, and it was admitted on all sides to have been the closest and most evenly matched game ever witnessed by either nation. Fortune vascillated from Creek to Choctaws and then from Choctaw to Creek. At last, it was a tied game, both parties standing even. One more game remained to be played which would decide the contest. Then occurred a long and terrible struggle lasting for four hours. Every Creek and every Choctaw strained himself to his utmost bent. Finally after prodigious feats of strength and agility displayed on both sides, fortune at last declared in favor of the Creeks. The victors immediately began to shout and sing! The. Choctaws were greatly humiliated. At length a high spirited Choctaw player, unable longer to endure the exultant shouts of the victorious party, made an insulting remark to a Creek player. (Who, in retaliation, Choctaws state, threw a petticoat on the Choctaw the greatest insult that can be offered to an Indian). The latter resented it, and the two instantly clutched each other in deadly combat. The contagion spread, and a general fig lit with sticks, knives, guns, tomahawks and bows and arrows, began among the ball players. Then warriors from each tribe commenced joining in the fight until all were engaged in bloody strife.

“The fight continued from an hour by the sun in the evening- with but little intermission during the night, until two hours by the sun the next morning. At this juncture the great chiefs of the Creeks and the Choctaws arrived upon the ground and at once put a stop to the combat, runners-having been dispatched at the beginning of the fight to these two leaders to inform them of the affair. The combatants upon desisting from the fight, spent the remainder of the day in taking care of the wounded; the women watching over the dead, The next” day the dead were buried; their money, silver ornaments, and other articles of value being deposited with them in their graves. The third day a council convened. The Creek and the Choctaw chiefs made “talks” expressing their regrets that their people should have given way to such a wild storm of passion resulting in the death of so many brave warriors. There was no war or cause for war between the two Nations and they counseled that all forget the unhappy strife, make peace and be friends as before. This advice was heeded. The pipe of peace was smoked; all shook hands and departed to their homes.

“Stonie Hadjo stated that five hundred warriors were killed outright in this fight and that a great many of the wounded afterward died. The Creeks and Choctaws had had several wars with each other, had fought many bloody battles, but that no battle was so disastrous as this fight at the ball ground. For many long years the Creeks and Choctaws looked back to this event with emotions of terror and sorrow. For here, their picked men, their ball players, who were the flower of the two Nations, almost to a man perished. Scarcely was there a Creek or Choctaw family, but had to mourn the death of some kinsman slain. For several years the Creeks made annual pilgrimages to this ball ground to weep over the graves of their dead. The Choctaws kept up the Indian custom much longer. Even down to the time of their emigration in 1832 they had not ceased to make similar lamentations.

“After the fight, by tacit consent, the beaver pond was left in the undisputed possession of the Choctaws; but it is said that soon afterwards, the beaver entirely abandoned the pond. According to Indian superstition, their departure was supposed to have some connection with the unfortunate fight.

“In 1832, a man named Charles Dobbs settled on this ball and battle ground. Stonie Hadjo, who was then living in the vicinity pointed out to him many of the graves, where in money and other valuables were buried. Dobbs dug down and recovered about five hundred dollars in silver, and about two hundred and fifty dollars worth of silver ornaments.

“This ground is situated on the eastern banks of Noxu-bee River, about five miles west of Cooksville and about two hundred yards north of where Shuqualak (corruption of Shoh-pakalih, Sparkling,) creek empties into Noxubee. The beaver pond now drained and in cultivation, is situated on the western, bank of Noxubee, about half a mile north of the ball-ground.

Frequently disputes between the ancient Choctaws and Muscogees arose as a result of a ball-play, but which too frequently terminated in a fearful fight, followed by a protracted war. My friend, H. S. Halbert, informed me by letter, of another, which was told to him by an aged Choctaw who remained in Mississippi with others at the time of the Choctaw exodus in 1832. Is as follows:

“The war in 1800 between the Choctaws and Creeks had its origin in a dispute about the territory between the Tombigbee and Black Warrior rivers, which both Nations claimed. It was finally agreed to settle the matter by a ball-play. The play occurred on the west bank of the Black Warrior, a mile below Tuscaloosa. The Creek chief was named Tus-keegee, the Choctaw, Luee, (corruption of La wih, being equal). Both parties claimed the victory. A violent dispute arose which resulted in a call to arms followed by a furious battle in which many were killed and wounded on both sides, but the Choctaws were victorious. This occurred in the spring. The Choctaws after the fight withdrew to their homes. The Creeks, stung by defeat, invaded x the Choctaw Nation in the ensuing fall under Tuskeegee and fought the second battle in the now Noxubee County, in which the Creeks were victorious. Luee again commanded the Choc taws.” But the Choctaws being reinforced, another battle was soon after fought in which the Choctaws under Himar-kubih, were victorious and drove the Creeks out of their country. I have been told that previous to our civil war the trees still showed signs of the ancient conflict.