The contest between the New England colonists and the Indians, which begun in 1722, and concluded in 1725, was called “Lovewell’s War,” from Captain John Lovewell, of Dunstable, being the principal English commander engaged in it. Although the English had purchased the greater portion of the land they occupied, the Indians, instigated by the French, would not acknowledge their title. The colonial government were anxious to avoid a war, and endeavored to settle the difficulties at conferences held between the two parties. Nothing would satisfy the Indians but a complete settlement of the boundaries. This the English governor, Shute, refused to effect, and the parties left the conferences with embittered feelings, but hostilities did not commence immediately.

The most influential of the French Jesuits, who were among the eastern tribes, was Father Halle. He had built a chapel at Norridgewock, and lived as a sort of chief ruler over the Indians of that village. That he acted as the agent of the French government, and took every occasion to excite the Indians to war against the English, is sufficiently proved by the papers captured by Colonel Westbrook, in 1722. That officer was dispatched to Norridgewock, by the government of Massachusetts, to take the Jesuit; but he escaped.

Regarding this as a new aggression, the Indians began their hostilities at once. An attack was made upon Fort George; but it failed. In revenge for this disappointment, the Indians attacked and destroyed the town of Brunswick. Massachusetts now declared war. The border garrisons were increased, and Lieutenant-governor Wentworth was active and unwearying in his efforts to place them in an efficient condition. One hundred pounds was offered for every Indian scalp which should be presented to any magistrate. Dover was attacked by the Indians, but the inhabitants nearly all escaped to the fort, and the foe retreated.

In the spring of 1724, Kingston was attacked, and four persons captured, one of whom afterwards made his escape. At Oyster Bay, some Indians were discovered lurking in the field of Moses Davis, and a company of volunteers, under Abraham Renwick, being notified of the fact, they hastened to the place, and, after Davis and his son had been killed, drove the Indians from their shelter, with the loss of three men. The remainder succeeded in making their escape.

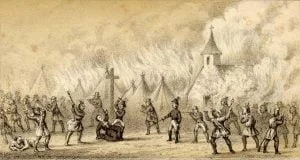

While the enemy were thus active, the colonists determined on an expedition against the Norridgewock Indians. The force which proceeded on this business, consisted of two hundred and eight men and three Mohawk warriors, and was commanded by Captains Harman and Moulton. “They came upon the village,” says Mr. Drake, “the 23d of August, while there was not a man in arms to oppose them. They had left forty of their men at Teconet Falls, which is now within the town of Winslow, upon the Kennebec, and about two miles below Waterville College, upon the opposite side of the river. The English had divided themselves into three squadrons: eighty, under Harman, proceeded by a circuitous route, thinking to surprise some in their corn fields, while Moulton, with eighty more, proceeded directly for the village, which, being surrounded by trees, could not be seen until they were close upon it. All were in their wigwams, and the English advanced slowly and in perfect silence. When pretty near, an Indian came out of his wigwam, and, accidentally discovering the English, ran in and seized his gun, and giving the war whoop, in a few minutes the warriors were all in arms, and advancing to meet them. Moulton ordered his men not to fire until the Indians had made the first discharge. This order was obeyed, and, as he expected, they overshot the English, who then fired upon them, in their turn, and did great execution. When the Indians had given another volley, they fled with great precipitation to the river, whither the chief of their women and children had also fled during the fight. Some of the English pursued and killed many of them in the river, and others fell to pillaging and burning the village. Mogg disdained to fly with the rest, but kept possession of a wigwam, from which he fired upon the pillagers. In one of his discharges, he killed a Mohawk, whose brother observing it, rushed upon Mogg and killed him; and thus ended the strife. There were about sixty warriors in the place, about one half of whom were killed.

“The famous Ralle shut himself up in his house, from which he fired upon the English; and, having wounded one, Lieutenant Jaques, of Newbury, burst open the door and shot him through the head; although Moulton had given orders that none should kill him. He had an English boy with him, about fourteen years old, who had been taken some time before from the frontiers, and whom the English reported Ralle was about to kill. Great brutality and ferocity are chargeable to the English, in this affair, according to their own account; such as killing women and children, and scalping and mangling the body of Father Ralle.”

The great reward offered for scalps, induced one John Lovewell to raise a company of volunteers, and hunt the Indians. On his first scout, he captured one Indian and got one scalp, which he brought into Boston on the 5th of January, 1725.

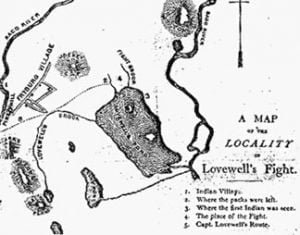

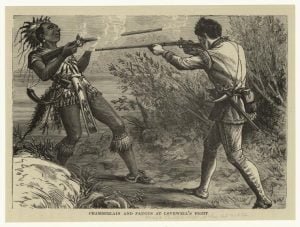

Encouraged by this success, Lovewell marched a third time; intending to attack the villages of Pigwacket, on the upper part of the river Saco, which had been the residence of a formidable tribe, and which they still occasionally inhabited. His company at this time consisted of forty-six, including a chaplain and surgeon; two of them proving lame, returned: another falling sick, they halted, and built a stockade fort on the west side of the great Ossapy pond; partly for the accommodation of the sick man, and partly for a place of retreat in case of any misfortune. Here the surgeon was left with the sick man and eight of the company for a guard. The number was now reduced to thirty-four. Pursuing their march to the northward, they came to a pond, about twenty-two miles distant from the fort, and encamped by the side of it. Early the next morning, May 8th, while at their devotions, they heard the report of a gun, and discovered a single Indian standing on a point of land, which runs into the pond, more than a mile distant. They suspected that the Indian was placed there to decoy them, and that a body of the enemy was in their front. A consultation being held, they determined to march forward, and by encompassing the pond, to gain the place where the Indian stood; and that they might be ready for action, they disencumbered themselves of their packs, and left them, without a guard, at the northeast end of the pond, in a pitch pine plain, where the trees were thin, and the brakes, at that time of the year, small. It happened, that Lovewell’s march had crossed a carrying place, by which two parties of Indians, consisting of forty-one men, commanded by Paugus and Wahwa, who had been scouting down Saco river, were returning to the lower village of Pigwacket, distant about a mile and a half from this pond. Having fallen on his track, they followed it till they came to the packs, which they removed; and counting them, found the number of his men to be less than their own: they, therefore, placed themselves in ambush, to attack them on their return. The Indian who had stood on the point, and was returning to the village, by another path, met them, and received their fire, which he returned, and wounded Lovewell and another with small shot. Lieutenant Wyman firing again, killed him, and they took his scalp. Seeing no other enemy, they returned to the place where they had left their packs, and while they were looking for them, the Indians rose and ran toward them with a horrid yelling. A smart firing commenced on both sides, it being now about ten of the clock. Captain Lovewell and eight more were killed on the spot. Lieutenant Farwell and two others were wounded: several of the Indians fell; but, being superior in number, they endeavored to surround the party, who, perceiving their intention, retreated; hoping to be sheltered by a point of rocks which ran into the pond, and a few large pine trees standing on a sandy beach. In this forlorn place they took their station. On their right was the mouth of a brook, at that time unaffordable; on their left was the rocky point; their front was partly covered by a deep bog and partly uncovered, and the pond was in their rear. The enemy galled them in front and flank, and had them so completely in their power, that had they made a prudent use of their advantage, the whole company must either have been killed, or obliged to surrender at discretion; being destitute of a mouthful of sustenance, and an escape being impracticable. Under the conduct of Lieutenant Wyman they kept up their fire, and showed a resolute countenance all the remainder of the day; during which, their chaplain, Jonathan Frie, Ensign Robbins, and one more, were mortally wounded. The Indians invited them to surrender, by holding up ropes to them and endeavored to intimidate them by their hideous yells; but they determined to die, rather than yield; and by their wild directed fire, the number of the Indians was thinned, and their cries became fainter, till, just before night, they quit their advantageous ground, carrying off their killed and wounded, and leaving the dead bodies of Lovewell and his men unscalped. The shattered remnant of this brave company, collecting themselves together, found three of their number unable to move from the spot, eleven wounded but able to march, and nine who had received no hurt. It was melancholy to leave their dying companions behind, but there was no possibility of removing them. One of them, Ensign Bobbins, desired them to lay his gun by him charged, that if the Indians should return before his death, he might be able to kill one more. After the rising of the moon, they quit the fatal spot, and directed their march toward the fort, where the surgeon and guard had been left. To their great surprise, they found it deserted. In the beginning of the action, one man, (whose name has not been thought worthy to be transmitted to posterity,) quit the field, and fled to the fort; where, in the style of Job’s messengers, he informed them of Lovewell’s death, and the defeat of the whole company; upon which, they made the best of their way home; leaving a quantity of bread and pork, which was a seasonable relief to the retreating survivors. From this place they endeavored to get home. Lieutenant Farwell, and the chaplain, who had the journal of the march in his pocket, and one more, perished in the woods, for want of dressing for their wounds. The others, after enduring the most severe hardships, came in, one after another, and were not only received with joy, but were recompensed for their valor, and sufferings; and a generous provision was made for the widows and children of the slain.