The spring of 1781 was a terrible season for the white settlements in Kentucky and the whole border country. The natives who surrounded them had never shown so constant and systematic a determination for murder and mischief. Early in the summer, a great meeting of Indian deputies from the Shawanees, Delawares, Cherokees, Wyandot, Tawas, Pottawatomie, and diverse other tribes from the north-western lakes, met in grand council of war at Old Chilicothe. The persuasions and influence of two infamous whites, one McKee, and the notorious Simon Girty, “inflamed their savage minds to mischief, and led them to execute every diabolical scheme.”

Bryant’s station, a post five miles from Lexington, was fixed upon, by the advice of Girty, as a favorable point for the first attack. About five hundred Indians and whites encompassed the place accordingly, on the 15th of August. Stratagem and assault alike failed to effect an entrance: a small reinforcement from Lexington managed to join the garrison, and the besiegers were compelled to retire on the third day, having lost thirty of their number. When Girty came forward, on one occasion during the siege, bearing a flag of truce, and proposing a surrender, he was received with every expression of disgust and contempt. His offers were spurned, and he retired “cursing and cursed,” to his followers.

The enemy were pursued, on their return, by Colonels Todd and Trigg, Daniel Boone, and Major Harland, with one hundred and seventy-six men. The rashness of some individuals of this party, who were unwilling to listen to the prudent advice of Boone, that an engagement should be avoided until a large expected reinforcement should arrive, led to their utter discomfiture. They came up with the Indians at a bend in Licking River, beyond the Blue Licks, and had hardly forded the stream when they were attacked by an overpowering force. The enemy had cut off all escape, except by recrossing the river, in the attempt to accomplish which, multitudes were destroyed. Sixty-seven of the Americans, were killed; among the number, the three principal officers, and a son of Boone.

The outrages of the indians were, soon after this, signally punished. General Clarke, at the head of a thousand men, rendezvousing at Fort Washington, where Cincinnati now stands, invaded the Indian Territory. The inhabitants fled, in terror, at the approach of so formidable an army, leaving their towns to be destroyed. “We continued our pursuit,” says Boone, who was with the army, “through five towns on the Miami River Old Chilicothe, Pecaway, New Chilicothe, Willis Towns, and Chilicothe burnt them all to ashes, entirely destroyed their corn, and other fruits, and every where spread a scene of desolation in the country.”

After hostilities between England and America had ceased, these western tribes of Indians still continued to molest the border inhabitants of the colonies. Attempts to bring about conferences failed signally in producing any marked or permanent benefit, and it was determined by the government to humble them by the force of arms.

Disastrous Campaigns Of Harmar and St. Clair

In the autumn of 1791, General Harmar marched into the Indian territories, at the head of nearly fifteen hundred men. The campaign was signally unsuccessful. The army returned to Fort Washington, dispirited and broken down, having sustained a heavy loss in men and officers, and with the mortifying consciousness of an utter failure in the accomplishment of the end in view.

Major-General Arthur St. Clair was appointed to the command of the next expedition. With a force of more than two thousand men, he marched towards the Indian settlements, and on the 3d of November, (1791,) encamped within fifteen miles of the Miami villages. On his way from Fort Washington to this point, he had built and garrisoned Forts Hamilton and Jefferson. By this reduction of his troops, and by a more extensive loss from the desertion of some hundreds of cowardly militia, he had, at the time of which we are speaking, but about fourteen hundred effective soldiers.

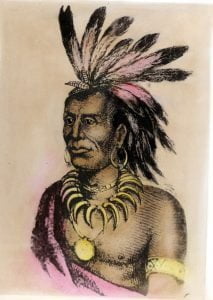

The confederate Indian tribes kept themselves perfectly informed, by their scouting parties, of all the enemy s movements, and, emboldened by recent success, prepared to give the advancing army a warm reception. The principal leader of the United Nations was the celebrated Miami chief, Michikinaqua, or Little Turtle. He was one of the greatest warriors and most sagacious rulers ever known among the red men, and he had now an opportunity for the full display of his abilities. An immense horde of fierce savages, impatient for war, was under his control, and his movements were seconded by able subordinates. Among these, the most noted were Buckongahelas, now war chief of the Delawares, and Blue-Jacket, the Shawanee. According to Colonel Stone, the great Mohawk chief, Joseph Brant, Thayendanegea, was also present, lending the assistance of his counsel and arms. Huron or Wyandot, Iroquois, Ottawa, Pottawatomie, Chippewa, Miami, Delawares, and Shawanees, with a host of minor tribes, were collected to repel the common enemy. The number of their warriors assembled on the present occasion is estimated to have been about fifteen hundred, although some have set it down at twice that force.

Before the rising of the sun, on the following day, (November 4th,) the savages fell upon the camp of the whites. Never was a more decisive victory obtained. In vain did the American general and his officers exert themselves to maintain order, and to rally the bewildered troops. The Indians, firing from covert, thinned the ranks and picked off the officers by a continuous and murderous discharge. A disorderly retreat was the result. Artillery, baggage, and no small portion of the small arms of the militia, fell into the hands of the exultant pursuers. Fort Jefferson was nearly thirty miles distant, and thither the defeated army directed its flight. The Indians followed close upon the fugitives, cutting down and destroying at will, until, as is reported, one of their chiefs called out to them to “stop, as they had killed enough!”

The temptation offered by the plunder to be obtained at the camp induced the Indians to return, and the remnant of the invading army reached Fort Jefferson about sunset. The loss, in this battle, on the part of the whites, was no less than eight hundred and ninety-four! in killed, wounded, or missing. Thirty-eight officers, and five hundred and ninety-three non-commissioned officers and privates were slain or missing. The Indians lost but few of their men, judging from a comparison of the different accounts, not much over fifty.

At the deserted camp the victorious tribes took up their quarters, and delivered themselves up to riot and exultation. General Scott, with a regiment of mounted Kentucky volunteers, drove them from the spot a few weeks later, with the loss of their plunder and of some two hundred of their warriors.

Military Operations Of General Wayne

No further important movement was made to overthrow the power of the Indians for nearly three years from this period. Negotiation proved utterly fruitless with a race of savages inflated by their recent brilliant successes, and consequently exorbitant in their demands. When it was finally evident that nothing but force could check the continuance of border murders and robbery, an army was collected, and put under the command of General Wayne, sometimes called “Mad Anthony,” in a rude style of compliment to his energy and courage, not uncommon in those times. The Indians denominated him the ” Black-Snake.”

The winter of 1793-4 was spent in fortifying a military post at Greenville, on the Miami, and another, named Fort Recovery, upon the field of St. Glair’s defeat. The last-mentioned station was furiously attacked by the Indians, assisted by certain Canadians and English, on the 30th of the following June, but without success. It was not until August, (1794,) that General Wayne felt himself sufficiently reinforced, and his military posts sufficiently strengthened and supplied, to justify active operations in the enemy s country.

Decisive Battle near the Maumee Rapids

“When the army was once put in motion, important and decisive events rapidly succeeded. The march was directed into the heart of the Indian settlements on the Miami, now called Maumee, a river emptying into the western extremity of Lake Erie. Where the beautiful stream Au Glaise empties into this river, a fort was immediately erected, and named Fort Defiance. From this post General Wayne sent emissaries to invite the hostile nations to negotiation; but the pride and rancor of the Indians prevented any favorable results. Little Turtle, indeed, seemed to forebode the impending storm, and advised the acceptance of the terms offered. “The Americans,” said he, “are now led by a chief who never sleeps: the night and the day are alike to him. Think well of it. There is something whispers me it would be prudent to listen to his offers of peace.”

The British, at this time, in defiance of their treaties with the United States, still maintained possession of various military posts at the west. A strong fort and garrison was established by them near the Miami rapids, and in that vicinity the main body of the Indian warriors was encamped. Above, and below the American camp, the Miami, and Au Glaise, according to Wayne’s dispatches, presented, for miles, the appearance of a single village, and rich cornfields spread on either side. “I have never seen,” says the writer, “such immense fields of corn in any part of America, from Canada to Florida.”

Negotiations proved futile: the Indians were evidently bent on war, and only favored delay for the purpose of collecting their full force. General Wayne therefore marched upon them and, on the 20th of the month, a terrible battle was fought, in which the allied tribes were totally defeated and dispersed. The Indians greatly out numbered their opponents, and had taken their usual precautions in selecting a favorable spot for defense. They could not, however, resist the attack of brave and disciplined troops, directed by so experienced and skilful a leader as Wayne. The fight terminated in the words of the official dispatch “under the guns of the British garrison. The woods were strewed, for a considerable distance, with the dead bodies of Indians and their white auxiliaries; the latter armed with British muskets and bayonets.”

Some days were now spent in laying waste the fields and villages of the miserable savages, whose spirit seemed to be completely broken by this reverse. By the first of January following, the influence of Little Turtle and Buckongahelas, both of whom saw the folly of further quarrels with the United States, and the hopelessness of reliance upon England, negotiations for peace were commenced, and, in August, (1795,) a grand treaty was concluded at Greenville.