Singing at ceremonies and dances was accompanied by drums and rattles of two kinds.

The large drum was made of hide stretched over a log sometimes three feet high and was used to call the townspeople together, and to accompany dancing. This in later times was replaced by a smaller type of drum, the pot-drum, didané (Fig. 32) now used at ceremonies. It was made by stretching a piece of hide over an earthen pot standing about 18 inches high, containing water. An ordinary stick was used with it as a drum stick. The hide covering was decorated usually with a painted wheel-like design, suggesting a correspondence with the cardinal symbolism (See Fig. 8, Plate IX). The black for west seems to be lacking and yellow is substituted for white in this specimen. The drum had its special resting place in front of the chief’s lodge in the town square and the privilege of beating it was vested in a certain individual.

The hand rattle, tänbané (Pl. VII, Figs. 3, 4), was formerly a gourd, but nowadays is a cocoanut shell scraped thin and filled with small white pebbles a stick being run through the nut to serve as a handle. Small circular orifices are made in the shell to let the sound out. The gourd rattle was held at right angle to the forearm in the right hand. Sun symbols (Figure 31, Nos. 23, 25), often are carved or etched around the perforations on the shell.

A characteristic and peculiar instrument is the tsonta’ (PI. VII, Figs. 10, 11) the rattles worn only by women in the dances. They are composed of six to ten terrapin shells containing small white pebbles, attached to sheets of hide. Each shell has a number of holes in it and is comparable in function to the single hand rattle. One such bunch of rattles is bound to each leg below the knee. A shuffling up and down step produces a very resonant sound from this instrument. Two women usually carry them and may cuter most of the dances when they have ht-en well started. The tsonta’ is said to he chiefly destined for the Turtle Dance, but was observed in use in others.

All of the above instruments were functionally ceremonial. There is another, however, which is strictly informal in its use. This is the flute or perhaps more properly the flageolet, lokAn’, (PI. MI, Fig. 2). It is made of cedar wood, being about two feet long and one inch in diameter. A stick of the proper thickness is split down the center and the sections gouged out until about one-eighth of an inch thick. The concave sections are then placed together in their original position and bound in five or six places with buckskin or cord. The mouthpiece is formed by simply tapering off the end abruptly. The red cedar wood used is sacred. There are six hole stops on the upper side of the lower half of the instrument. A flat piece of lead is bound with its edge at the air vent which is about four inches from the mouthpiece. The air channel to the lead is formed by the raised interior and is covered by a peculiar block of wood which is gummed and bound on. The following seven tones are produced. The pitch is about one-half a tone higher than that of the medium absolute scale.

This type of flute is one that is found widely distributed over the continent. Here as elsewhere it is employed by men as an important aid in influencing the emotions of the opposite sex. Very plaintive and touching strains are produced on the flute. They seem to have a deep effect upon the Indians, often moving the hearers to tears. Young men intentionally play these sad tunes to arouse the emotions of young girls, and the players themselves appear to be as much affected as anyone. The owner of a flute keeps his instrument wrapped up in a package and treats it with extreme care. It was formerly put to another use sometimes. When the people were traveling from a distance toward the town square to attend ceremonies there, the flute was oft”n made to give forth a few measures of music as a sort of traveling song. When passing isolated farms or settlements on the route the flute was also played to signal the presence of the travelers and to call the hearers to join them on their journey to the town square.

One of the tunes played on the flute as a love song was recorded on the phonograph and a transcription of it is offered below. The man who gave this tune exclaimed something like the following when he had finished: “Oh, if some girls were only here! When they hear that they cry and then you can fondle them. It makes them feel lonesome. I wish some were here now. I feel badly myself.”

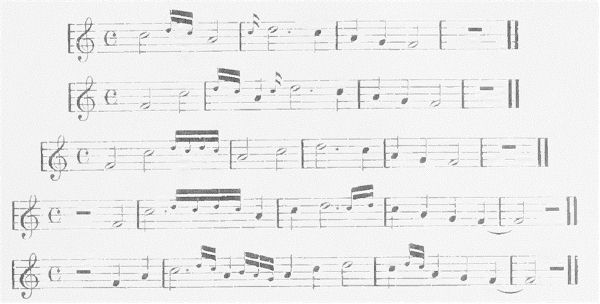

The strain is as follows:

The above theme is repeated over and over again with all possible variations, as shown in the five typical staffs given.

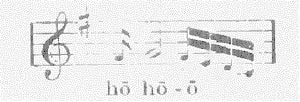

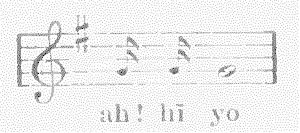

The vocal ceremonial music of the Yuchi shows one feature at least which is rather more complex than what is generally found among Indians. The character of the music of the other southeastern tribes also resembles theirs in this respect. The characteristic trait is that, in many of the ceremonial dance songs, the leader gives one measure and his followers respond in chorus in another measure or in a variation of the leader’s. It resembles what is commonly known as “round” singing where there are two members. A concrete example will, perhaps, better illustrate this point. In one of the favorite dances, the leader steps out from the lodge on the town square where his rank entitles him to sit, and walks over to the fire in the center of the square, passing around it several turns from right to left. At about the second turn he assumes a posture and rhythmic step, holds up his elbows and sings with a deep resonant voice

Before he has finished the final glide the other men, who have by this time filed in behind him, repeat the syllables on a lower note somewhere near the end of the glide, but with less of a musical tone.

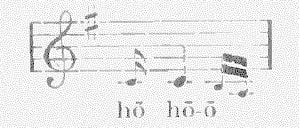

Immediately following this the leader repeats his first notes, changing the syllables to ha ha – ha. The file responds in chorus as before, changing their syllables to correspond with those of the leader. This may be repeated over again, by the leader, three or four times, sometimes varied with the syllables he he – e, then he introduces a change.

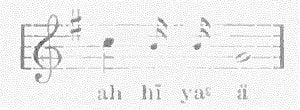

He sings

the dancers respond with

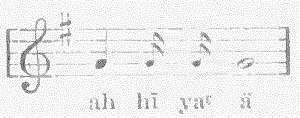

and this is repeated four tunes. Then the leader changes again. With increasing vehemence he sings

to which the dancers respond with

and this is gone through four times. The leader then gives a shorter measure,

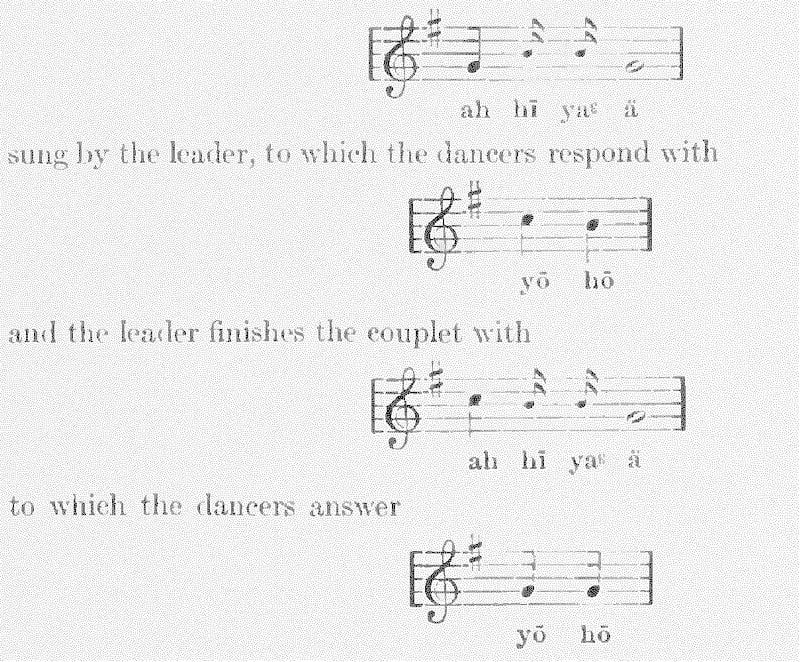

which the other dancers repeat, sounding their first note immediately after his last. The leader now, on his part, follows without a pause with

which the other dancers repeat after him. What has already been sung may constitute, with of course many fourfold repetitions, the first song of the dance and the leader closes it with a shrill yell which his followers echo. This type of song is very characteristic and common. There are, however, other ways of varying the “rounds,” either by repeating the last two syllables of the leader’s part on the same notes that he uses, or on different notes in harmony with them. Another variation has been noted in which the syllables of the hne dancers’ responses are entirely different from the leader’s. We have, for instance, in another song

Other examples of the syllables which appear in the leader’s strain and in the dancers’ responses can be seen in some of the dance songs which will be given later on.

It is characteristic of the ceremonial dance songs that they consist almost entirely of meaningless syllables. Only in rare instances do words appear for a few measures, to be lost again in the rhythmic jumble of mere syllabic sounds.

The rhythm of the songs which coincides in most dances with the beat of the drum or the shake of the rattle is predominantly one-two. The shuffling step of the dancers also accommodates itself to this time. The only other drum rhythms heard were three-fourths, four-fourths and an attempted tremolo which occurs oftentimes at the end of a song or where a break is made. Both of the rattles, the hand rattle and the woman’s terrapin shell leg rattles, are shaken in accordance with two-fourths time, either slowly or rapidly according to the circumstances. Vehemence or excitement naturally tends to increase the speed of the rhythm.

As regards the intrinsic harmony of the dance songs it must be added that to the ordinary European ear they are remarkably agreeable. The simple rhythm accented by the drum or rattle, and visualized by the steps and motions of the dancers has a noticeable canning force. To the natural voices of the Indians the songs in both tone and syllable, are well adapted.

Much practice in singing the dance songs from early youth makes the unison and promptness of the responses almost mechanical.

There is another feature of the dance songs deserving of mention here. It is a common thing for men who are clever in this hue to compose new songs, and words to go with them. They usually choose some occasion when dancing is going on to present their pieces. Naturally, of course, there is nothing radically original in either the wording or the music of the new dance songs. They are, as far as observation goes, largely plagiarized from more or less stereotyped native sources. In presenting a new piece the composer usually steps into the dancing space between dances and leads off with some familiar introduction until a few dancers have joined in behind him. Then when all are well started he begins his composition, while those behind him simply keep on with what they commenced. So the composer as dance leader carries on his new song much to the enjoyment of his consorts and the amusement of the spectators. No drumming accompanies these dances. Unfortunately full examples of this kind of musical innovation are not available in Yuchi. Such songs do not seem to have any religious bearing whatever. Their most prominent characteristics appear to be the humorous, the obscene and, in some respects, the clownish. Part of one song composition, which I remember, describes a man’s attempt to plow with a castrated hog and a bison bull harnessed together. Before the first furrow is finished, as the song goes, the hog wants to wallow in the mud and the bison bull wants a drink. Then they break out of bounds and run away, leaving the man dumbfounded. An example of obscene composition is one which alternates stanzas of meaning-less syllables, such as ya le ha’, yo ha he”, with short phrases describing cohabitation or mentioning the private parts. 1

The Indians regard a good singer and dancer as an accomplished man, hence no little pride is manifested in the art. Love songs are also common and are sung to give vent to related emotions, such as loneliness, sorrow, joy and other passions. One of these songs, which are, for the most part, also burdens without meaning, was given in a paper on the Creek Indians 2, but this might be taken for a Yuchi song as well, being apparently common to both tribes.

Citations:

- The words of another pantomimic song of the same sort in Creek have been given in “The Creek Indians of Taskigi Town.” Memoirs American Anthropological Association, Vol. II, part II, p. 138.[

]

- Ibid., p. 120.[

]