In the preceding sketches, evidences have been presented of the readiness and good judgment of the aboriginal fort builders of western New York, 1 in availing themselves of steeps, gulfs, defiles, and other marked localities, in establishing works for security or defense. This trait is, however, in no case more strikingly exemplified than in the curious antique work before us, which is called, by the Tuscaroras, Kienuka. The term Kienuka is said to mean the stronghold or fort, from which there is a sublime view. It is situated about three and a half or four miles eastward of the outlet of the Niagara gorge at Lewiston, on a natural escarpment of the ridge.

This ridge, which rises in one massy, up-towering pile, almost perpendicularly, on the brink of the river, develops itself, as we follow its course eastward for a mile or two, in a second plateau, which holds nearly a medium position in relation to the altitude of the ridge. This plateau attains to a width of a thousand yards or more, extending an unexplored distance, in the curving manner of the ridge, towards Lockport. Geologically considered, its upper stratum is the silurean limestone, which in the order of superposition, immediately overlies the red shaly sandstone at the falls. Its edges are jagged and broken, and heavy portions of it have been broken off, and slid down the precipice of red shaly under grit, and thus assumed the character of debris. Over its top, there has been a thin deposit of pebble drift 3 of purely diluvial character, forming, in general, not a very rich soil, and supporting a growth of oaks, maples, butternut, and other species common to the country. From the ascent of the great ridge, following the road from Lewiston to Tuscarora village, a middle road leads over this broad escarpment, following, apparent ly, an ancient Indian trail, and winding about with sylvan irregularity. Most of the trees appear to be of second growth; they do not, at any rate, bear the impress of antiquity, which marks the heavy forests of the country. Occasionally there are small openings, where wigwams once stood. These increase as we pass on, till they assume the character of continuous open fields, at the site of the old burying ground, orchard and play ground of the neighboring Tuscaroras. The soil in these openings appears hard, compact and worn out, and bears short grass. The burial ground is filled almost entirely with sumach, giving it a bushy appearance, which serves to hide its ancient graves and small tumuli. Among these are two considerable barrows, or small elliptic mounds, the one larger than the other, formed of earth and angular stones. The largest is not probably higher than five feet, but may have a diameter of twenty feet, in the longest direction.

Directly east of this antique cemetery, commences the old orchard and area for ball playing, on which, at the time of my visit, the stakes or goals were standing, and thus denoted that the ancient games are kept up on these deserted fields, by the youthful population of the adjacent Tuscarora village. A small ravine succeeds, with a brook falling into a gulf, or deep break in the escarpment, where once stood a saw mill, *and where may still be traced some vestiges of this early attempt of the first settlers to obtain a water power from a vernal brook. Immediately after crossing this little ravine, and rising to the general level of the plain, we enter the old fields and rock fortress of Kienuka, described in the following diagram.

To obtain a proper conception of this plan, it is necessary to advert to geological events, in this part of the country, whose effects are very striking. The whole country takes an impress, in some degree, from the great throe which worked out a passage for the Niagara, through seven miles of solid rock, severing, at its outlet, the great coronal ridge, at its highest point of elevation. Nothing, we think, is more evident to the observer, in tracing out the Kienuka plateau, than the evidences which exist of Lake Ontario having washed its northern edge, and driven its waters against its crowning wall of limestone. The fury of the waves, forced in to the line of junction, between the solid limestone and fissile sandstone, has broken up and removed the latter, till the overlying rock, pressed by its own gravity, has been split, fissured or otherwise disrupted, and often slid in vast solid masses down the ragged precipice. Kienuka offers one of the most striking instances of this action. The fissures made in the rock, by the partial withdrawal of its support, assume the size of cavern passages; they penetrate, in some instances, under other and unbroken masses of the superior stratum, and are, as a whole, curiously intersected, forming a vast reticulated area, in which large numbers of men could seek shelter and security.

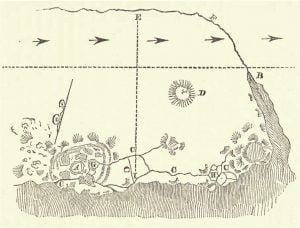

A. denotes the apex of this citadel of nature. At this point, heavy masses of the limestone, rest, in part, upon the fissures, and serve as a covering. From these primary fissures, others, marked C.C.C.C.C., proceed. The distance from G. to H. is 227 paces. The cross fissure at I., thirty-seven paces.

Most of these fissures which extend in the general parallel of the brink appear to have been narrow, and are now covered with the sod, or filled with earth and carbonaceous matter, which gives this portion of them the aspect of ancient trenches. D. denotes a small mound or barrow. E. F., a brook, dry at midsummer. B. the site of an abandoned sawmill, at the head of an ancient lake inlet or gorge. The arrowhead denotes the site of habitations, which are marked by re mains of pottery, pipes, and other evidences of the ancient, rude arts of the occupants. The parallel dots at B. mark the road, which, at this point, crosses the head of the gorge. Trees, of mature growth, occupy some portions of the brink of the precipice, extending dense ly eastward, and obscure the view, which would otherwise be commanding, and fully justify the original name. Directly in front, looking north, at the distance of seven or eight miles, extends the waters of Lake Ontario, at a level of several hundred feet below. The intermediate space, stretching away as far as the eye can trace it, east and west, is one of the richest tracts of wheat land in the State, cultivated in the best manner, and settled compactly, farm to farm. Yet such to the eye is the effect of the reserved woodlands on each farm, seen at this particular elevation, that the entire area, to the lake shore, has the appearance of a rich, unbroken forest, whose green foliage contrasts finely with the silvery whiteness of the lake beyond. It requires the observer, however, at this time, to ascend the crown of the ridge, to realize this view in all its beauty and magnificence.

Citations:

- It is not without something bordering on anachronism, that this portion of the continent is called New York, in reference to transactions not only before the bestowal of the title, in 1664, but long before the European race set foot on the continent. Still more inappropriate, however, was the term of New Netherland, i. e. New Lowland, which it bore from 1609 to 1664, many parts of the State being characterized by lofty mountains, and all having an elevation of many hundreds of feet above the sea. In speaking of these ancient periods, a title drawn from the native vocabulary would better accord with the period under discussion, if not with the laws of euphony. But the native tribes were poor generalizes, and omitted to give generic names to the land. The term of Haonao for the continent, or “island,” as they call it, occurs, but this would have no more pertinence applied to New York, than to any other portion of it. The geographical feature most characteristic of the State, is Niagara, and next in prominence, Ontario, and either would have furnished a better cognomen for the State, had they been thought of in season. But it is too late now to make the change, and even for the remote era alluded to, the name under which the country has grown great, is to be preferred. It is already the talismanic word for every honorable and social reminiscence.[

]