For a people living in quite a warm climate the Yuchi, as far back as they have any definite knowledge, seem to have gone about rather profusely clothed, but the descriptions obtained refer only to a time when the white traders’ materials had replaced almost entirely the native products.

A bright colored calico shirt was worn by the men next to the skin. Over this was a sleeved jacket reaching, on young men, a little below the waist, on old men and chiefs, below the knees. The shirt hung free before and behind, but was bound around the waist by a belt or woolen sash. The older men who wore the long coat-like garment had another sash with tassels dangling at the sides outside of this. These two garments, it should be remembered, were nearly always of calico or cotton goods, while it sometimes happened that the long coat was of deerskin. Loin coverings were of two kinds; either a simple apron was suspended from a girdle next the skin before and behind, or a long narrow strip of stroud passed between the legs and was tucked underneath the girdle in front and in back, where the ends were allowed to fall as flaps. Leggings of stroud or deerskin reaching from ankle to hip were supported by thongs to the belt and bound to the leg by tasseled and beaded garter bands below the knee. Deerskin moccasins covered the feet. Turbans of cloth, often held in place by a metal head band in which feathers were set for ornament, covered the head. The man’s outfit was then complete when he had donned his bead-decorated side pouch, in which he kept pipe, tobacco and other personal necessities, with its broad highly embroidered bandolier. The other ornaments were metal breast pendants, earrings, finger rings, bracelets and armlets, beadwork neckbands and beadwork strips which were fastened in the hair. The women wore calico dresses often ornamented on the breast, shoulders, and about the lower part of the skirt with metal brooches. Necklaces of large round beads, metal earrings and bracelets were added for ornament, and upon festive or ceremonial occasions a large, curved, highly ornate metal comb surmounted the crown of the head. From this varicolored ribbons dangled to the ground, trailing out horizontally as the wearer moved about. The woman’s wardrobe also included an outside belt, decorated with bead embroidery, short leggings, and moccasins at times.

The above articles of clothing, as can quite readily be seen, are largely of modern form if not of comparatively modern origin. However, owing to the fact that no period is remembered by the Yuchi going back of the time when these things were in use, we are left to our own resources in trying to determine which of them were native and which of them were borrowed from outsiders. If we are warranted in judging by the material used and by the form of decoration which is given them, it would seem that among the garments described, leggings, breechcloths, moccasins and perhaps shirts and turbans at least were of native type. The same, furthermore, might be said of some forms of the metal ornaments, ornamented necklaces, hair ornaments, sashes and knee bands. So far as is now known, the decorative art of the Yuchi is almost exclusively confined to the latter articles, and it may be that the antiquity of the decorative designs is paralleled by that of the objects which carry them. Reference is made in myths to the turban, woman’s skirt, man’s sash and carrying pouch with its broad bandolier in connection with one of the supernatural beings, Wind. The peculiar form of these articles as worn by him then gave the motive for the conventional decorations which are still put on such articles by the Yuchi. This, however, is to be dealt with more fully under the next heading.

The bright colored calico shirt worn next to the skin was called goci bilané, ‘what goes around the back ;’ and was provided with buttons and often a frill around the collar and at the wrists. The outer garment, goci stalé, ‘over the back,’ of calico also, was more characteristic. This had short sleeves with frilled cuff bands which came just above the frills of the under shirt, thereby adding to the frilled effect. A large turn-down collar bordered with a frill which ran all around the lapels down the front and about the hem, added further to this picturesque effect, and a great variety of coloring is exhibited in the specimens which I have seen. The long skirted coat, god staked’, worn by the old men, chiefs and town officials, was usually white with, however, just as many frills. An old specimen of Cherokee coat is shown in Pl. V, 1, which shows very well the sort of coat commonly worn by the men of other south-eastern tribes as well as the Yuchi. The material used is tanned buckskin with sewed-on fringe corresponding to the calico frills in more modern specimens. It is said that as the men became older and more venerable, they lengthened the skirts of their coats. A sash commonly held these coats in at the waist.

The breechcloth, gontsomen (Pi. V, Fig. 2), was a piece of stroud with decorated border, which was drawn between the legs and under the girdle before and behind. The flaps, long or short as they might be, are said to have been decorated with bead embroidery, but none of the specimens -preserved show it.

Leggings, to?o’, were originally of deerskin with the seam down the outside of the leg arranged so as to leave a flap three or four inches wide along the entire length. The stuff was usually stained in some uniform color. In the latter days, however, strouding, or some other heavy substance such as broadcloth, took the place of deerskin, and the favorite colors for this were black, red and blue. The outside edge of the broad flap invariably bore some decoration, in following out which we find quite uniformly one main idea. By means of ribbons of several colors sewed on the flap a series of long parallel lines in red, yellow, blue and green are brought out. The theme is said to represent sunrise or sunset and is one of the traditional decorations for legging flaps. A typical specimen is shown in Plate V, 3. The legging itself reaches from the instep to the hip on the outer side where a string or thong is attached with which to fasten it to the belt for support.

The moccasin, det?a’, still in use (Pl.V,4, and Fig. 25), is made of soft smoked deerskin. It is constructed of one piece of skin. One seam runs straight up the heel. The front seam begins where the toes touch the ground and runs along the instep. At the ankle this seam ends, the uppers hanging loose. The instep seam is sometimes covered with some fancy cloth. Deerskin thongs are fastened at the instep near the bend of the ankle with which to bind the moccasin fast. The thongs are wound just above the ankle and tied in front. Sometimes a length of thong is passed once around the middle of the foot, crossing the sole underneath, then wound once around the ankle and tied in front. This extra binding going beneath the sole is employed generally by those whose feet are large, otherwise the shoe hangs too loose. The Osages, now just north of the Yuchi, employ this method of binding the moccasins quite generally, but the moccasin pattern is quite different. The idea, however, may be a borrowed one. Yuchi moccasins have no trailers or instep flaps or lapels, the whole article being extremely plain. It seems that decoration other than the applications of red paint is quite generally lacking.

The turban, to cine, seems to have been a characteristic piece of head gear in the Southeast. The historic turban of the Yuchi was a long strip of calico or even heavier goods which was simply wound round and round the head and had the end tucked in under one of the folds to hold it. The turban cloth was of one color, or it could have some pattern according to personal fancy. Plumes or feathers were in the same way stuck in its folds for the artistic effect. That some head covering similar to the turban was known in Pre-Columbian times seems probable inasmuch as a myth mentions that Rabbit, when he stole the ember of fire from its keepers, hid it in the folds of his head dress.

The sashes, gágódi kwcné, ‘the two suspended from the both’ (PI. V, 5, 6, PL VI, 7, 8), worn by men, are made of woolen yarn. The simplest of these consists merely of a bunch of strands twisted together and wrapped at the ends. A loose knot holds the sash about the waist. But the characteristic sash of the southeastern tribes, and one much in favor with the Yuchi, is more complex in its makeup, and quite attractive in effect, the specimens I have seen being for the most part knitted. The sashes of the Yuchi seem to be uniformly woven with yarn of a dark red color. Some specimens, however show an intermixture of blue or yellow, or both. The main feature is a dark red ground for the white beads which are strung on the weft. Figures of triangles and lozenges or zigzags are attractively produced by the white beaded outlines and the conventional design produced is called ‘bull snake.’ The sash is tied about the waist so that the fixed tassels fall from one hip and the tassels at the knotted end depend from the other. Customarily the tassels reach to the knee. The sash is a mark of distinction, to a certain extent, as it was only worn in former times by full grown men. Nowadays, however, it is worn in ball games and upon ceremonial occasions by the participants in general, though only as regalia.

The woven garters, tse tSAn (PI. VI, 3), or gode’ kwcné, ‘leg suspender,’ should be described with the sash, as their manner of construction and their conventional decoration is the same. The garters or knee bands are several inches in width. They are commonly knitted, while the tassels are of plaited or corded lengths of yarn with tufts at the ends. Here the general form and colors of the decorative scheme are the same as those of the sash. The function of the knee band seems to be, if anything, to gather up and hold the slack of the legging so as to relieve some of the weight on the thong that fastens it to the belt. The tasseled ends fall half way down the lower leg.

Rather large pouches, läti’, two of which are ordinarily owned by each man as side receptacles, are made of leather, or goods obtained from the whites, and slung over the shoulder on a broad strap of the same material. It has already been said that various articles were thus carried about on the person: tobacco and pipe, tinder and flint, medicinal roots, fetishes and undoubtedly a miscellaneous lot of other things. The shoulder strap is customarily decorated with the bull snake design by attaching beads, or if the strap be woven, by weaving them in. There seems to be a variety in the bead decorations on the body of the pouch. Realistic portrayals of animals, stars, crescents and other objects have been observed, but the realistic figure of the turtle is nearly always present either alone or with the others. The turtle here is used conventionally in the same way that the bulk snake is used as the decorative theme on sashes and shoulder strap, that is, in imitation of the mythical being Wind who went forth with a turtle for his side pouch. In Pl. IX. Fig. 5, one of the chief ornamental designs is reproduced.

The next ornamental pieces to be described are the neckbands, tsutson la’, ‘bead band’ (Pl. T, 5, 6), worn by men. These are usually an inch in width and consist of beads strung on woof of horse hair; each bead being placed between two of the warps. Beadwork of this sort is widely used by the neighboring Sank and Fox and Osage and it may he that we are dealing here with a borrowed idea. Not only the idea of the neckband, but also many of the decorative motives brought out on it, may possibly be traceable to Sauk and Fox or other foreign sources. The religious interests of the Yuchi are largely concerned with supernatural beings residing in the sky and clouds, so we find many of the conventional designs on these neck-bands interpreted as clouds, sun, sunrise and sunset effects, and so on Animal representations, however, are sparingly found, while on the other hand representations of rivers, mountains, land, and earth, are quite frequent. On the whole it seems that most of the expression of the art of these Indians is to be found on their neckbands and the hair ornaments. In thus bearing the burden of conventional artistic expression in a tribe, the neckband of the Yuchi is something like the moccasin of the Plains, the pottery of the Southwest and the basketry of California.

Fastened in the hair near the crown and falling toward the back, the men used to wear small strips of beadwork, tsu’tsctsi’, ‘little bead’ (Pl. VI, 4), avowedly for ornament. They were woven like the neckband on horse hair or sinew with different colored beads. One which I collected is about eight inches long and one half an inch wide, having three-fold dangling ends ornamented with yarn. The designs on these ornaments are representative of topographical and celestial features.

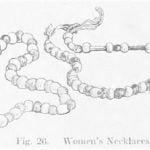

A woman’s belt, wanté galio’ndé kwené, ‘goes around woman’s waist’, is shown (Pl. VI, 1). The belts were of leather or trade cloth and had bead embroidery decorations representing in general the same range of objects as the neckbands and hair ornaments. Such belts were usually about two inches wide. Women’s dresses, nong?a’, will not be described, as they present nothing characteristic or original. Most women are found with strings of large round blue beads about their necks (Fig. 26). It is stated that necklaces of this sort have something to do with the fertility of women.

The ornaments which were made of silver alloy beaten and punched in the cold state are exceedingly numerous and varied. The use of such objects has been very general among the Indians and a general borrowing and inter-changing of pattern and shape seems to have gone on for some time during the historic period. No particularly characteristic forms are found among the Yuchi except perhaps in the breast pendants, which are generally crescent shaped, and the men’s head bands and the women’s ornamental combs. Some of these objects deserve description.

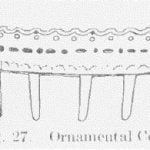

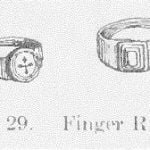

Fig. 27 shows one of the combs. The narrow band of metal is decorated with punched-in circles, ovals and toothed curves. The teeth are cut out of another strip of metal which is riveted on. The upper edge of the comb is scalloped. Women’s bracelets are shown in Fig. 28, with similar ornamentation on the body, and grooves near the edges to render its shape firm. The rings, gompadi’né, and earrings (Fig. 29) need no description. Hardly any two are alike.

We have evidence in the myths that robes, Atitcud, or hides of animals, as the name implies, were worn by the men over their shoulders. The case referred to mentions bear and wildcat skins used in this manner and it is also to be inferred that two different branches of the tribe were characterized by the wearing of bear and wildcat skins robes.

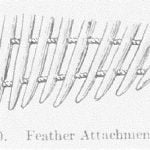

The men furthermore affect the fan, wetcá, ‘turkey’ (Pl. VII, 9), of wild turkey tail feathers. The proper possession of this, however, is with the older men and chiefs who spend much of their time in leisure. They handle the fan very gracefully in emphasizing their gestures and in keeping insects away. During ceremonies to carry the fan is a sign of leadership. It is passed to a dancer as an invitation to lead the next dance. He, when he has completed his duty, returns it to the master of ceremonies who then bestows it upon someone else. The construction of the fan is very simple, the quills being merely strung together upon a string in several places near the base (Fig. 30).

The Yuchi men as a rule allow the hair to grow long all over the head until it reaches the neck. It is then cropped off even all around and worn parted in the middle. The portrait of the old man (Pl. I) shows this fairly well. Something is usually bound about the forehead to keep the hair back from the face; either a turban, silver head band or strip of some kind. The beadwork hair ornaments used to be tied to a few locks back of the crovm. Some of the older men state that a long time ago the men wore scalp locks and reached their hair, removing all but the comb of hair along the top of the crown, in the manner still practiced by the Osage. Men of taste invariably keep the mustache, beard and sometimes the eyebrows from growing by pulling them out with their fingernails. The hair was formerly trimmed by means of two stones. The tresses to be cut were laid across a flat stone and were then sawed off, by means of a sharp-edged stone, to the desired length.

The women simply part their hair in the middle, gathering it back tightly above the ears and twisting it into a knot or club at the back of the neck. The silver combs, already described, are placed at the back near the top of the head.

Face painting, as we shall see, is practiced by both men and women for certain definite purposes. There are four or five patterns for men and they indicate which of two societies, namely the Chief or the Warrior society, the wearer belongs to. These patterns are shown in Pl. X, and will be described in more detail later on. Although the privilege of wearing certain of these patterns is inherited from the father, young men are not, as a rule, entitled to use them until they have been initiated into the town and can take a wife.

Face painting is an important ceremonial decoration and is scrupulously worn at ceremonies, public occasions and ball games. A man is also decorated with his society design for burial.

The only use ever made of paint in the case of women seems to have been to advertise the fact that they were unmarried. Women of various ages are now however, observed with paint, and it is generally stated that no significance is attached to it. One informant gave the above information in regard to the past use of paint among women and thought that to wear it was regarded then as a sign of willingness to grant sexual privileges. The woman’s pattern consists simply of a circular spot in red, about one inch across, on each cheek (Pl. X, Fig. 4). A few other objects of personal ornament which are, however, functionally more ceremonial will be described when dealing specifically with the ceremonies.