Such were the three tribes that we know once occupied the territory where the city of Chicago now stands, but in order to understand their coming and going, the history of this part of the Great Lakes region must be briefly considered.

When the accounts of the great French explorers and priests such as Champlain, La Salle, and Marquette first describe the state of the tribes, we find the Iroquois Confederacy, located in what is now the State of New York, to be the dominant military power. Archaeologists are inclined to believe that the Iroquois came to New York from the south, driving out the Algonkians, who once occupied the territory, and causing them to settle around the Great Lakes. The French found a branch of the Iroquois north of Lake Erie, whom they called the Neutrals. In 1606 Champlain found them allied with the Ottawa in fighting the Mascoutens to the west. In 1643 the Neutrals sent an expedition of some two thousand men against the “Nation du Feu,” which attacked and destroyed a palisaded village and most of its inhabitants. The latter people may have been representatives of the Potawatomi, Mascoutens, Miami, or even some of the Illinois tribes. In 1648-49 the Huron tribes were destroyed by the Iroquois, and a few years later the Neutrals were likewise conquered by them, the remnant of the tribe being assimilated by the Seneca branch of the Iroquois. Thus as early as history records we find the Great Lakes region to be the scene of war and conquest. At that time the Chicago region was apparently occupied by tribes of the Illinois, and only the archeological record can tell us who preceded them.

In 1634 Jean Nicollet met the Menominee, Winnebago, and probably the Potawatomi at Green Bay, Wisconsin. Another western war was then in progress between the former people and their allies, the Sioux, against the Chippewa. The Lake tribes very early allied themselves with the French who were the enemies of the Iroquois. In 1641, Verwyst states, the Potawatomi were living near the Winnebago. The Jesuit Relation of 1642 mentions them near Sault Ste. Marie, where they had fled to escape a hostile nation which was continually harassing them. There seems some reason to believe that the Potawatomi and the Sauk formerly lived in Michigan, and had been driven across the Straits of Mackinac by the Neutrals, who seem to be the nation referred to in the Relation. In 1667 Father Allouez met three hundred warriors of the Potawatomi at Chaquamogon Bay. In 1670 a portion of them were living on the islands in the mouth of Green Bay. From the accounts of these early French missionaries, the Menominee, Sauk, Potawatomi, Miami, Winnebago, and Mascoutens seem to have taken refuge in various villages around Green Bay, having been driven there from the south-east. Tribal boundaries do not seem at all clearly defined, and earlier wars appear to have disrupted all the tribes of the region. Only the Winnebago are referred to by Father Dablon as original owners of the territory. The collective term “Nation du Feu,” then, appears to refer not to one specific tribe, but to all those peoples that in the seventeenth century were congregated in the vicinity of Sault Ste. Marie and Green Bay.

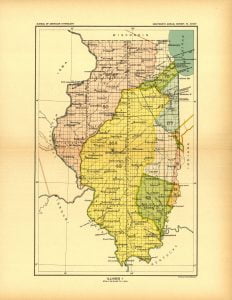

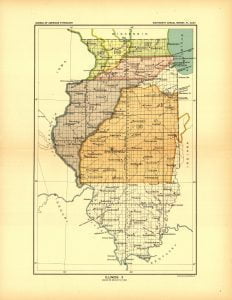

During the years 1671-72, the expatriated Hurons united many of the Ottawa, Sauk, Foxes, and Potawatomi in a raid against the Sioux with whom they were then at peace, but the allies were severely defeated. At that time some of the Miami were living with the Mascoutens near Green Bay, but shortly afterward they moved south to where in all probability the remainder of the Miami were living around the southern end of Lake Michigan. There seem to be no records of the displacement of the Illinois proper by the Miami, but Charlevoix mentions a Miami village on the site of Chicago in about 1671. Harassed by their Iroquois neighbors, the Illinois tribes seem to have congregated on the Illinois River, near Fort St. Louis, where they are mentioned by La Salle in 1684. Meanwhile the Fox, as well as the Potawatomi, were moving south along the west shore of Lake Michigan. The former, allied with the Sauk, came into violent contact with the French, and were finally crushed by Sieur De Villiers at Little Butte des Morts in 1728.

The Potawatomi, however, continued their southward movement. By the close of the seventeenth century they had displaced the Miami, and held all the territory around the southern end of Lake Michigan, one band living on the present site of Chicago.

The exact origin of the name “Chicago” is not certain. In 1721 Father Charlevoix, as has been stated, derived the name from that of the river, and it is known that about 1725 there was an Illinois chief of this name, facts that seem to point to the Illinois as the name-givers. In the Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo dialects, however, it is translated as “place of the skunk,” and the Menominee and Ojibwa have legends referring to that animal in connection with the site. The name is mentioned in connection with a Miami village in the period of the earliest explorations, between 1670 and 1700, but one is tempted to attribute the name to the Illinois who seem to have been the first historic people to live near the site, though at this late date the question is probably unanswerable.

Following this period of aboriginal warfare, of which we are only able to catch glimpses, came another long period of fighting in which the French, British, and Americans fought for a continent, and again the region here discussed was the scene of a large part of the struggle. Champlain’s early battle against the Iroquois had given the latter to Great Britain as powerful allies. In turn the majority of the Lake tribes, who feared the Iroquois, espoused the cause of France. As early as 1690 a British envoy came to Wisconsin to obtain aid from the Indians, but was unable to conclude alliances. During the French and Indian wars the Lake tribes united with the French, and under Sieur Charles de Langlade in 1795, were responsible for the crushing defeat of the British forces under General Braddock. Toward the close of the war, as the power of France was waning, Pontiac, a great chief of the Ottawa, organized a conspiracy of all the tribes against the British. All the forts save Detroit and Fort Pitt were captured, and their garrisons massacred; but the French were already defeated, and the great scheme of Pontiac was doomed to failure. Failing to stir up the tribes along the Mississippi, he finally made peace at Detroit in 1765. Later, while attending a drinking carousal at Cahokia, Illinois, he was murdered by an Indian of the Kaskaskia branch of the Illinois tribe.

This murder greatly outraged the Lake tribes, and a war of extermination was waged against the Illinois, reducing them to a pitiful handful that took refuge with the French settlers at Kaskaskia. The murder of Pontiac occurred in 1769, and by 1800 there were only a hundred and fifty Illinois alive; thus as a distinct people they fade out of history. The lands of the Illinois were taken over by the Kickapoo and Potawatomi. On the opening of the Revolutionary War the Potawatomi sided with the British, and were active from time to time against the United States, until “Mad Anthony” Wayne’s victory at Fallen Timbers and the ensuing Treaty of Greenville in 1795. The British, however, by generous trading and bribery kept the allegiance of the Lake tribes for almost half a century after the northwest territory passed out of their hands. At the time of the Treaty of Greenville the Potawatomi ceded to the United States an area six miles square located at the southern end of Lake Michigan. There, in 1804-5, Fort Dearborn was erected. Immediately following this treaty the Potawatomi notified the Miami that they intended moving down upon the Wabash River, and shortly afterward did so, driving the Miami to the north-west of that river. Thus the Potawatomi, occupying about fifty villages, were dominant in a large territory that included northern Illinois, Indiana, and part of Michigan.

Just prior to the war of 1812, Tecumseh and his brother, the Shawnee Prophet, organized a great revolt among the Mississippi tribes, but influenced by John Kinsey and the American officers at Fort Dearborn, the Lake tribes were, on the whole, inactive. General Harrison’s victory over the Prophet at Tippecanoe ended the revolt, but it was closely followed by the second war between the British and Americans. Incited by the British agents at Malden and nearby posts, the Lake tribes created havoc along the American frontier. Threatened by superior forces, Captain Heald commanding Fort Dearborn, on the site of Chicago, abandoned the fort against the advice of Winnimeg, a friendly Potawatomi chief. The ensuing massacre of a large part of the garrison followed. The Potawatomi were the tribe concerned in this well known affair, certain of the Indians distinguishing themselves by their cruelty, and others, like Black Partridge and Waubansee, by their mercy and aid to the survivors. Captain Heald, John Kinsey, about twenty-five soldiers, and the majority of the women were protected by friendly Indians, and eventually reached safety. The Potawatomi burned the fort, but at the close of the war in 1816, it was rebuilt. A sketch of Chicago as it appeared in 1820, four years later, is reproduced in Plate II. A garrison was maintained here, off and on, until December 29th, 1836, one year before the incorporation of the City of Chicago.

The close of the war of 1812 practically marked the end of the Indians’ day in the northwest territory, for with peace, the rich lands of the region began to draw settlers in ever increasing numbers. With the settlers came the military forces of the United States, now free from the threat of European interference. The Lake tribes who had formerly roamed at will now began to be driven to the west. The Blackhawk War of 1832 was the last feeble flare of opposition to the American advance, but the recalcitrant Sauk and Fox were soon crushed by overwhelmingly superior forces. In the same year the Winnebago ceded to the United States all their territory south-east of the Wisconsin and Fox Rivers. In 1833, a grand council of chiefs and headmen met at Chicago and ceded all their lands east of the Winnebago territory. The three tribes of Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Chippewa, who claimed to have once been a single people, were represented at this council, wherein they gave up all their best lands, and were assigned to various reservations. Two years later the Potawatomi came to Chicago to receive their annuities before leaving for their western reservation. About five thousand of the tribe were present, and farewell ceremonies were held on leaving this rich territory they had previously conquered by force of arms. Most of the tribe were moved to a reservation at Council Bluffs, Iowa, where we have the description of them given by Father De Smet; others fled to Canada and to their old territory in northern Wisconsin, for they feared the Sioux who were to the west of the new reservation.

The tide of settlers soon reached the five million acre reservation assigned to them in Iowa. In 1846 all those who had not fled to Canada or back to Wisconsin, were moved to a new reservation in western Kansas. There they remained until 1868, when they were again moved into the “Indian Territory” of Oklahoma. As a result, the Potawatomi are scattered from Ontario and northern Wisconsin, through Iowa and Kansas, into Oklahoma. In the former areas they maintain some of their old life, but in the other regions they have taken over the ways of their white conquerors, and many of them have become prosperous citizens.

It has been estimated that in 1918 there were 3,731 Potawatomi in the United States and 3,000 in Canada, making a total of 6,731 in all. The Department of Commerce report, in 1910, gives the total number of pure blood Potawatomi in the United States as 960, and both mixed and full bloods as 2,440. If the figures given for 1918 may be trusted, the tribe would seem to be increasing, although the 1910 report shows that a great deal of racial intermixture has taken place. In 1905, according to the Handbook of the American Indian, there were only 195 persons, mostly of mixed blood, representing the Illinois tribes. The report of 1910 does not mention the Illinois, and gives the total population of the Miami as only 226, with merely 59 persons of full blood. Clearly, of the tribes who once lived in this region, the Potawatomi alone have survived in anything like their old numbers, while the Illinois and Miami ,have come to the verge of extinction. Such were the peoples that within the brief space of written history fought and lived on the site where the city of Chicago now stands. Behind this realm of history there stretches a vast period of which we may only learn as the work of American archaeology proceeds.