After the French lost their claimed possessions upon the North American continent and were driven there from, the Chickasaws, from that time to the present, have been at peace with the world of mankind; and though they never wholly recovered from the long devastating wars with the French, yet they fully maintained their independence to the last.

Their country lay adjoining the Choctaws on the north; and, like that of the Choctaws, was as fertile and beautiful a country as the eyes of man ever looked upon; as it appeared under their own and Nature’s rule, it indeed possessed a charm that fascinated the admirers and lovers of the grand and the beautiful. There was a beauty bordering on the sublime in the spring, as nature unfolded and spread out her forest robes; also, a loveliness in the summer, with her shady hills and valleys; a quiet, too, in the calm and mellow autumn, with the variegated hues, falling leaves and tranquil scenes, which language cannot depict, or even imagination conceive. With no undergrowth whatever the great variety of majestic trees of centuries growth covered the hills and valleys; yet with the ground everywhere concealed under a thick carpet of grass one to two feet high, intermixed, especially on the prairies, with wild flowers of every shade of color, covering the face of the entire earth. In the months of April and May strawberries were found profusely scattered amid the grass of the undulating prairies that lay along the banks of their rivers and creeks, and here and there scattered amid the hills and valleys of their forests; then summer too yielded her immense store of black berries on every side; in turn, followed autumn with prodigal abundance of hickory nuts of several varieties, walnuts, pecan, buckle berries, wild plums, persimmons, wild grapes, muscadines, all of excellent flavor; while from early spring to late autumn, among the wide extended branches of the forest trees high above the verdant carpet of green that lay spread out beneath by the accomplished hand of nature, their forest orchestra, unsurpassed by the art of man, filled the groves with melody and rivaled, with their bright and variegated plumage, the hues of the flowers that bloomed beneath, seemingly but u to waste their sweets upon the desert air. The scene seemed indeed as if the hand of enchantment had suddenly raised a forest on the bosom of a primitive prairie.

There amid those magnificent parks of primitive nature, deer in great numbers, grazed with their cattle and horses, while everywhere could be seen flocks of wild turkeys feeding under the forest trees whose tops, seemed alive with jolly squirrels, all undisturbed only as the swift arrow from the noiseless bow or the deadly bullet from the unerring rifle demanded food for the Chickasaw; while the vast canebrakes along all the water courses abounded with carnivorous animals of various kinds in great numbers, furnishing skins and furs to supply the necessities of the lords who justly claimed dominion over those vast solitudes and their various quadruped occupants, and who were as noble a race of unlettered men and women as ever lived upon earth; wholly free by fortunate ignorance from the thousand debasing and ruinous vices.

But to one who has witnessed all the changes which have taken place in the native characteristics of the southern Indians in their former independence and happiness, as also in the appearance of their ancient domains since their first settlement by the White Race, all seem as a dream of the night or romance of the imagination; and he finds it difficult to realize the features of that forest wilderness which was the home of his boyhood days, alike with that of the red man. The humble little cabins of the generous and hospitable Indians, their little fields of corn, pumpkins, potatoes and beans that furnished their supplies of bread, etc., have long since been swallowed up in the wide-extended group of the cotton fields of civilization, and the vast forests have disappeared, leaving no trace of their former loveliness; and when he reflects on their original aspect, his thoughts seem to revert to a period of time greatly more remote than it really is; and the view from one extreme to the other appears as that of an opposite shore over a wide expanse of water, whose hills, valleys and forests present a confused but romantic scenery, losing itself in the distant horizon, though doubling the retrospect of life; and did not the definite number of his years teach him the contrary, he would imagine himself much older than he really is. But how different it must be with those who have passed their lives amid cities and ancient settlements, where the same unchanging aspect presents itself from year to year. There the years come and go with no striking events or great changes to mark their different periods, and give them an imaginary distance from each other, and life passes away as an illusion or dream, to close in bitter murmurings of its shortness.

A few years after the exodus of the Chickasaws and Choctaws, and before the tide of white emigration had set in the most prominent feature of their forsaken country was its profound solitude, even the days seeming more solitary than the nights; nor did the gobbling of the wild turkey, the chattering of the squirrel, the chirping of a bird, mingling with the tapping of the woodpecker upon the hollow limb of a decaying tree, seem to enliven the silent and lonely scene; and he who roamed through the solitudes of the forests, as bequeathed to the White Race by the Chickasaws and the Choctaws in 1830, was truly alone and far away from the din of civilized and domesticated life. The fading rays of the declining sun received not the requiem of the song of the laborer returning from his toil; but its silence was interrupted by the howl of the wolf and the cry of the panther issuing from the canebrakes in quest of their prey upon the highlands; nor were his returning rays on the morn announced by the voice of the domestic cock, but by the hoot of the owl as he sought the deeper solitudes of the dark swamp to doze away the unwelcome light of day.

Though such a hunters paradise will never be found again upon the North American continent; yet hunting alone was not wholly free of danger, and though the hunter was seldom without his dog, the true and faithful animal to man of the brute creation, whose native sagacity taught him to be as watchful as Argus and who saw everything and heard every sound, and the acuteness of whose scent gave warning of all approaching enemies, yet when in eager pursuit of his game, with hope and fear alternately predominating in his breast, his path was sometimes beset with hidden enemies. Under his footsteps the sluggish, yet spiteful, rattle snake, then abundant, might be coiled in watchfulness to inflict a deadly wound upon all intruders into his retreat; Or the wily panther stretched upon the limbs of a tree might suddenly drop from his perch upon him to dispute the right of man s supremacy over the brute creation, as also his cousin, the catamount, which, in those early days, not infrequently tried his physical strength with man, though he paid dearly for his temerity, since his sharp teeth and keen claws proved of little avail against the long, keen-edged knife wielded by the hand of the sturdy hunter; though the latter al ways bore, as trophies of his victory, the unmistakable evidence of his enemy s valor.

When watching at a deer lick at night by the light of the full orbed moon, in which the writer has indulged years ago in the Mississippi forests then untouched by the ax, the hunter found as his rival in the same sport, the panther or the catamount, sometimes both; and whose presence was made known by the moving shadow cast upon the ground by moon-light as he was preparing to leap from his perch upon a deer that had, unconscious of danger, walked into the lick. An incident of this kind happened to a hunter in Oktibbihaw County, Mississippi, shortly after the exodus of the Choctaws. He had found a deer lick in Catarpo (corruption of the Choctaw word Katapah, stopped referring to the obstructions in the creek by drifts) swamps, which was much frequented by the deer. He built a scaffold 15 or 20 feet high on the edge of a lick, and on a beautiful night of the full moon, shortly after sundown, took his seat thereon. About 10 o’clock at night a deer noiselessly entered the lick a few rods distant from his place of concealment, and, began licking the salty earth; he was just in the act of shooting it, when his attention was attracted from the deer to a moving shadow upon the ground between him and the deer, he at once looked up to ascertain who his neighbor was, and was not a little surprised to see a huge panther standing” on a projecting limb of a tree, that reached nearly over and just behind him, and preparing to spring upon the unsuspecting deer. He thought no more of the deer, and gave his undivided attention to his rival who had unceremoniously and clandestinely taken his seat a little higher and nearly over his head without so much as saying “By your leave.” Not being very fastidious just then, he quietly yielded the right of precedence to his fellow hunter above, in all things pertaining to the deer quietly licking the salty earth below. For several minutes he gazed upon, the huge beast as it maneuvered upon the limb seemingly doubtful as to making a successful spring. Finally the panther made a tremendous leap from the limb, passing almost directly over the hunter s head, and lit directly upon the deer s back. The bleating of the helpless deer momentarily broke the stillness of the forest, and then all was hushed. The panther pulled his victim to the outer edge of the lick, stood a moment and then with mighty bounds disappeared in the surrounding forests. During all this the hunter sat quietly upon his perch cogitating over the novel scene. But his reveries were suddenly interrupted by a wild and terrible yell, seemingly half human and half beast, fearful enough to awaken all the denizens of the forest for miles away; then came an immediate response from a distant point in the swamp. That was enough to bring the hunters cogitations to a fixed determination, which was clearly manifested by the agility displayed in descending the scaffold, and the schedule time on which: he ran towards home, leaving the two panthers to enjoy their unenvied supper of venison in their native woods undisturbed. Often the hunter found the panther had preceded him at the deer-licks; in all such cases, having previously resolved never to dispute precedency with any gentleman of that family, he quietly left him to the undisputed, possession of the chance of venison for that night particularly.

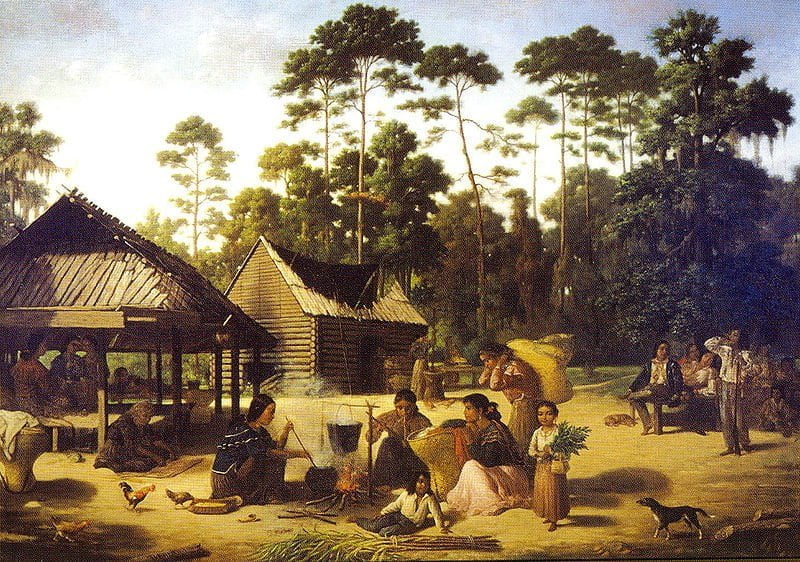

The Chickasaws, at the time the missionaries were established among them, as the Choctaws and other southern tribes, lived in rude log houses provided with a few culinary articles (all they desired), and with skins and furs, elaborately dressed and finished, for their bedding; all of which were principally made by the women, who were equally skilled in the art of making earthenware for all domestic purposes, as they were proficient in the art of preparing the skins and furs of various animals for domestic use, which their forests so bountifully supplied. Their shoes, called moccasins, were principally made of the skins of deer thoroughly dressed by a process, unequalled by the art of the whites, and beautifully ornamented with little Treads of various colors.

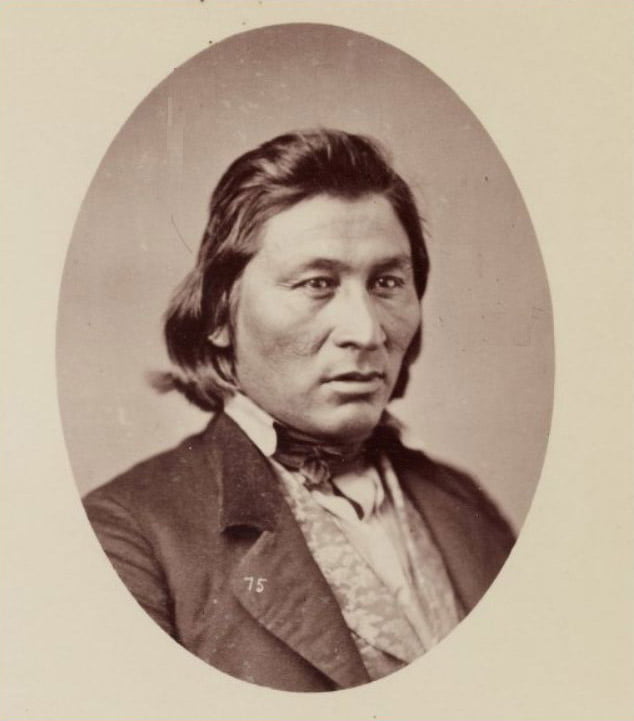

As ornaments, the men wore four or five broad crescents of tin highly polished, or of silver when to be obtained, suspended upon the breast, one above the other, and one around the head. They also used little beads in ornamenting their leather garments, intermingled with fancy embroidery. Their favorite embellishment, as with all North American Indians, was the vermilion paint with which they decorated their faces. This mode of decoration was confined to the men.

The women, as their white sisters, wore ornaments suspended from their ears, bracelets around their necks, and also strings of various kinds of gaudy beads.

The ancient Chickasaws were deservedly celebrated for their handsome young women; and seldom have I looked upon such specimens of female grace and loveliness as I have seen among the Chickasaws three quarters of a century ago in. their former homes east of the Mississippi river, nor do they fall much below at the present day. Their eyes were dark and full and their countenances like their native clime always beaming with sunshine whose sympathetic smiles, chased fatigue away and changed the night of melancholy into day. They were truly beautiful and, best of all, unconsciously so. Oft was I at a loss which most to admire the graceful and seemingly perfect forms, finely chiseled features, lustrous eyes and flowing hair, or that soft, winning artlessness which was so pre-eminently theirs.

To the Chickasaws, as to all the North American Indians, worldly honors and distinctions that arose from wealth or family connections were as empty bubbles unworthy of their consideration or anxiety. Ignorant of commerce, so they were utterly ignorant of the wealth and luxuries of the civilized world, with all their attending vices, nor did they desire to know. Therefore, they lived in peaceful contentment and died in blissful ignorance of the empty distinction of wealth or rank; thus all were upon a natural equality; all dressed alike, and all met as equals everywhere, at all times and upon all occasions. The virtues of their primitive simplicity were indeed many. Punctuality and honesty in their dealings, and unassumed hospitality to strangers were habitual; unalloyed friendship and cordiality to their neighbors universal; and all seemed as members of one great, loving family, connected by the strongest ties of consanguinity.

The greatest care was bestowed upon their children by the Chickasaw mothers, whom they never allowed to be placed upon their feet before the strength of their limbs would safely permit; and the child had free access to the maternal breast as long- as it desired, unless the mother s health forbade its continuance. Children were never whipped by the parents, but, if guilty of any misdemeanor, were sent to their uncle for punishment (the same as the Choctaws), who only inflicted a severe rebuke or imposed upon them some little penance, or, what was more frequent, made appeals to their feelings of honor or shame. When the boys arrived at the” age of proper discrimination so considered when, arrived at the age of 12 or 15 years they were committed to the instructions of the old and wise men of the village, who, at various intervals, instructed them in all the necessary knowledge and desired qualifications to constitute them successful hunters and accomplished warriors. As introductory lessons they were instructed in the arts of swimming, running, jumping, wrestling, using the bow and arrow; also, receiving from those venerable tutors those precepts of morality which should regulate their conduct when arrived at manhood. The most profound respect (a noted characteristic of the North American Indians) was paid everywhere to the oldest person in every family, whether male or female, and whose decisions upon all disputed points were supreme and final, and were received with cheerful and implicit obedience. No matter how distant their blood relations might be, all the members of a family addressed its head as father or mother, as the case might be; and whenever they meant to speak of him (their natural father), they said, “My real father,” in contradistinction to that of father applied to the chief or head of the family.

The itinerant white trader, with his smuggled whiskey, was, has ever been, is and will ever be, the patent instrument in the hands of the devil of demoralization among all Indians, and counteracted the moral and religious influence, teachings and regulations of the missionaries of the long ago, as well as of the present day. Still those devoted teachers of righteousness of the long past succeeded ineffectually removing forever many of their ancient superstitious customs and beliefs in almost and incredible short space of time. The power and influence of the “Medicine Man,” the magic power of their personal totems, and alike that of the Rain Maker, the Prophet, soon vanished before the light of the Gospel of the Son of God, as mists before the/morning sun; and it was truly affecting to witness with what deep and unfeigned interest they listened to the history of the Cross, as narrated by those true and devoted servants of God, seventy-five years ago; and how soon, under the Divine guidance, they seemed to comprehend and feel the regenerating influence of revealed religion. With unfeigned astonishment they, heard the story of the atonement. For a man to yield his life to the demands of a violated law for the life he had taken, or that a friend might die for a friend, was their own law and creed; but for one to voluntarily die for a known and inveterate enemy yea, for the Son of the Great Spirit to willingly die for those who despised and reviled him required more than the logic and eloquence of the missionaries could accomplish; but it pleased the Divine Spirit to enlighten their understandings, and they soon manifested an earnest faith clearly visible in their prayers, daily walk and conversation and in their lives and deaths. Thus God himself proved the whites that the live Indian was as good as the live white man, and in many respects better.

As the art of writing was unknown to the Chickasaws, before the advent of the missionaries among them; their history rested alone upon tradition, in common with the Indian race, handed down through succeeding generations; and that a correct, truthful and enduring knowledge of their traditional love might be imparted to each generation, as, in turn, it took its place upon the stage of life, and which each was taught to regard as sacred and to cherish with the greatest fidelity, that, in their turn, they might also be able to transmit it to their successors with the exact minute ness they had received it, the young men, as the future repositories of the past, were, at various intervals, summoned before the aged patriarchs of the Nation to have rehearsed to them the sacred things in which they had been previously instructed, and which were soon to be wholly entrusted to their care, that it might be ascertained whether there would be found any omissions from forgetfulness, or additions proceeding from nights of youthful fancy, or the prurience of invention; thus evincing a regard for historical narrators highly commendable and worthy of imitation by all recorders of events.