One of the several arguments that Southeastern archaeologists have used to dismiss a direct cultural connection between the Southeastern United States and Mesoamerica is that architecture of the respective regions was different. 1 The architecture of the largest and most sophisticated Maya cities WAS more sophisticated and larger scaled than in towns in the Southeast, but the same architectural elements could be found in both regions. The Mesoamerican pyramids were really earthen mounds veneered with stone in some civilizations, left as clay stuccoed mounds in others.

The temples in both regions mimicked earlier residential structures that sat on the earliest platform mounds in both regions. Stone structures have been recently identified in several town sites in northern Georgia. Stone veneered mounds are also found in that region. Meanwhile, earthen pyramids are quite common in northern Mexico and along the Gulf Coast in regions, where there are few surface stones.

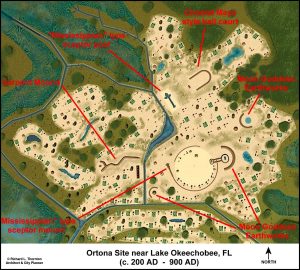

The U-shaped ball courts at Ortona and in several other locations in Georgia are very similar to the U-shaped ball courts of Tabasco State, lowland Chiapas and southern Vera Cruz.

Shells were used in lieu of stones for veneering several structures at Ortona and many other towns in Southern Florida. This practice was also utilized along the coast of Mexico and northern South America.

Lime stucco

Cutting profiles through the existing terrain of the main mound, the archaeologists realized that an earlier mound had been constructed in a similar form. 2 Additional soils and a stucco of burnt lime shells and clay had been added to enlarge it. Most of the outer stucco had eroded, thus exposing the sandy soil to erode irregularly. Indeed, this was a ceremonial structure very different than others that were known.

The presence of lime stucco is highly significant. Many archaeological references state that the Southeastern Native Americans did not know how to make lime stucco and only used clay stucco. The statement is then used as one of the arguments against a Mesoamerican presence in the Southeast. This prevalent belief contradicts history and at least one archaeological site report – Ortona.

During the late 1500s, Spanish explorers observed crushed shell, lime stucco on the buildings of the Wahale (Guale in Spanish) along the coast of Georgia. 3 It was also seen upstream along the Altamaha River on the buildings of the Tamatli in the Province of Tama. In 1783, Lt. Henry Timberlake observed crushed shell-lime stucco on the houses of the Tamatli, who had joined the Cherokee Alliance. 4

The Great Temple of the moon goddess, Ixchel

The larger of the twin mounds was oval and appears to have reached its final form between 700 AD and 900 AD. 5 After 900 AD political power shifted eastward to the more compact town of Wakata. The town at Ortona continued to thrive and grow for another 250 years, but few large ceremonial structures were built there after 900 AD.

Oval mounds are very usual in the United States, except in the areas of the Southeast, once occupied by the ancestors of Creek Indians – Georgia, South Carolina, western & south central North Carolina and southeastern Tennessee. During the Late Mississippian Phase, known as the Lamar Culture in Proto-Creek regions, the largest temple in each town was typically an oval and oriented to the Summer Solstice.

There was a small oval mound (Lesser Temple Mound) built near the northeastern edge of the Great Temple Mound at Ocmulgee National Monument (Macon, GA) around 925 AD. 6 Mound B at Etowah Mounds National Landmark Cartersville, GA, a platform for a royal residence begun around 1250 AD, was also oval. However, the oval shape was not seen much otherwise until around 1375 AD, when Etalwa (Etowah Mounds) was apparently attacked and burned. Thereafter, virtually all major mounds were oval in the former Creek Homeland.

There was a large temple or royal residence on the top of the oval mound at Ortona. 7 It was supported by large timber posts, but there was no evidence of heavy exterior walls. Given the semi-tropical climate of the Lake Okeechobee region, the residents of Ortona probably preferred walls woven from canes that functioned like modern-day screened porches. This is also the case most of the other buildings studied by archaeologists at Ortona.

Among the Maya, oval shaped buildings and pyramids are typical of the Late Classic Period (750-1000 AD) in the Puuc Region of the central Yucatan Peninsula. 8 They are believed to be associated with the worship of the Moon Goddess, Ixchel or the Maya’s calendar. In addition to its symbolic meaning, an oval pyramid is much more resistant to erosion and earthquake stress, since the stucco has no orthogonal edges unequally subject to blowing rain, and tectonic (earthquake) stresses on the structure are equally distributed. Possibly, the ancestors of the Creeks adopted the oval shape as a more durable form of an earthen pyramid in addition to some symbolic meaning.

The main oval pyramid at Ortona was connected to a low, rectangular pyramid, by two perpendicular earthen causeways. 9 The symbolic or esthetic reasons for this arrangement are unknown, but the effect would be the creation of a pond within the interior of the temple. The mortuary temple complex at Fort Center, Florida also had a small pond within its interior. 10

In the drought-prone northern Yucatan Peninsula, there are very few surface streams. Many Maya rituals dedicated to the Maya rain god, Chaac-Mol were associated with natural wells, called cenotes, and man-made cisterns. However, around Lake Okeechobee, natural water resources are abundant. The ceremonial pools found in the towns around Lake Okeechobee probably had only ritualistic functions. Perhaps captured rain water, being purer, was also used for drinking and/or ritualistic purposes.

The Mayas often tossed valuable ornaments, pottery, rare animals, and even humans into their natural and manmade wells as sacrifices to the rain god. Archaeologists did find some ornamental artifacts in the basin area of the Ortona temple, but no human skeletons. 11 It is possible that the pool was the location of sacrifices, but there is little evidence to back up that postulation.

The lower mound, also shaped as an oval, truncated pyramid, was directly adjacent to a large round plaza. Ceremonies and rituals help on its top, would have been much more visible to citizens standing in the plaza. Archaeologists found evidence that open sided structures were erected on its cap. It is not known if there were always such sheds on the lower mound or if these were only erected for special occasions.

Crescent shaped mounds

Crescent shaped mounds have been found on the Gulf Coast of Mexico in association with Chontal Maya ports or settlements, but are almost non-existent in the remainder of Mexico. Those in Mexico are earthen construction as are their counterparts in Florida. Several of the Florida crescent mounds were veneered with shells in order to stabilize their surfaces and to resist erosion.

On the east side of the temple mound was a massive semi-circular earthen mound. It apparently had no flat cap on which ceremonies could have been performed, but has been so eroded that there is no way to determine, with certainty, its original form. The semi-circular shape does reveal its symbolic meaning, however. Two other large, crescent-shaped mounds can be found west and southwest of the largest one.

The Chontal (Puntun) Maya of the Tabasco region of Mexico considered the goddess, Ixchel, to be their most important deity. 12 She was associated with the crescent moon, fertility and childbirth. The mounds they erected in Mexico to the moon goddess were often semi-circular in form. There are several other semi-circular mounds at Ortona, and many more at other ancient town sites in southern Florida. However, they are quite rare elsewhere in the United States.

There are many crescent shaped mounds in northern and central Florida. 13 The best known is at the Crystal River Archaeological Zone on the central Gulf Coast. Some seem to have developed over hundreds of years as garbage middens. Others were intentionally built in a crescent shape. There is also a crescent shaped stone mound in the acropolis of the Track Rock Terrace Complex in the Georgia Mountains. 14 It is perhaps 5% the size of the largest crescent shaped mound at Ortona.

Why was the largest temple mound at Ortona so different from most of those built by the indigenous peoples of the United States? That question can not be answered with certainty. It predates most of the ceremonial mounds built outside of Florida and Georgia. Truncated oval earthen mounds can be found in hundreds of town sites in the former Creek Homeland. However, no currently known archaeological site has the combination of two mounds, connected by causeways, and framed by a semicircular mound.

Ceremonial staffs carried by Maya sun lords

The famous murals at Bonampak, are on the walls of a temple in a Classic Period Maya city on the banks of the Usumacinta River in Chiapas State, Mexico. 15 As can be seen in the images in this article, the profile of the ceremonial staffs of nobles in several of the Bonampak murals match the profiles of the ceremonial pond and one ceremonial mound at Ortona. These profiles also match the profiles of the ceremonial scepters carried by “Mississippian” Culture nobility.

There is one significant difference between the ceremonial staffs carried by Maya Sun Lords and the ceremonial scepters carried by Southeastern nobility. Most of the ceremonial staffs had quetzal feathers attached to their heads, while the Southeastern scepters consisted of wooden handles and copper plate heads. The shorter length of the Southeastern scepters may reflect what was customary among Maya cities in Chiapas during the Late Classic or Early Post Classic Periods. The Bonampak murals are believed to date from the Middle Classic Period, about 550 AD to 800 AD.

Citations:

- How do you stem the tide of psuedo-archaeology?[↩]

- Carr, Robert S., Dicke, David & Mason, Marilyn. “Archaeological investigations at the Ortona Earthworks and Mound.” The Florida Anthropologist, Vol. 48, No. 4. December 1995.[↩]

- Thornton, Richard. Ancient Roots III: The Indigenous Peoples and Architecture of the Ocmulgee-Altamaha River Basin. Raleigh: Lulu Publishing. 2008; p.75.[↩]

- Thornton, Richard. Ancient Roots III: The Indigenous Peoples and Architecture of the Ocmulgee-Altamaha River Basin. Raleigh: Lulu Publishing. 2008; p.75.[↩]

- Carr, Robert S., Dicke, David & Mason, Marilyn. “Archaeological investigations at the Ortona Earthworks and Mound.” The Florida Anthropologist, Vol. 48, No. 4. December 1995.[↩]

- Thornton, Richard. Ancient Roots III: The Indigenous Peoples and Architecture of the Ocmulgee-Altamaha River Basin. Raleigh: Lulu Publishing. 2008; p. 16.[↩]

- Carr, Robert S., Dicke, David & Mason, Marilyn. “Archaeological investigations at the Ortona Earthworks and Mound.” The Florida Anthropologist, Vol. 48, No. 4. December 1995.[↩]

- Ringle, William F., “The 2001 Field Season of the Labná-Kiuic Archaeological Project.” FAMSI, 2005.[↩]

- Carr, Robert S., Dicke, David & Mason, Marilyn. “Archaeological investigations at the Ortona Earthworks and Mound.” The Florida Anthropologist, Vol. 48, No. 4. December 1995.[↩]

- See article on the architecture of Fort Center, Florida.[↩]

- Carr, Robert S., Dicke, David & Mason, Marilyn. “Archaeological investigations at the Ortona Earthworks and Mound.” The Florida Anthropologist, Vol. 48, No. 4. December 1995.[↩]

- Scholes, France V., and Ralph L. Roys, The Maya Chontal Indians of Acalan-Tixchel. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1968; 57, 383, 395.[↩]

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1999). Famous Florida Sites: Mount Royal and Crystal River. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. pp. 22-23.[↩]

- Thornton, Richard, The Itza Mayas in North America. Raleigh: Lulu Publishing, 2012; p. 177.[↩]

- Staines, Leticia. Coord. De la Fuente, Beatriz. Dir. La pintura mural prehispánica en México II. Área maya. Tomo I. Bonampak. Catálogo [1] Tomo II. Bonampak. Estudios [2] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, UNAM. México. 1998.[↩]