The Fort Center Mounds archaeological site was the first ancient Native American community near Lake Okeechobee to be studied thoroughly by contemporary, professional archaeologists. It was the last major archaeological project for Archaeologist, William Sears. 1 For at least two decades, many of Sears’ peers dismissed his interpretation of the site as being “off the wall” and considered him a kook. However, in recent decades work by other archeologists have confirmed his interpretation and pushed back the occupation of Fort Center even further.

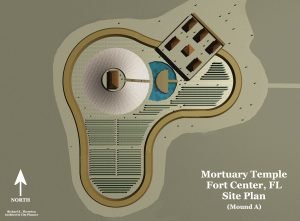

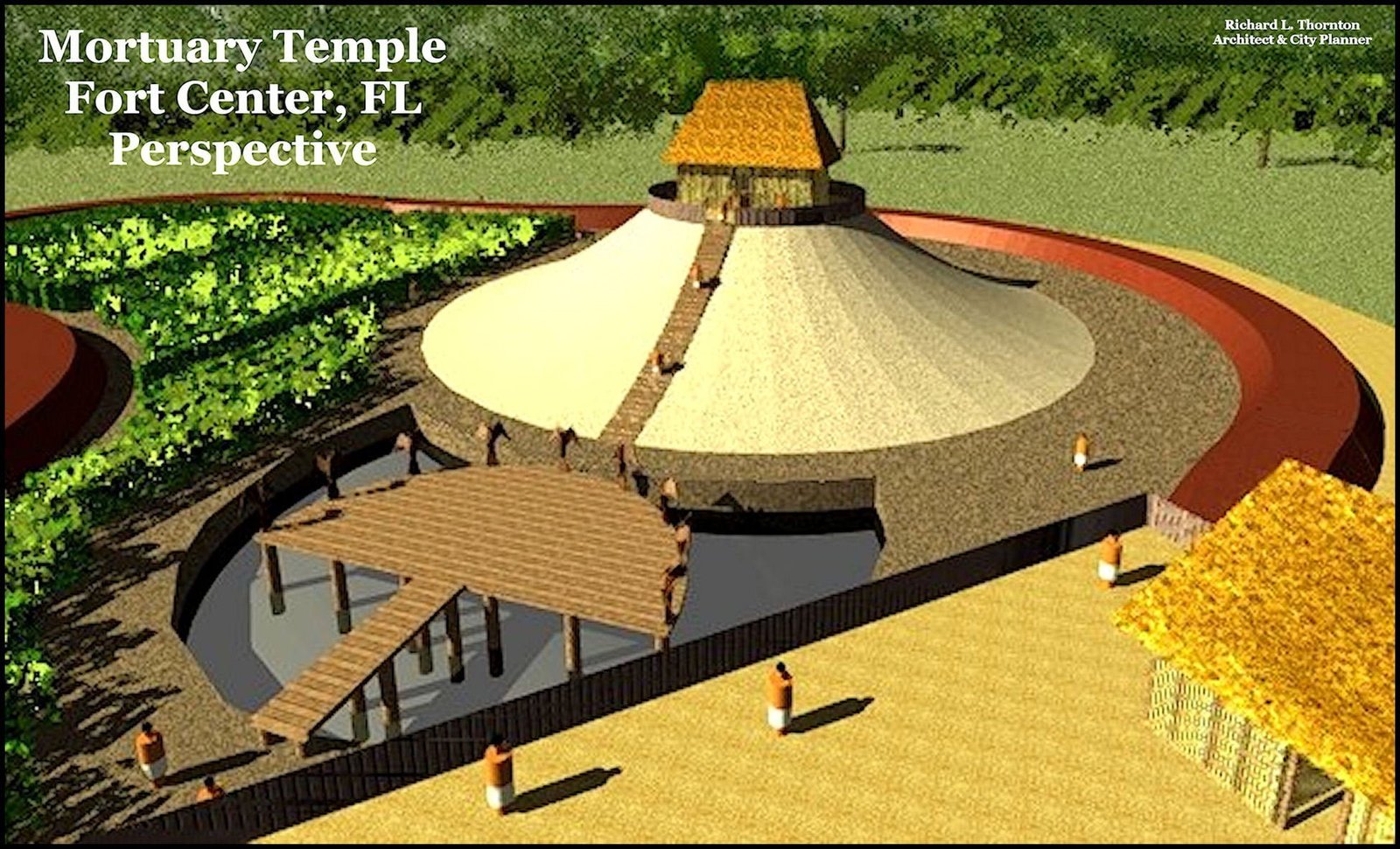

One of the most unusual examples of Native American architecture ever created was a mortuary complex at Fort Center, constructed around 200 AD. From the complexity and uniqueness of the complex, it is clear that it was “designed” and built according to the plans. The temple compound included a chevron-shaped earthen berm with rounded ends, a terrace for elite residences, a pond, a “sacred garden” for growing corn, a wooden platform for funerals, a conical mound veneered with shells imported from the coast, and a mortuary temple for cremating human remains.

The Temple’s Architecture

The Fort Center Mortuary Complex, also known as Mound A, had an overall form in its final stage, which was highly unusual for all indigenous cultures in the Western Hemisphere. It can be described roughly as a chevron shape with rounded ends. 2 The cultural significance of this shape is not known at this time. The complex seems to have originated as a house site or small burial mound. Then the chevron-shaped raised cultivation bed was created. It was surrounded by an earth berm, approximately 15-20 feet high. The purpose of the earth berm seems to have been to screen activities within the complex from public view. Over time a large conical burial mound developed at the apex of the chevron. Each stage was veneered with crushed shells transported inland from the ocean. The final stage of the earth sculpturing was the creation on one wing of the chevron, of a terrace on which elite housing was constructed.

Southeastern archaeologists tend to not think of Southeastern Native Americans as being skilled wood workers; mainly because so few wooden artifacts and art remain today. However, the tannic acid and anaerobic conditions in the peat at Fort Center preserved many carved wooden architectural details and art. Inside the Fort Center Mortuary Complex, Archaeologist William Sears found the location of the ceremonial pond. 3 Substantial evidence of both sophisticated wooden architecture and finely carved wooden objects of art, were discovered in the peat of the former pond.

A semi-circular wooden platform, edged with carved wooden herons, was constructed in the pond. 4 However, its orientation was 180 degrees opposite that of the crescent-shaped pond. Crescent shaped mounds and pools are normally associated with the Chontal Maya people of Mexico in their worship of the goddess, Ix-Chel. {See later discussion on this.] She was originally the goddess of the rainbow, but later became associated with the New Moon and human fertility. The crescent shape of Chontal Maya temple mounds was symbolic of both the rainbow and the new moon.

Obviously, there must have been some ritual reason for this visual contradiction, but it is not known. There was a raised plankway leading to the platform. Their forms were quite similar to wooden birds found at Key Marco on the Florida Gulf Coast. However, the Fort Center mortuary complex was constructed about 500 years before the final stage of the Key Marco platform village.

Apparently, the mortuary temple on top of the conical burial mounds was framed with wood timbers and used as a crematory. The actual appearance of this temple is speculative, because little remained but the humus in the post holes and the cremation hearth.

The houses on the domestic terrace were much larger and soundly constructed than typical houses at the Fort Center site. 5 All that remains of them are post holes, hearths and the detritus of daily living.

The Ceremonial Pond

A crescent-shaped pond was created at the base of the burial mound. Crescent shaped mounds and ponds are common architectural features of Lake Okeechobee towns. The crescent and semi-circle were symbols of the Maya Moon Goddess, Ixchel. She was the favorite deity of the Chontal Maya’s, who originated in the sweltering lowlands of Tabasco, Mexico. They were related to the Itza Maya of the Lake Atitlan region in the Guatemala Highlands.

There is another link between Florida and the goddess, Ixchel. The original name of the Gulf Coast between the mouth of the Mobile River and Apalachicola Bay – perhaps extending southward to the mouth of the Suwannee River – was Am Ixchel (Amichel in Spanish.) These words mean, “Place of the Goddess, Ixchel.” 6

The Chontal Maya were also known as the Puntun or Yucatec. 7 They were illiterate for many centuries, but during that time became skilled sailors and boat-builders. The Chontal eventually perfected an ocean-going sailing vessel that was similar in size and construction to famous (and feared) Viking La*’ngba*’t. They dominated the sea trade routes of Mesoamerica and the Caribbean Basin until the Spanish colonized the Caribbean.

Cultivation Areas

Much of the remaining area inside the berms was devoted to gardening. 8 The abundance of Indian corn pollen strongly suggests that maize was the primary, if not only, crop grown. Most of the maize at Fort Center was apparently cultivated in raised beds, but a few other raised beds were shielded from public view by earth berms, or associated with sophisticated architecture.

Why would corn be cultivated inside an area apparently devoted to funeral rights and cremations? Archaeologists believe that the crops harvested from this ceremonial compound had special religious significance. It currently appears that the Fort Center site had a long term monopoly on maize cultivation in southern Florida, or at least, was the only location where it was grown on a large scale. In order to maintain that monopoly, only food products processed from corn like flour, hush puppies, tortillas, tamales. hominy corn and corn beer could be traded to other communities. Sales of corn kernels would quickly result in other communities also producing corn. Here are some facts that may offer an answer:

- Hydrated lime, in large quantities was discovered at the Fort Center Mortuary Complex.

- The word “Itza” as in Itza Maya means “corn tamale.” The largest branch of the Creek Indians prior to the arrival of the Spanish, called themselves the Itsa-te, which means “Itza People. Ancestors of several Southeastern tribes, such as the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Creeks, made tamales. They were often flavored with bits of meat, beans or dried fruit.

- Balls of corn batter were fried in hickory nut oil by Muskogeans in the Southeast to increase its flavor and shelf life. This dish is now called the “hush puppy.” Travelers could carry the hush puppies in back packs for weeks in the cooler months. Often pumpkin or beans would be mixed with the corn flour to create traveling meals with more nutrition.

- The Native Americans of the lower Southeast made a mildly alcoholic corn beer. It was mentioned on several occasions by Spanish explorers.

- Many of the Southeastern mound-building cultures they shared a belief in dual souls. One manifestation of the soul has a personal identity and human qualities. It would either go to heaven or hell, depending on the virtue of the life it lived on earth. The other soul was communal and flowed from generation to generation. People of the same family shared the same communal soul in the since that scientists today describe DNA.

- Indian corn puts heavy demands on the soil for such minerals a potassium, magnesium and calcium. Early Euro-American farmers found that they could extend the fertility of cultivated fields by applying hydrated lime and potash (also known as bone meal.) Potash was originally made by cremating the skeletal remains of slaughtered livestock.

Could priests in the mortuary temple have utilized the ashes of the deceased and hydrated lime from burning shells to fertilize the “Sacred Corn Garden?”

Consumption of corn tamales, tortillas or corn beer made from corn fertilized with human remains would essentially be ritualistic cannibalism. Limited consumption of “cannibal” corn products to the elite would affirm their inherent elite status. Conversely, allowing certain individuals or communities to consume the “cannibal” corn products would ritualistically bring them into elite status. The “communal soul” of the deceased cremated remains would then flow into the body of the partaker of the sacred meal. This particular Native American temple could have been the creation of a very imaginative science fiction writer.

Citations:

- Memorial for William Hulse Sears (1909-1996) Society for American Archaeology.[

]

- Sears, William H. (1994). Fort Center: an Archaeological Site in the Lake Okeechobee Basin. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida; p. 146.[

]

- Sears, William H. (1994). Fort Center: an Archaeological Site in the Lake Okeechobee Basin. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida; p. 147.[

]

- Sears, William H. (1994). Fort Center: an Archaeological Site in the Lake Okeechobee Basin. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida; p. 147.[

]

- Sears, William H. (1994). Fort Center: an Archaeological Site in the Lake Okeechobee Basin. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida; p. 143.[

]

- Boot, Erik, “Itza Maya Dictionary.” FAMSI website.[

]

- Schele, Linda; and David Freidel (1990). A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. New York: William Morrow; p. 350.[

]

- Sears, William H. (1994). Fort Center: an Archaeological Site in the Lake Okeechobee Basin. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida.[

]