The islands and western shores of the beautiful bay which still bears their name were, at the time of the first European settlement, in the possession of the great and powerful tribe of the Narragansetts. Their dominions extended thirty or forty miles to the westward, as far as the country of the Pequots, from whom they were separated by the Pawcatuck River.

Their chief sachem was the venerable Canonicus, who governed the tribe, with the assistance and support of his nephew Miantonimo. The, celebrated Roger Williams, the founder of the Rhode Island and Providence plantations, always noted for his kindness, justice, and impartiality towards the natives, was high in favor with the old chief, and exercised an influence over him, without which his power might have been fatally turned against the English. Canonicus, he informs us, loved him as a son to the day of his death.

Mr. Williams had been obliged to leave the colony at the eastward, in consequence of his religious opinions, which did not coincide with those so strictly interwoven with the government and policy of the Puritans. He was a man of whose enterprise and wisdom the state which he first settled is justly proud, and whose liberal and magnanimous disposition stands out in striking relief when compared with the intolerant and narrow-minded prejudices of his contemporaries.

Miantonimo is described as a warrior of a tall and commanding appearance; proud and magnanimous; “subtile and cunning in his contrivements;” and of undaunted courage.

The Pequots

The Pequots and Mohegans, who formed but one tribe, and were governed during the early period of English colonization by one sachem, appear to have emigrated from the west not very long before the first landing of Europeans on these shores. They were entirely disconnected with the surrounding tribes, with whom they were engaged in continual hostilities, and were said to have reached the country they then inhabited from the north. They probably formed a portion of the Mohican or Mohegan nation on the Hudson, and arrived at the seacoast by a circuitous route, moving onward in search of better hunting grounds, or desirous of the facilities for procuring sup port offered by the productions of the sea.

In various warlike incursions they had gained a partial possession of extensive districts upon the Connecticut River, and from them the early Dutch settlers purchased the title to the lands they occupied in that region.

Murder Of Stone and Oldham Endicott’s Expedition

In the year 1634, one Captain Stone, a trader from Virginia, of whom the early narrators give rather an evil report, having put into the Connecticut River in a small vessel, was killed, together with his whole crew, by a party of Indians whom he had suffered to remain on board his vessel.

Two years later, a Mr. John Oldham was murdered at Block Island, (called Manisses in the Indian tongue,) by a body of natives. They were discovered in possession of the vessel, and endeavoring to make their escape, were most of them drowned.

The Narragansetts and Pequots both denied having participated in this last outrage, and, as respects Stone and his companions, although the Pequots afterwards acknowledged that some of their people were the guilty parties, yet they averred that it was done in retaliation for the murder of one of their own sachems by the Dutch, denying that they knew any distinction between the Dutch and English.

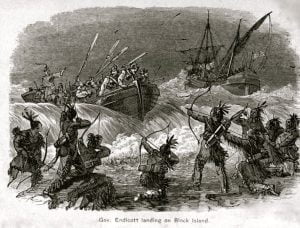

To revenge the death of Oldham, an expedition was fitted out from Massachusetts, with the avowed determination of destroying all the male inhabitants of Block Island, and of enforcing heavy tribute from the Pequots. Those engaged in the undertaking, under the command of Endicott, landed on the island, ravaged the cornfields, and burned the wigwams of the inhabitants; but the islanders succeeded in concealing themselves in the thickets, so that few were killed. Endicott thence proceeded to the Pequot country, notwithstanding the remonstrances of Gardiner, commander of the garrison at Saybrook, who told him that the consequence would only be to “raise a hornet s nest about their ears.”

Disembarking near the mouth of the Thames, the adventurers were surrounded by a large body of savages, mostly unarmed, who questioned them of their purposes with much surprise and curiosity. The English demanded the murderers, whom they alleged to be harbored there, or their heads. The Indians replied that their chief sachem, Sassacus, was absent, and sent or pretended to send parties in search of the persons demanded. Endicott, impatient of delay, and suspecting deceit, drove them off, after a slight skirmish, and proceeded to lay waste their corn-fields and wigwams, destroying their canoes and doing them incalculable mischief.

The same operations were carried on the next day, upon the opposite bank of the river, after which the party set sail for home.

The effect of procedures like these, was such as might have been expected. The hostility of the Pequots towards the whites was from this period implacable.

See Further: