For several years the tribe had been engaged in a desultory war with the Narragansetts, arising from a quarrel, in 1632, respecting the boundary of their respective do mains. Sassacus at once perceived the necessity or policy of healing this breach, and procuring the assistance of his powerful neighbors in the anticipated struggle. He therefore sent ambassadors to Canonicus, charged with proposals of treaty, and of union against the usurping English.

A grand council of the Narragansett sachems was called, and the messengers, according to Morton, “used many pernicious arguments to move them thereunto, as that the English were strangers, and began to overspread their country, and would deprive them thereof in time, if they were suffered to grow and increase;” that they need not “come to open battle with them, but fire their houses, kill their cattle, and lie in ambush for them,” all with little danger to themselves.

The Narragansetts hesitated, and would not improbably have acceded to the proposals but for the intervention and persuasion of their friend Roger Williams. His influence, combined with the hope, so dear to an Indian heart, of being revenged upon their old adversaries, finally prevailed. Miantonimo, with a number of other chiefs and warriors, proceeded to Boston; was received with much parade; and concluded a treaty of firm alliance with the English, stipulating not to make peace with the Pequots, without their assent.

Meantime, during this same year (1637), the Pequots had commenced hostilities by attacking the settlers on the Connecticut. They lay concealed about the fort at Saybrook, ready to seize any of the little garrison who should be found without the walls.

In several instances they succeeded in making captives, whom they tortured to death with their usual savage cruelty. Among the rest, a “godly young man of the name of Butterfield,” was taken, and roasted alive.

The boldness, and even temerity of the few occupants of the fort, with these horrors staring them in the face, is surprising. Gardiner, their governor, on one occasion, exasperated a body of Indians who had come forward for a species of parley, by mocking, daring, and taunting them in their own style of irony and vituperation.

The colonists appear to have been even more horror-stricken and enraged at the blasphemous language of their wild opponents, than at their implacable cruelty. When they tortured a prisoner, they would bid him call upon his God, and mock and deride him if he did so, in a manner not unlike that recorded in the case of a more illustrious sufferer.

They told Gardiner that they had “killed Englishmen, and could kill them like mosquitoes;” and that there was one among them who, “if he could kill one more English man, would be equal with God.”

Joseph Tilly, commander of a trading vessel, a man described as “brave and hardy, but passionate and willful,” going on shore, incautiously, and against the advice of Gardiner, was taken by the savages, and tortured to death in the most lingering and cruel manner, being partially dismembered, and slowly burned to death by lighted splinters thrust into his flesh. His conduct in this extremity excited the lasting admiration of his tormentors; for, like one of their own braves, he endured all with silent fortitude

The Indians were accustomed to imitate and deride the cries and tokens of pain which they usually elicited from the whites, as being unworthy of men, and tolerable only in women or children.

In April of this year (1637), an attack was made upon the village of Wethersfield, by a body of Pequots, assisted or led by other Indians of the vicinity, whose enmity had been excited by some unjust treatment on the part of the white inhabitants. Three women and six men of the colonists were killed, and cattle and other property destroyed or carried off to a considerable extent. Two young girls, daughters of one Abraham Swain, were taken and carried into captivity. Their release was afterwards obtained by some Dutch traders, who inveigled a number of Pequots on board their vessel, and threatened to throw them into the sea if the girls were not delivered up. During the time that these prisoners were in the power of the Indians, they received no injury, but were treated with uniform kindness, a circumstance which, with many others of the same nature, marks the character of the barbarians as being by no means destitute of the finer feelings of humanity.

The settlers on the Connecticut now resolved upon active operations against the Pequot tribe. Although the whole number of whites upon the river, capable of doing military service, did not exceed three hundred, a force of ninety men was raised and equipped. Captain John Ma son, a soldier by profession, and a bold, energetic man, was appointed to the command of the expedition, and the Reverend Mr. Stone, one of the first preachers at Hartford, who had accompanied his people across the wilderness, at the time of the first settlement of that town, undertook the office of chaplain a position of far greater importance and responsibility, in the eyes of our forefathers, than is accorded to it at the present day.

Letters were written to the authorities of Massachusetts, requesting assistance, inasmuch as the war was owing, in no small measure, to the ill-advised and worse conducted expedition sent forth, as we have before described, by that colony. The required aid was readily furnished, and a considerable body of men, under the command of Daniel Patrick, was sent to the Narragansett sachem, to procure his cooperation, and afterwards to join the forces of Mason.

The little army was further increased by the addition of a party of Indians, led by a chief afterwards so celebrated in the annals of the colony, as to deserve more than a casual mention upon the occasion of this, his first introduction to the reader.

Uncas, a sachem of the Mohegans, whom we have be fore mentioned as forming a portion of the Pequot tribe, had, some time previous to the events which we are now recording, rebelled against the authority of Sassacus, his superior sachem, to whom he was connected by ties of affinity and relationship.

He is described as having been a man of great strength and courage, but grasping, cunning, and treacherous, and possessed of little of that magnanimity which, though counterbalanced by faults peculiar to his race, distinguished his implacable foe, Miantonimo the Narragansett.

With his followers, a portion of whom were Mohegans, and the rest, as is supposed, Indians from the districts on the Connecticut, who had joined themselves to his fortunes, Uncas now made common cause with the whites against his own nation. Gardiner, the commandant at Saybrook, to test his fidelity, dispatched him in pursuit of a small party of hostile Indians, whose position he had ascertained. Uncas accomplished his mission, killing a portion of them, and returning with one prisoner. This captive the Indians were allowed by the English to torture to death, and they proceeded to pull him asunder, fastening one leg to a post and tying a rope to the other, of which they laid hold. Underhill, elsewhere characterized as a “bold, had man,” had, on this occasion, the humanity to shorten the torment of the victim by a pistol-shot.

The plan of campaign adopted by Mason, after much debate, was to sail for the country of the Narragansetts, and there disembarking, to come upon the enemy by land from an unexpected direction.

Canonicus and Miantonimo received the party in a friendly manner, approving the design, but proffering no assistance.

Intelligence was here received of the approach of Captain Patrick and his men from Massachusetts; but Mason determined to lose no time by waiting for their arrival, lest information of the movement should in the meantime reach the camp of the Pequots. The next day, therefore, which was the 4th of June, the vessels, in which the company had arrived from Saybrook, set sail for Pequot River, manned by a few whites and Indians, while the main body proceeded on their march across the country. About sixty Indians, led by Uncas, were of the party.

A large body of Narragansetts and Nehantics attended them on their march, at one time to the number, as was supposed, of nearly five hundred. In Indian style, they made great demonstration of valor and determination; but as they approached the head-quarters of the terrible tribe that had held them so long in awe, their hearts began to fail. Many slunk away, and of those who still hung in the rear, none but Uncas and Wequash, a Nehantic sachem, were ready to share in the danger of the first attack.

The Pequot camp was upon the summit of a high rounded hill, still known as Pequot hill, in the present town of Groton, and was considered by the Indians as impregnable. The people of Sassacus had seen the English vessels pass by, and supposed that danger was for the present averted. After a great feast and dance of exultation at their safety and success, the camp was sunk in sleep and silence. Mason and his men, who had encamped among some rocks near the head of Mystic River, approached the Pequot fortification a little before day, on the 5th of June.

The alarm was first given by the barking of a dog, followed by a cry from some one within, of “Owanux, Owanux” the Indian term for Englishmen upon which the besiegers rushed forward to the attack.

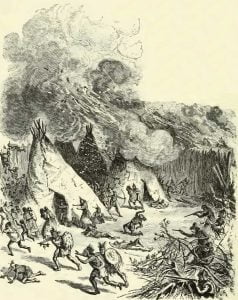

Destruction of the Pequot Fort

The fort was, as usual, enclosed with thick palisades, a narrow entrance being left, which was barred by a pile of brushwood. Breaking through this, Mason and his companions fell upon the startled Pequots, and maintained for some time an uncertain hand to hand conflict, until, all order being lost, he came to the savage determination to fire the wigwams. This was done, and the dry materials of which these rude dwellings were composed blazed with fearful rapidity.

The warriors fought desperately, but their bowstrings snapped from the heat, and the Narragansetts, now coming up, killed all who attempted to escape. The scene within was horrible beyond description. The whole number destroyed (mostly by the flames) was supposed to be over four hundred, no small portion of which consisted of women and children.

The spirit of the times cannot be better portrayed than by citing the description of this tragedy given by Morton: “At this time it was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fire, and the streams of blood quenching the same; and horrible was the stink and scent thereof; but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave the praise thereof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them, thus to enclose their enemies in their hands, and give them so speedy a victory over so proud, insulting, and blasphemous an enemy.” Dr. Increase Mather, in much the same vein, says: “This day we brought six hundred Indian souls to hell.”

In looking back upon this massacre, although much allowance must be made for the rudeness of the age, and the circumstances of terror and anxiety which surrounded the early settlers, yet we must confess that here, as on other occasions, they exhibited the utmost unscrupulousness as to the means by which a desired end should be accomplished.

The loss of the attacking party in this engagement was trifling in the extreme, only two of their number being killed, and about twenty wounded. Captain Patrick with his soldiers from Massachusetts, did not reach the scene of action in time to take part in it Underhill, however, with twenty men, was of the party.

The Tribe Dispersed And Subdued

The result of this conflict was fatal to the Pequots as a nation. After a few unavailing attempts to revenge their wrongs, they burned their remaining camp, and commenced their flight to the haunts of their forefathers at the westward.

They were closely pursued by the whites and their Indian allies, and hunted and destroyed like wild beasts. The last important engagement was in a swamp at Fair-field, where they were completely overcome. Most of the warriors were slain, fighting bravely to the last, and the women and children were distributed as servants among the colonists or shipped as slaves to the West Indies; “We send the male children,” says Winthrop, “to Burmuda, by Mr. William Pierce, and the women and maid children are dispersed about in the towns.” It is satisfactory to reflect that these wild domestics proved rather a source of annoyance than service to their enslavers.

Sassacus, Mononotto, and a few other Pequot warriors, succeeded in effecting their escape to the Mohawks, who, however, put the sachem and most of his companions to death, either to oblige the English or the Narragansetts.

The members of the tribe who still remained in Connecticut were finally brought into complete subjection. Many of them joined the forces of the now powerful Uncas; others were distributed between the Narragansetts and Mohegans; and no small number were taken and deliberately massacred.

The colonial authorities demanded that all Pequots who had been in any way concerned in shedding English blood should be slain, and Uncas had no small difficulty in retaining his useful allies, and at the same time satisfying the powerful strangers whose patronage and protection he so assiduously courted.