Territorial Limits – The World’s Wonderland – Rivers, Mountains, and Valleys – Phenomenal Features – Lava- fields – Mineral Springs – Climate – Scores of Limpid Lakes – Origin of the Name “Idaho” – In-difference of Early Immigrants – Natural Productions – Game – Food Supply – Furbearing Animals – First Mormon Settlement – County Divisions of Idaho as Part of Washington

The territory of Idaho was set off by congress March 3, 1863. It was erected out of the eastern portion of Washington with portions of Dakotah and Nebraska, and contained 326,373 square miles, lying between the 104th and 117th meridians of longitude, and the 42d and 49th parallels of latitude. It embraced the country east of the summits of the Rocky Mountains to within fifty miles of the great bend of the Missouri below the mouth of the Yellowstone, including the Milk River, White Earth, Big Horn, Powder River, and a portion of the Platte region on the North Fork and Sweetwater. Taken all together, it is the most grand, wonderful, romantic, and mysterious part of the domain enclosed within the federal union.

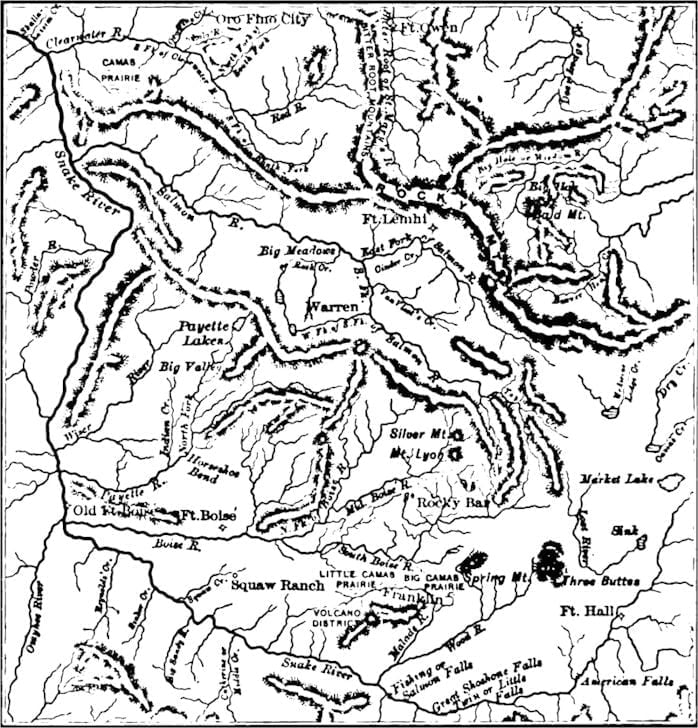

Within its boundaries fell the Black Hills, Fort Laramie, Long’s Peak, the South Pass, Green River, Fort Hall, Fort Boise, with all that wearisome stretch of road along Snake River made by the annual trains of Pacific-bound immigrants since 1843, and earlier. Beyond these well-known stations and landmarks no information had been furnished to the public concerning that vast wilderness of mountains interspersed with apparently sterile sand deserts, and remarkable, so far as understood, only for the strangeness of its rugged scenery, which no one seemed curious to explore.

The Snake River, 1 the principal feature known to travelers, is a sullen stream, generally impracticable, and here and there wild and swift, navigable only for short distances, above the mouth of the Clearwater, broken by rapids and falls, or coursing dark and dangerous between high walls of rock. Four times between Fort Hall and the mouth of the Bruneau, a distance of 150 miles, the steady flow of water is broken by falls. The first plunge at American Falls, 2 twenty-five miles from Fort Hall, is over a precipice 60 feet or more in height, after which it flows between walls of trap-rock for a distance of 70 miles, when it enters a deeper canon several miles in length and from 800 to 1,000 feet in width, emerging from which it divides and passes around a lofty pinnacle of rock standing in the bed of the stream, the main portion of the river rushing over a ledge and falling 180 feet without a break, while the smaller stream descends by successive plunges in a series of rapids for some distance before it takes its final leap to the pool below. These are called the Twin Falls, and sometimes the Little Falls to distinguish them from the Great Shoshone Falls, four miles below, where the entire volume of water plunges down 210 feet after a preliminary descent of 30 feet by rapids. Forty miles west, at the Salmon or Fishing falls, the river makes its last great downward jump of forty feet, after which it flows, With frequent rapids and canons, onward to the Columbia, 3 in some places bright, pure, and sparkling with imprisoned sunshine, in others noiseless, cold, and dark, eddying like a brown serpent among fringes of willows, or hiding itself in shadowy ravines untrodden by the footsteps of the all dominating white man.

This 500 feet of descent by cataracts is made on the lower levels of the great basin, where the altitude above the sea is from 2,130 feet, at the mouth of the Owyhee, to 4,240 at the American Falls. The descent of 2,110 feet in a distance of 250 miles is sufficient explanation of the unnavigable character of the Serpent River. Other altitudes furnish the key to the characteristics of the Snake Basin. The eastern gate-way to this region, the South Pass, is nearly 7,500 feet high, and the mountain peaks in the Rocky range from 10,000 to 13,570 feet, the height of Fremont Peak. The pass to the north through the Blackfoot country is 6,000 feet above the sea, which is the general level of that region, 4 while various peaks in the Bitter Root range rise to elevations between 7,000 and 10,000 feet. Florence mines, where the discoverers were rash enough to winter, has an altitude of 8,000 feet, while Fort Boise is 6,000 feet lower, being in the lowest part of the valley of Snake River. Yet within a day’s travel on horseback are rugged mountains where the snow lies until late in the spring, topped by others where it never melts, as the miners soon ascertained by actual experience. The largest body of level land furnished with grass instead of artemesia is Big Camas prairie, on the head waters of Malade or Wood River, containing about 200 square miles, but at an altitude of 4,700 feet, which seemed to render it unfit for any agricultural purposes, although it was the summer paradise of the United States cavalry for a time, and of horse and cattle owners.

There are valleys on the Payette, Clearwater, lower Snake, Boise, Weiser, Blackfoot, Malade, and Bear Rivers, besides several smaller ones. They range in size from twenty to a hundred miles in length, and from one to twenty miles in width, and with other patches of fertile land aggregate ten millions of acres in that part of the new territory whose altered boundaries now constitute Idaho, all of which became known to be well adapted to farming and fruit-raising, although few persons were found at first to risk the experiment of sowing and planting in a country which was esteemed as the peculiar home of the mineralogist and miner.

In a country like this men looked for unusual things, for strange phenomena, and they found them. A volcano was discovered about the head waters of the Boise, which on many occasions sent up smoke and columns of molten lava 5 in 1866, and in August 1881 another outburst of lava was witnessed in the mountains east of Camas prairie, while at the same time an earthquake shock was felt. In 1864 the Salmon River suddenly rose and fell several feet, rising a second time higher than before, being warm and muddy 6 .

Notwithstanding the evidences of volcanic eruptions, and the great extent of lava overflow along Snake River, the country between Reynolds Creek in Owyhee and Bruneau River was one vast bed of organic remains, where the bones of extinct species of animals were found 7 , and also parts of the human skeleton of a size which seemed to point to a prehistoric race of men as well. This portion of the ancient lakebed seemed to have received, from its lower position, the richest deposit of fossils, although they were found in higher localities. All the streams emptying into Snake River at some distance below the Shoshone or Great falls sink before reaching it, and flow beneath the lava, shooting out of the sides of the canon with beautiful effect, and forming a variety of cascades. 8 “Salmon River,” said one of the mining pioneers, “almost cuts the earth in two, the banks being 4,000 feet perpendicular for miles, and backed by rugged mountains that show evidences of having been rent by the most violent convulsions 9 Godin 10 or Lost River is a considerable stream rising among the Wood River Mountains and disappearing near Three Buttes – hence the name – though coming to the surface afterward. Journeying to Fort Hall by the way of Big Camas prairie, 11 after reaching the lava-field you pass along the base of mountains whose tops glisten with perpetual snow. Stretching southward is a sea of cinder, wavy, scaly, sometimes cracked and abysmal. Bruneau River and the Owyhee drain the southern and western side. Curious mineral springs have been discovered in various parts, the most famous of which are the soda springs in the Bear River region, of which thousands have tasted on their journey across the continent. Around the springs are circular embankments of pure snow-white soda several feet in height and twenty to thirty feet in diameter. You may count fifty mineral springs within a square mile in Bear River Valley, some of pure soda, some mingled with sulphur, and others impregnated with iron; some warm, some cold, some placid, others bubbling and noisy as steam, the waters of which could be analyzed, but could not be reproduced. 12

It was the common judgment of the first explorers that there was more of strange and awful in the scenery and topography of Idaho than of the pleasing and attractive. A more intimate acquaintance with the loss conspicuous features of the country revealed many beauties. The climate of the valleys was found to be far milder than from their elevation could have been expected. Picturesque lakes were discovered nestled among the mountains, or furnishing in some instances navigable waters. 13 Fish and game abounded. Fine forests of pine and fir covered the mountain slopes except in the lava region; and nature, even in this phenomenal part of her domain, had not forgotten to prepare the earth for the occupation of man, nor neglected to give him a wondrously warm and fertile soil to compensate for the labor of subduing the savagery of her apparently waste places. 14

What has been said of the Snake Basin and Salmon and Clearwater regions leaves untouched the wonderland lying at the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains on the upper waters of the Yellowstone River, and all the imposing scenery of the upper Missouri and the Clarke branch of the Columbia – the magnificent mountains, and grand forests, the rich if elevated valleys, and the romantic solitudes of that more northern division of Idaho as first organized under a temporary government, which was soon after cut off and erected into a separate territory. Once it had all been Oregon west of the Rocky Mountains; then it was all Washington north and cast of Snake River; now all east of that stream bore another name, a Shoshone word, signifying “gem of the mountains,” or more strictly, “diadem of the mountains,” referring to the lustrous rim shown by the snowy peaks as the sun rises behind and over them. 15

The natural food resources of Idaho were not those of a desert country. Sturgeon of immense size were found in the Snake River as high up as Old’s ferry. Salmon crowded that stream and its tributaries at certain seasons. The small rivers abounded in salmon-trout. The lakes were filled with fish of a delightful flavor. One species, for which no name has yet been found, belonged especially to the Payette lakes, of a bright vermilion color, except the fins, which are dark green. They probably belonged to the salmon family, as their habit in respect of ascending to the head waters of the river to spawn and die are the same as the Columbia salmon. 16

The mountains, plains, and valleys abounded with deer, bear, antelope, elk, and mountain sheep. 17 The buffalo which once grazed on the Snake River plains had long been driven east of the Rocky Mountains. Partridge, quail, grouse, swan, and wild duck were plentiful on the plains and about the lakes. Fur bearing animals, once hunted out of the mountains and streams by the fur companies, had again become numerous. The industrious beaver cut down the young Cottonwood trees as fast as they grew in the Bruneau Valley, depriving future settlers of timber, but preserving for them the richest soil. The wolf, red and silver-gray fox, marten, and muskrat inhabited the mountains and streams.

Grapes, cherries, blackberries, gooseberries, whortleberries, strawberries, and salmon-berries, of the wild varieties, had their special localities. Blackberries and grapes were abundant, but, owing to the dry climate, not of the size of these wild fruits in the middle states. Camas root, in the commissary department of the natives, occupied a place similar to bread, or between wheat and potatoes, in the diet of agricultural nations. It resembled an onion, being bulbous, while in taste it was a little like a yam. The qullah, another root, smaller and of a disagreeable flavor, was eaten by the Indians when cooked. In taste it resembled tobacco, and was poisonous eaten raw. The botany of the country did not differ greatly from some parts of Oregon, either in the floral or the arboreous productions. The most useful kinds of trees were the yellow pine, sugar pine, silver pine, white fir, yellow fir, red fir, white cedar, hemlock, yew, white oak, live oak, cottonwood, poplar, mountain mahogany, and madrono. The great variety of shrubby growths are about the same as in southwestern Oregon.

Two years previous to the passage of the organic act of Idaho there had been but two or three settlements made within its limits, if the missions of the Jesuits are excepted. It was not regarded with favor by any class of men, not even the most earth-hungry. Over its arid plains and among its fantastic upheavals of volcanic rocks roamed savage tribes. Of the climate little was known, and that little was unfavorable, from the circumstance that the fur companies, who spent the winters in certain localities in the mountains, regarded all others as inhospitable, and the immigrant judged of it by the heat and drought of midsummer.

Idaho 1863

But early in 1854 a small colony of Mormon men was sent to found a settlement on Salmon River among the buffalo-hunting Nez Percé, who erected a fort, which they named Lemhi. In the following year they were re-enforced by others, with their families, horses, cattle, seeds, and farming implements; and in 1857 Brigham Young visited this colony, attended by a numerous retinue. He found the people prosperous, their crops abundant, the river abounding in fish, and the evidences present of mineral wealth. When he returned to Salt Lake the pioneers returned with him to fetch their wives and children. The Nez Percé, however, became jealous of these settlers, knowing that the government was opposed to the Mormon occupation of Utah, and fearing lest they should be driven out to overrun the Flathead country if they were permitted to retain a footing there. 18 The colony finally returned to Salt Lake, driven out, it was said, by the Indians, with a loss of three men killed, and all their crops destroyed. 19 The other settlements were a few farms of French Canadians in the Coeur d’Alene country, the Jesuit missions, and Fort Owen, the latter east of the Bitter Root Mountains, in the valley of the St Mary branch of Bitter Root River.

The county of Shoshone was set off from Walla Walla County by the legislature of Washington as early as January 29, 1858, comprising all the country north of Snake River lying east of the Columbia and west of the Rocky Mountains, with the county seat “on the land claim of Angus McDonald.” 20 This was subdivided by legislative acts in 1860-1 and 1861-2, as the requirements of the shifting mining population, of which I have given some account in the History of Washington, demanded.

This mining population, as I have there stated, first overran the Clearwater region, discovering and opening between the autumn of 1800 and the spring of 1863 the placers of Oro Fino Creek, North Fork and South Fork of the Clearwater, Salmon River and its tributaries, and finally the Boise basin; at which point, being nearly coincident with the date of the territorial act, I will take up the separate history of Idaho 21.

History Of Washington, Idaho, And Montana, Volume 31, 1845-1889, Hubert H. Bancroft, 1890.

Citations:

- The name of this stream was taken from the natives inhabiting its banks, and has been variously called Snake, Shoshone, and Les Serpents. Lewis and Clarke named it after the former – Lewis River. See Native Races of Pacific States, and Hist. Northwest Coast, passim, this series[

]

- So named from the loss of a party of Americans who attempted to navigate the river in canoes. Palmer’s Jour. 44[

]

- Ribllett’s Snake River Region, MS., 2-4; Starr’s Idaho, MS., 4; Idaho Scraps, 27, 35; Boise Statesman, July 4, 1868; Portland West Shore, July 1877[

]

- The mean altitude of Montana is given as 3,900 feet in Gannett’s List of Elevations, 161[

]

- Buffalo Hump, an isolated butte between Clearwater and Salmon rivers, is the mountain here referred to. The lava overflow was renewed in September, when “great streams of lava” were “running down the mountain, the molten substance burning everything in its path. The flames shoot high in the air, giving at a long distance the appearance of a grand conflagration. ” A rumbling noise accompanied the overflow. Wood River Miners Sept. 21, 1881; Idaho World, June 30, I866; Silver City Avalanche, Jan. 29, 1881[

]

- John Kennan of Florence witnessed this event. Boise News, Aug. 13, 1864[

]

- Early Events, MS., 9. H. B. Maize found a tusk 9 inches in diameter at the base and 6 feet long embedded in the soil on Rabbit Creek, 10 miles from Snake River, and a variety of other bones. Boise Statesman, Oct. 1, 1870. This bed appears to be similar to one which exists in a sand deposit in south-eastern Oregon, and described by O. C. Applegate in Portland West Shore, July 1877[

]

- Riblett’s Snake River Region, MS., 2-4. In this descriptive manuscript, by Frank Riblett, surveyor of Cassia County, some strong hints are thrown out. Riblett says: ‘The lava presents phenomena like breathing holes, where strong currents of air find continual vent. Chasms going seemingly to immense depths; corrals – called devil’s corrals, being enclosures of lava walls – extinct craters; the City of Rocks, a pile of basalt, which resembles a magnificent city in ruins … Massacre Gate is a tremendous basaltic barrier running from the bluffs to Snake River, and cleft only wide enough to permit the passage of a wagon, so named from a massacre by Indians at this place; also variously styled Gate of Death and Devil’s Gate[

]

- Hofen’s Hist. Idaho County, MS., 7[

]

- Named after a trapper in the service of the American Fur Company. Godin is mentioned in Victor’s River of the West 129-30. He was killed at this stream by the Blackfoot Indians. Townsend’s Nar. 114[

]

- Called Big Camas to distinguish it from the North Camas prairie situated between the Clearwater and Salmon Rivers, and other tracts of similar lands. There is also a Little Camas prairie south of Big Camas prairie[

]

- Idaho Scraps, 60-1; Salt Lake Tribune, Jan. 1, 1878; Codman’s Round Trip, 254-9; Strahorn’s To the Rockies, 120. At some springs 4 miles from Millersburg a bathing-house has been built. Hofen’s Hist. Idaho Co. MS., 6. In 1865-6 James H. Hutton erected baths at the warm springs near Warren. Statement by Edwin Farnham, in Schultzt’s Early Anecdotes, MS., 6; Owyhee Avalanche, April 17, 1870. On Bruneau River, at the Robeson farm, are several hot springs, and one of cold sulphur water. Near Atlanta, on the middle fork of Boise, were discovered warm springs fitted up for bathing by F. V. Carothers in 1877. Silver City Avalanche, May 5, 1877. Near Bonanza, on Yankee Fork of Salmon River, were found sulphur springs of peculiar qualities. Bonanza City Yankee Fork Herald, March 20, 1880. In short, the whole basin between Salmon River and Salt Lake was found to be dotted with springs of high temperature and curative medicinal qualities[

]

- Lakes Coeur d’Alene and Pend d’Oreille are of the navigable class, the former 35 miles long, the latter 30 miles. Steamers ply on the Coeur d’Alene. Cocolala is a small lake. Kaniskee is a limpid body of water 20 miles long by 10 wide. Hindoo lakes are a group of small bodies of alkaline water of medicinal qualities. And there are a score or two more well worthy of mention[

]

- For general description of Idaho, see H. Ex. Doc, i. pt 4, 133-8, 4lst cong. 3d sess; Rusling’s Across the Continent, 206-50; Edmonds, in Portland Oregonian, April 19, 1864; Meagher, in Harper’s Mag., xxxv. 568-84; McGabe’s Our Country, 1092; Browne’s Resources, 512-16; Ebey’s Journal, MS., i. 253; Campbell’s Western Guide, 60-4; Hayden’s Geological Rept, in H. Ex, Doc., 326, XV, 42d cong. 2d sess; Idaho Scraps, 27, 235; Lewiston Signal, Aug. 23, 1873; Elliott’s Hist, Idaho, 86-108; Strahorn’s Idaho, 7-84; Strahorn’s Illustrated New West; and many more miscellaneous sketches of travelers and military men, as well as surveyors of railroad routes and land com-missioners. While a volume of description might be written, I have sought only by touches here and there to outline the general characteristics of the country[

]

- Pac. Monthly, xi, June 1864, 675. There seems to be no question of the meaning of the word, which is vouched for by numerous authorities. C. H. Miller, in Elliot’s Hist, Idaho, 80, affects to give the distinction of naming Idaho to William Craig. I do not see, however, that Craig had anything to do with it, even thou he had mentioned to others, as he did to Miller, the signification of the word. It had been in use as the name of a steamboat on the Columbia above The Dalles since the spring of 1860, but Miller says he never heard the word until the spring of 1861, when traveling to Oro Fino with Craig. He also says that the Indian word was E-dah’-hoe, and that he gave it to the world in its present orthography in a newspaper article in the autumn of 1861. It had been painted “Idaho” on the O. S. N. steamer for 18 months, where it was visible to thousands travelling up the Columbia. The inference which Miller would establish is that he, with Craig s assistance, suggested the name of the territory of Idaho. See Idaho Avalanche, in Walla Walla Statesman, Dec. 11, 1880. Another even more imaginative writer is William O. Stoddard, in an article in the N. Y. Tribune, who states that the word ‘Idaho’ was coined by an eccentric friend of his, George M, Willing, ‘first delegate to congress.’ As no such man was ever a delegate, and as the territory must have been created and named before it could have a delegate, this fiction ceases to be interesting. See Boise Statesman, Jan. 8, 1876; Idaho World in Ibid; S. F. Chronicle, May 1, 1876. There is a pretty legend connected with the word ‘Idaho.’ It is to the effect that E. D. Pierce met with an Indian woman of the northern Shoshones who told him of a bright object which fell from the skies and lodged in the side of a mountain, but which, although its light could be seen, could never be found. Pierce, it is said, undertook to find this Koohinoor, and while looking for it discovered the Nez Percé mines. Owyhee Avalanche, March 10, 1876. Another reasonable story is that when W. H. Wallace was canvassing for his election as delegate from Washington in 1861 with Lander and Garfielde, it was agreed at Oro Fino that whichever of the candidates should be elected, should favor a division of the territory. The question of a name coming up, George B. Walker suggested Idaho, which suggestion was approved by the caucus. From the fact that the first bill presented called the proposed new territory Idaho, it is probable that the petitioners adhered to the agreement. There appears to have been three names before the committees, Shoshone, Montana, and Idaho. See Cong, Globe, 1862-3, pt i., p. 166; and that Senator Wilson of Massachusetts, when the bill creating the territory of ‘Montana’ was about to pass, insisted on a change of name to Idaho, on the ground that Montana was no name at all, while Idaho had a meaning. In this amendment he was supported by Harding of Oregon. Wilson’s amendment was agreed to[

]

- Strahorn’s To the Rockies, 124; Olympia Wash. Democrat, Dec. 10, 1864; Idaho World, Aug. 15, 1874; Salt Lake Tribune, Jan. 1, 1878[

]

- A new species of carnivorous animal, called the ‘man-eater,’ was killed near Silver City in 1870. Its weight was about 100 lbs, legs short, tail bushy and 10 inches long, ears short, and feet large – a nondescript. Silver City Idaho Avalanche, March 12, 1870[

]

- Stevens’ Nar., in Pac. R. R. Rept, xii. 252; letter of R. H. Lansdale, in Ind. Aff. Rept, 1867, 380; Roes Browne, in H Ex. Doc., 39, p. 30, 35th cong. 1st sess; Olympia Pioneer and Dem., Aug. 8, 1856; Or. Statesman, Sept. 15, 1857; Rept Com. Ind. Aff., 1857, 324-80[

]

- This was in 1858, if I understand Owen’s account, in Ind. Aff. Rept, 1859, 424. Shoup, in Idaho Ter MS. 5, refers to this settlement. The Mormons erected their houses inside of a. palisade, and could have been reinforced from Salt Lake. It is probable that Brigham called them in to strengthen his hands against the government[

]

- McDonald was the H. B. Co.’s agent at Colville. The county commissioners, excepting John Owen, who was U. S. Indian agent, were of foreign birth; namely, Robert Douglas and William McCreany. Patrick McKinzie was appointed sheriff, and Lafayette Alexander county auditor. Wash Law 1858,51. Another act, repealing this, and without altering the boundaries, giving it the name of Spokane, and making new appointments, was passed Jan. 17, 1860. In this act James Hayes, Jacques Dumas, and Leaman were made commissioners, John Winn sheriff, R. K. Rogers treasurer, Robert Douglas auditor, J. R. Bates justice of the peace, and F. Wolf coroner. The county seat was removed to the land claim of Bates. The following year all that part of Spokane County lying east of the 115th line of longitude, and west of the summit of the Rocky Mountains, was stricken off and became Missoula County, with the county seat ‘at or near the trading post of Worden & Co., Hellgate Road.’ The commissioners of the new county were C. P. Higgins, Thomas Harris, and F. L. Worden; justice of the peace, Henri M. Chase; sheriff, Tipton. A new county of Shoshone was created of the territory lying south of a line drawn east from the mouth of the Clearwater to the 115th meridian, thence south to the 46th parallel, and east again to the Rocky Mts, pursuing their summits to the 42d parallel, whence it turned west to the boundary line of Oregon, following that and Snake River to the place of beginning. No officers were appointed for Shoshone Co., but it was attached to Walla Walla County for judicial purposes until organized by the election of proper county officers. The legislature of 1861-2 abridged the boundaries of Shoshone Co., by making it begin at the mouth of the south branch of the Clearwater, following the line of the river south to the Lolo fork of the same, then east with the Lolo fork to the summit of the Bitter Root Mountains, thence north to the main divide between the north branch of the Clearwater and the Palouse River, thence in a westerly direction with the divide to a point from which, running due south, it would strike the mouth of south fork. This change made Shoshone County as small as it was before great, and gave room for organizing two other counties: first, Nez Perce, comprising the territory embraced within the following limits: beginning at the mouth of the main Clearwater, following it to the south fork, and along Lolo fork to the top of the Bitter Root range, thence south to the main divide between south fork and Salmon River, following it westerly to Snake River, and thence down Snake River to the place of commencement. The second division included all that was left of Shoshone south of Nez Percé, and was named Idaho County, the name afterward chosen for the territory in which it was embraced. The officers appointed for Idaho County were Robert Gray, Robert Burns, and Sanbourn commissioners, Jefferson Standifer sheriff, and Parker justice of the peace. For Nez Percé County A. Creaey and Whitfield Kirtley were made commissioners, J. M. Van Valsah auditor, and Sandford Owens sheriff, until the next general election. At the session of 1862-3 the county of Boise was organized, embracing that portion of Idaho County bounded north by a line commencing at the mouth of the Payette River, and extending up that stream to the middle branch, and up it to its source, thence east to the summit of the Bitter Root range, which it followed to the Rocky Mts. All that lay south of that cast and west line was Boise County as it existed when the territory was organized. The county seat was located at the mouth of Elk Creek on Moore Creek. The commissioners were John C. Smith, Frank Moore, W. B. Noble; D. Gilbert probate judge, David Mulford sheriff, David Alderson treasurer, A. D. Saunders auditor, J. M. Murphy, Swan, and Baird justices of the peace, James Warren coroner. Wash. Laws 1862-3, 3-4[

]

- There arc few publications concerning Idaho, which has not yet become, as it some time will, a prominent field for tourists and writers. Among those who have written with a view to making known the geography, topography, and resources of the country, Robert K. Strahorn holds the principal place, his To the Rockies, Idaho, the Gem of the Mountains and miscellaneous writings, furnishing the source from which other writers draw their facts without the trouble of personal observation. Elliott’s History of Idaho is a compilation of articles on the early discoveries, political events, growth of towns, scenery, resources, and biography of pioneers. It is useful as a source from which to draw information on individual topics, but has no consecutive historical narrative. Idaho; A Descriptive Tour and Review of Its Resources, by G. Aubrey Angelo, published in 1865 at San Francisco, is a fair report in 60 pages upon the scenery along the road from Portland, and description of mining camps. Mullan’s Military Road Report contains a history of the expedition, its itinerary, description of passes, and reports of engineers and explorers. A Thousand Miles through the Rocky Mountains, by A. K. McClure, Phila, 1859, is a republication of letters to the N. Y. Tribune and Franklin Repository during a 9 months’ tour in 1867, containing observations on the country, and the advantages of the Northern over the Central Pacific railroad. Idaho, a pamphlet by James L. Onderdonk, controller, published in 1S33, contains a sketch of early Idaho history, and descriptions of the resources of the country, not differing essentially from what has been given by others. It is intended to stimulate immigration. Idaho and Montana, by J. L. Campbell, Chicago, 1865, is a guidebook describing routes, with some descriptive and narrative matter, in pamphlet form[

]