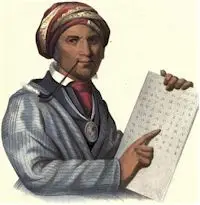

Most every school child knows the true story of the great Cherokee, Sequoya. He was born in 1770 or 1776 at a Cherokee town named Tuskegee in eastern Tennessee. 1 Sequoya stated that when an Iroquoian Peace Delegation visited at Chota in 1770, he was living with his mother as a small boy and remembered the events. While in Washington in 1828, he told Samuel Knapp he was about 65. 2 His birth name was either George Guess or George Gist. His father was a white man named George/Nathaniel Gist/Guess or a half blood Cherokee of the same name. 3 His mother was the beautiful full-blood/half-blood Wurtah, Wutah or Wuta-he, the daughter of a great Cherokee Chief in the Paint Clan and therefore, of Cherokee royalty. Some official stories of Sequoya, such as in Wikipedia, make him an only child. Other histories give him siblings and provide their names.

Most histories state that at age 10 he and his mother moved alone to a spacious log cabin and trading post in the Cherokee town of Chota on the Little Tennessee River. As a youth, he herded cattle and raised vegetables in a garden, while his mother ran a trading post. 4

Inventor of the Cherokee Alphabet

When he became a man, he took on his mother’s name of Sequoya and moved to Wills Town on the Tennessee River in Alabama, which was far removed from any white settlements. Alternatively, his mother and he moved their trading post to Wills Town. 5 Alternatively, he moved to Wills Town after his mother died, where he alone ran a tavern. Alternatively, he moved to Arkansas in the 1780s, because white men were moving into Tennessee and taking over the best hunting land. 6

On becoming a man, George Guess/Gist also became a skilled silversmith in addition to running a tavern. He had become lame at an early age, which prohibited him from herding cattle, farming, hunting or going to war. 7 Much of his sales of silverware were to the many whites living near Wills Town, which was far removed from any white settlements. He came to hate his white neighbors. This caused him to change his name to his mother’s name of Sequoya, to express his pride in being Indian. 8

Alternatively, while living in Pine Log, GA he became even closer friends with his fellow Chickamauga Warriors and neighbors, the Ridge, the Vann and the Hicks families. The Vann’s quickly became wealthy and therefore patrons of Sequoya’s talent at making silverware. The income from silverware and jewelry gave him the leisure time to pursue intellectual interests, such as creating a Cherokee writing system.

In Wills Town Sequoya became a skilled hunter and feared warrior, which enabled him to marry in 1815, the beautiful, full-blooded Cherokee Sally Benge, the sister or daughter of a great, red-haired, Cherokee chief named Robert Benge. 9 Robert Benge, had so much European DNA in him that he passed for a full-blooded Scotsman. 10 Sally had red/brown/black hair and a bronze/fair complexion.

George Guess had no formal education in the European sense, but he dreamed of his people being able to communicate with paper in the same way as white men. He then independently developed a writing system for his people. 11 He was frustrated for several years because he couldn’t create a system like the white man had. His wife, being the pure-blood Cherokee daughter of a famous 1/16th Cherokee chief, didn’t understand what he was doing. She accused him of witchcraft and burned all of the bark shingles that he used for writing pads. 12 He left her. Then to show his love and admiration for white people, the 43 or 53 years old, lame, alcoholic, tavern owner and silversmith to wealthy whites, walked all the way from Arkansas to Wills Town to enlist in the United States Army of Gen. Andrew Jackson. Red Stick Creek Indians had gone to war in protest to the illegal encroachment of white settlers on Creek owned land. 13

After helping defeat the fellow Native Americans who lived on the other side of Lookout Mountain from Wills Town, he became enlightened. He walked back to Arkansas, married another Cherokee woman, who was the daughter/niece/sister of Chief Jolly. 14 Here he spent his last days except when he was living in Mexico, Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia.

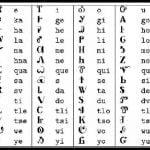

Sequoya did not succeed until he gave up trying to represent entire words and developed a symbol for each syllable in the language. According to Elias Boudinot (editor of the Cherokee Phoenix Newspaper) after approximately a month, he had a system of 86 characters, some of which were Latin letters he obtained from a spelling book. 15 In other words, Boudinot told the Cherokees and other readers of his newspaper that the writing system that Sequoya created in one month was the same as the one used by the Cherokee Phoenix and in the Holy Bible published by the Rev. Samuel Worcester.

The lame and by now, elderly Sequoya, again walked from Arkansas to northwest Georgia to present his syllabary to the Cherokee National Council. 16 It was immediately accepted. Soon all Cherokees were learning his syllabary. In a matter of a few years, the Cherokees were more literate than their white neighbors. Sequoya was given a silver medal by the Cherokee National Council. He then traveled to Washington, DC in 1828 at the age of 55 and 65 to be honored by President John Quincy Adams and Vice President John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who at that time was becoming rich from gold mines he stole from the Cherokees the previous year. Sequoya died in 1840 while trying to find a lost band of Cherokees in northern Mexico.

And now for the rest of the story

Scholar John B. Davis has correctly pointed out that there are very few primary documents which collaborate facts of Sequoya’s life. 17 As seen in the preceding text, the official histories of Sequoya often conflict with each other and with the actual history of the times, to the point of being ludicrous. The only fact that can be stated with absolute certainty is that a man named George Gist was presented a silver medal in 1824 by the Cherokee National Council. The word “Sequoya” was not on the medal.

Some of the more obvious conflicts involve where Sequoya lived, his age, his physical condition and his trade as silversmith. How could a 43 or 53 year old man, who was too lame to farm or hunt, participate in the vicious combat of the Red Stick War? If he was anti-white, why would he go to war on their behalf against his Creek neighbors just over the other side of Lookout Mountain? How could he have learned to be a silversmith, if he always lived on a remote Cherokee farmstead with a single mother? Wills Town was one of the last hideouts of the Chickamauga Cherokees. That means that if he lived there, Sequoya was a Chickamauga warrior. In that case, he was not a great admirer of European civilization and potential wealthy Caucasian patrons for his silverware were over 200 miles away.

One thing else is quite obvious about the conflicting histories of Sequoya. Most were written by people, who lived hundreds of miles from Sequoya’s original home, and who probably never stepped on earth that Sequoya walked on. They share a complete cultural amnesia of the indigenous Native American tribes that lived in the Southern Highlands before the Cherokees . . . and still lived around them in the early 1800s.

The diverse descriptions of Sequoya strongly suggest that Caucasian historians have assembled descriptions of several men, who lived during the same era, and combined them into one person. It is more probable that the George Guess who fought for Andrew Jackson was either another man other than Sequoya, or Sequoya’s son.

In 1971 Traveller Bird, a Kituwah Band Cherokee, who claimed to be a direct descendant of Sequoya, published, Tell Them They Lie: the Sequoya Myth. 18 Virtually, all of the Kituwah Band version of history is in direct conflict with the mainstream histories of Sequoya. In Bird’s version, Sequoya, was a full-blood Cherokee, who was born in the town of Taskegi (Tuskegee) in North Carolina.

Bird states that as such, Sequoya was a member of the Tuskegee Clan, not the Paint Clan. His real name was Soguli, which means “horse” in Cherokee. That is very close to s’gili, the Cherokee word for witch. He insists that the images of Sequoya are of another man, who was used to impersonate Sogwili. This man was illiterate. It is a fact that the man presented to whites as “Sequoya” never demonstrated his writing system in front of them.

The site of the town of Taskeke (Taskegi in Cherokee) that was described in Prayer we will give… and often is at the foot of the mountain range where Juan Pardo discovered silver ore. Taskegi was a half day’s horseback ride to the ancient Spanish silver mine described in The Lost Silver Mine. About five miles east of Taskeke was the capital town of Chiaha, where Juan Pardo built a fort and left behind a garrison. 19 The inscribed memorial of a Sephardic wedding in 1615 is 12 miles west of the site of the town of Taskeke, and 12 miles east of the site of Chota, where Sequoya spent his youth. (Calculations made by GIS software.)

Bird’s description of the Taskegi Clan relates directly to this series. He described them as once being a separate tribe that was absorbed by the Cherokees. This exactly matches the historical fact that the Taskegi majority in the Smoky Mountains migrated to Alabama to join the Creek Confederacy in response to Cherokee aggressions, while the minority became a division of the Cherokees.

Bird also said that the Taskegi became the scholars and historians of the Cherokee Alliance. They had their own language (Creek) which other Cherokees couldn’t understand, and also had a writing system. Soquili was trained as a scribe in the Taskegi Clan. Over time, he learned the history of the Taskegi Clan, plus English and Spanish. He was not illiterate and provincial as portrayed in Caucasian-authored stories. Why would Sequoya need to become fluent in Spanish, if the nearest Spanish-speaking town was 400+ miles to the south? Traveller Bird never addressed that issue.

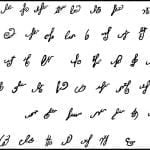

Bird said that the Chickamauga Cherokees used this writing system to communicate with each other. The existence of this syllabary is discussed in several eyewitness accounts of the Chickamauga Wars, but is conveniently forgotten by contemporary historians. Bird said that Sogwili intentionally developed the Taskegi syllabary into the Cherokee syllabary because he did not want whites to understand Cherokee communications.

Bird also stated that the Taskegi learned their writing system from a semi-mythical people known as the Taliwa. The Taliwa wrote on thin sheets of gold. No civilization in the Americas is known to have written their language on sheets of gold. However, this was a custom in the land of the Golden Fleece, the Kingdom of Colchis just north of Armenia and among Armenian Christian book illustrators in the Middle Ages. Of course, Armenia is a long way from Tennessee, so could have no connection with Sequoya.

Taliwa is the word for “town” in the Apalachee language. The Apalachee lived in the gold fields of the Georgia Mountains. In his memoir, Trois Voyages, Captain René de Laundonniére stated that the Indians he encountered in the Coastal Plain of Georgia between 1564 and 1565, possessed gold foil and beads that they had obtained from the Apalache Indians living in the Georgia Mountains. 20

Things a tourist will never be told

Perhaps so as not to offend the Cherokees, contemporary histories on Sequoya, found in immediately accessible media such as online encyclopedias, intentionally leave out some important facts. They are:

- The North Carolina Cherokees bitterly opposed Sequoya’s syllabary and considered it witchcraft. They abducted Sequoya and his wife, sentenced them to death by slow torture for practicing witchcraft and were in the process of torturing the couple to death, when a troop of Georgia Cherokee Lighthorse, led by John Ridge, rescued the couple. It was not his wife that accused Sequoya of witchcraft and burned his records. The Cherokee syllabary was ultimately taught to North Carolina Cherokees in the late 20th century as part of a tourism & economic development program.

- Sequoya is the Cherokee way of writing and pronouncing the Creek word, sekuya. It literally means “excrement,” but in the 1700s its idiomatic meaning was “pariah, scum of the village or war captive.” 21 Sequoya’s mother could well have been a Creek war captive, not Cherokee royalty. For some unknown reason, she was also considered spiritually unclean and therefore, Cherokee men would not marry her.

- Elias Boudinot of the Cherokee Phoenix lied in his article about the introduction of the syllabary. The syllabary created by Sequoya, was not the syllabary adopted by the Cherokee Nation and in use today. Sequoya’s original syllabary was almost identical to the Cyrillic script used by Christians in eastern Turkey, Armenian and Georgia until modern times. Elias Boudinot thought that Sequoya’s letters would seem too “alien” to Caucasian Americans, so he and missionary Samuel Worcester changed the original symbols to look more like the Roman style letters in the English alphabet. That original syllabary is important evidence that the Tuskegee Creeks in the Smoky Mountains had direct contact somewhere in the past with Christians from eastern Anatolia, Armenia, Georgia or northern Mesopotamia. It seems odd that Cherokees, living outside the boundaries of the Cherokee Nation in North Carolina, who were under the influence of Protestant missionaries, would object to a writing system whose first use was the printing of a Cherokee language Bible. On the other hand, if the mother of Sequoya was a s’gili or witch, that would immediately place him under suspicion. It may or may not be a coincidence, but several Cherokee words association with bewitching and casting spells include the root word “jinn,” which happens to be the Turkish word for a spiritual being. The Anglicized word, jinni, comes from that Turkish word.

Citations:

- Williams, Samuel C., “The Father of Sequoya: Nathaniel Gist“. Volume 15, No. 1. Chronicles of Oklahoma, March 1937. pp. 10-11.[↩]

- Official history of Sequoya, Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma web site.[↩]

- Williams, Samuel C., “The Father of Sequoya: Nathaniel Gist“. Volume 15, No. 1. Chronicles of Oklahoma, March 1937. pp. 10-11.[↩]

- Davis, John B., Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. 8, Number 2. “The Life and Work of Sequoya.” June, 1930.[↩]

- “Sequoya” – The Encyclopedia of Alabama[↩]

- “Sequoya” – The Encyclopedia of Arkansas[↩]

- “Sequoya” – The Encyclopedia of Alabama[↩]

- Official history of Sequoya, Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma web site.[↩]

- “Sequoya” – The Encyclopedia of Arkansas[↩]

- Bob Benge – Wikipedia.[↩]

- “Sequoya” – The Encyclopedia of Alabama[↩]

- “Sequoya” – Wikipedia[↩]

- “Sequoya” – Encyclopedia of Alabama[↩]

- Davis, John B., Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. 8, Number 2. “The Life and Work of Sequoya.” June, 1930.[↩]

- Boudinot, Elias, Cherokee Phoenix newspaper – (1828-08-13). “Invention of the Cherokee Alphabet”.[↩]

- “Sequoya” – The Encyclopedia of Arkansas.[↩]

- Davis, John B., Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. 8, Number 2. “The Life and Work of Sequoya.” June, 1930.[↩]

- Traveller Bird, Tell Them They Lie: The Sequoya Myth (Los Angeles: Westernlore, 1971).[↩]

- Bandera, Juan de la, Relacion de la Florida, 1569; pp. 268-269 of the Ketchum translation.[↩]

- De Laudonniére, René Goulaine, Trois Voyages, L’histoire notable de la Floride, contenant les trois voyages faits en icelles par des capitaines et pilotes français, 1586.[↩]

- Martin, Jack B. & Mauldin, Margaret M., A Dictionary of the Creek/Muskogee, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.[↩]