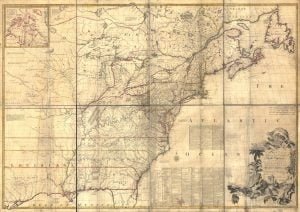

The Mitchell Map remained the most detailed map of North America available in the later eighteenth century. Various impressions (and also French copies) were directly used to help establish the boundaries of the new United States of America by diplomats at the Treaty of Paris (1783) that ended the American Revolutionary War. The map’s inaccuracies subsequently led to a number of border disputes, such as in Maine. Its supposition that the Mississippi extended north to the 50th parallel (into British territory) resulted in the treaty using it as a landmark for a geographically impossible definition of the border in that region.

It was not until 1842, with the signing of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, that the U.S.-Canadian border was clearly drawn from Maine to the Oregon Country. This finally ended ambiguities resulting from use of the map to define American territory at the end of the Revolution.

Since Mitchell’s main objective was to show the French threat to the British colonies, there is a very strong pro-British bias in the map, especially with regard to the Iroquois. The map makes clear that the Iroquois were not just allies of Britain, but subjects, and that all Iroquois land was therefore British territory. Huge parts of the continent are noted as being British due to Iroquois conquest of one tribe or another. French activity within the Iroquois claimed lands are noted, explicitly or implicitly, as illegal.

In cases where the imperial claims of Britain and France were questionable, Mitchell always takes the British side. Thus many of his notes and boundaries seem like political propaganda today. Some of the claims seem to be outright falsehoods.