My first interpretation of these manmade features was that I had stumbled upon the ruins of an old gold mining operation. Union County, where Track Rock Gap is located, was the last county in Georgia where commercial gold mines operated. They had finally closed in the 1950s. The ruins seemed to be from a much earlier era, however. I hoped that they might prove to be vestiges of 17th century Spanish Sephardic colonists.

My search for architectural proof of the Sephardic gold miners had begun six years earlier. In 2005, I found the ruins of rectangular fieldstone foundations near the Tuckasegee River, west of Sylva, NC. Later that summer I stumbled upon similar ruins along a remote creek in the Unaka Mountains that divide North Carolina and Tennessee, west of Murphy, NC.

Those discoveries eventually led to a friendship with Dr. Brent Kennedy of Wise, VA. Kennedy had become nationally known for his research into the origins of the Melungeon people of the Southern Appalachians. After receiving my email about the enigmatic ruins near the Tuckasegee River, he immediately mailed me a copy of a British colonial archive which described settlements of Spanish-speaking gold and silver smiths. They lived along the Tuckasegee River until 1745, when the Cherokees first entered that region and drove them out.

Kennedy planned to drive down that winter and visit the ruins. Unfortunately, in December of 2005 Kennedy was permanently disabled by a massive stroke. We were never able to meet in person.

In early spring of 2010, I was camped out in Graham County, NC. Graham is located in the extreme western tip of the state, walled in by the Unaka, Smoky and Snowbird Mountains. I befriended several Snowbird Cherokees. They told me about a boulder with Latin words on it that was located near the top of the Unaka Mountain Range on Hoopers Bald. The Cherokees thought that it was proof that the de Soto Expedition came through the Cherokee Nation. I decided to be discrete and not tell them that absolutely no Cherokee words were recorded by the chroniclers of the de Soto Expedition.

Nevertheless, in case there really was an old inscription on a rock in the North Carolina Mountains, I drove west to the Unaka Range. I found the boulder at about a 5,400 feet elevation. On it were inscribed the words, “PRE DARMOS CASADA – SEP 15, 1615.

A little more detective work revealed that several people in the county knew about the inscription. A few years before, a Graham County historian, named McClung, had photographed the rock and taken the picture to the McClung Museum in Knoxville, TN. The director of the University of Tennessee’s Department of Anthropology had declared the phrase to be Latin, and mean, “Land that we will hold and defend.” He said it was legal claim to all the land that could be seen from that high point.

The inscription was not Latin. In fact, it bore no resemblance to the Latin words that would have a meaning as the anthropologist described. The phrase was Late Medieval Castilian. It meant, “Prayer we will give, married September 15, 1615.”

There was something very special about one of those words, however. “Pre” was a medieval Iberian word for prayer. However, by the 1500’s Spanish Catholics began using the word “suplicacion” for prayer, to distinguish the superiority of their prayers from those of the Jews. Sephardic Jews continued to use the word, “pre.” The inscription was a memorial to a Spanish Sephardic marriage in 1615. In Jewish sacred literature, couples may legalize their marriage with such inscriptions, when there is no rabbi available.

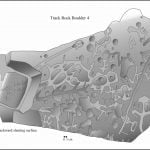

I became increasingly convinced that the ruins of an Early Colonial Period Jewish village were at Track Rock Gap. On one of the petroglyphic boulders at Track Rock Gap was the inscription of a Jewish girl’s name, “Liube 1725.” The archaeological artist or archaeologist, who recorded that name on drawings prepared for the U.S. Forest Service, completely missed the significance of the name, Liube. It is an Ashkenazi Jewish female’s name that was never used by European Christians. It is derived from the Eastern Slavic word for “love”.

A brief visit to the Union County Historical Society’s office in the Old Courthouse did not provide any more insight on the fieldstone walls. I asked the men doing genealogical research there, if they had heard of any Spanish or Jewish artifacts being found in the vicinity of Track Rock Gap. They smiled, and looked at me like “I was tetched in the head.” One grinned, and told me that there were a few Cherokee graves at Track Rock Gap, but the only Spaniards, who had ever been near there were illegal aliens from Mexico . . . “and the cops have just about gotten rid of them.” Everybody in the room laughed, except me. Little did they know how prophetic that joke would become.