By way of diversion from the un-enlivened processes of pure ethnological description, a scene from the work of a day of one of the hunters (Paul Miles) will convey a picture of life at Pamunkey and help to give a background for an understanding of living conditions.

A chilly northwest wind is blowing down the Pamunkey late in the afternoon when we leave the village facing the rays of the setting sun, and embark in Paul’s canoe, paddling toward the mouth of a sinuous lagoon called Great creek. This flows out of the big swamp at the western end of the territory which the Pamunkey still call their own. Its fastnesses of swamp-gum, magnolia, and swamp-oak at high tide are flooded with the coffee-colored waters of the river. At low tide, which here drops between two and three feet, the turbid waters leave a tangle of roots and hummocks of indescribable muddy congelation in tussocks some eight or ten feet across, from the top of which rise clusters of gums, oaks, and other trees. Some of their trunks tower fifty to sixty feet above the muddy floor of the swamp, while a thicker but lower growth shuts off the swamper’s view beyond a distance of twenty feet. In this memorable and gloomy vaulted fastness of malaria, tenanted only by the creatures of solitude, the Pamunkey hunters have pursued the chase for many centuries. Wild turkeys, the noblest of game birds, ducks, the bald- eagle, geese, deer, raccoons, opossums, otter, mink, and muskrat have survived generations of keen trappers. Their ranks have ever been recruited from the flocks of birds and mammals which still make their periodic visits; one might almost say migrations, through the tidewater region. The great blue heron, the white young of the more southerly herons, and most numerous and omnipresent of all, the great barred owl are the permanent denizens of these dank recesses. When we leave the open river with its cheerful ripples lapping the sides of our canoe, and the gray clouds banked in the sky now to the east over the Chesapeake, the ”great salt water” of the Indians, we convert our paddles into poles and poke our way over mud bars into Great creek, at each prod loosening a swirl of reddish mud which rises ever thicker through the opaque current and now and then sending ahead in muddy ripples some fish that is startled by our advance into his roily domain. A smell of saturated mud, drenched dead wood and moldy leaves comes to us as the gas bubbles rise to the surface when released by our shoving-paddles.

As the tide is low, the whole floor of the swamp is carpeted in places with sodden sedge grass, while everywhere lie matted leaves coated with dried brown mud. Brown is the dominant color: brown are the tree trunks, marked distinctly to the high-tide level; brown is the glazed mud and ooze, and glassy water in here where no wind strikes it. Two or three bends of the lagoon carry us out of view of the river and the edge of the swamp. On all sides the drainways of the interior have cut through the floor, leading in slimy slopes to the edge of the water. Innumerable tracks of small animals are to be seen at each sluice muskrat, mink, otter, with here and there one which the Pamunkey remarks in a whisper to be raccoon, and finally, farther in, those of turkey. The gun which has rested in the bow is now loaded and taken in hand ready for work as the guide, now aroused to the importance of his task, plies his long oak paddle from the stern and forces the canoe over or around the mud-bars and ooze-shoals which are left nude and brown for three hours more before these inland tides will again cover them. ”Now if you see anything jump up, I want you to cut him down.” ”I will,” I whisper in reply. Only the drip of a dozen drops from the evenly swaying pole-paddle announces our entrance into the solitude. How busy the Pamunkey huntsmen are in their swampy domain, when at every bend we see one of their deadfalls for mink, coon, and otter, now soaked, mud-coated, and weed-clogged as they are exposed by the ebb tide. ”All right,” I whisper again as the steersman gives a “shiver” from his seat in the stern, the Pamunkey way of saying without words, ”Watch closely, something moving!” A distant rustle of twigs on the right in a gum cluster is the first cause of alarm. I ”shiver” once in my seat in response and he turns the canoe with a silent shove to the right so as to throw me about facing the noise, lest in giving a sudden shot I upset the canoe. What will it prove to be, a deer aroused, or will a turkey burst away? A furtive rustle, a noisy flutter, and a white-throated sparrow pops into view with a piquant air; flutters loudly enough, it seems, to disturb the silence of the swamp, and we resume our stealthy passage into another arm whose slimy banks rise several feet on both sides. Here the creek is hardly more than fifteen feet wide. On both sides are the ski·′tðnðs, the “red berries” in the Pamunkey dialect, upon which the turkeys feed. On all the water-gums are showing small isolated berries. These likewise furnish food for the turkeys. While the Pamunkey have completely forgotten their native tongue, it is not surprising to find that in their natural-history and hunting vocabulary some last Indian words survive.

Another “shiver” from the steersman warns me again of game detected. At the same instant a form moves on the horizontal branch of a monster gum-tree whose roots form a vault of mud-coated columns leading to its massive buttress. “Let him have it!” No, it is only the spirit of the swamp, the barred-owl, which now turns his ogreish head about and drops off to another rampike in noiseless flight.

Five minutes later we hear his vacant whoo-oo farther off, and an answer from his mate, still more filmy and remote, filling the mind with the sense of hush and distance. The sound is indeed fitting to the exotic atmosphere of the swamp. Now, as it is nearing sundown, we look for a motionless pool to stop in and listen from, to harken for the roosting calls of the hens or possibly to hear the rush of wings as the great birds fly to roost on some limb fifty feet above, where they will crane their necks in all directions for about twenty minutes before contracting their great bodies to the smallest compass, to simulate the knots on the gums, and tuck their heads under wings to sleep like any secure barnyard fowl. This is the critical time. Every sharpened sense of both hunters and turkeys is keyed to action. ”There goes one!” A whisper and powerful ”shiver” convey the observation. Too far away; he has bolted for some inaccessible thicket and we see no more of him.

Now it is to wait twenty minutes in our position while the Indian holds the canoe still by poking his pole-paddle into several feet of submarine mud. There is not a sound. Three or four birds fly high, probably woodpeckers; a distant hound’s yelping proclaims another Indian somewhere on the move.

It is now time to turn back, as darkness sets in heavily with a penetrating damp that will even defy the strenuous paddling necessary when we emerge again upon the open river. The canoe is swung around and the Indian poles her swiftly but silently along until the evening gleam on the horizon shows that we are nearing the edge of the swamp. We tarry and enter yet another draw to examine the high tree-tops for birds that may be roosted there, for at this darkening half-hour the birds are all off the ground. Several suspicious clumps turn out to be only knots, or gnarled lightning-blasted branches, or clusters of dense mistletoe. Back to the river again, as the game is over for tonight. A crescent moon above the evening star is framed by bulky cloud masses. The wind has ”lulled” and we make for the landing beach on the reservation shore where for generations Pamunkey hunters have likewise drawn up their canoes after having engaged in the same performance as that which we have just been through.

Pamunkey Turkey Calling

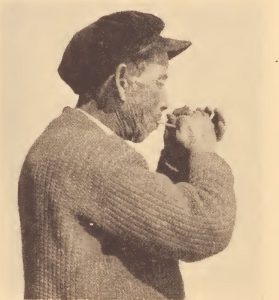

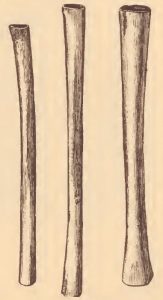

In another method of turkey-hunting the Pamunkey resemble the eastern Algonquians in general; they call the game to them by imitating their cries. Although the deer are not known to be so dealt with, since they are attacked by the drive, the wild turkey being susceptible of imitation is successfully lured within range of the weapons of the concealed huntsmen. The turkey being possessed of gregarious inclinations is skillfully lured by an instrument, called a turkey ”call” or “yelp,” manipulated with the lips and hands. The article so employed is a section of the secondary wing-bone of the bird itself. Sections of bone about five inches long are kept for this service (figs. 62, 63), though not infrequently a similar length of cane (Arundinaria) is substituted, and I have collected a specimen of the same consisting of a four-inch section of hollow ash twig in fact a pipe-stem. Let us observe the procedure with John Denis, a Pamunkey hunter and guide of long experience.

Toward evening, going out into the oak and gum swamp where turkeys are known to be, a flock is finally flushed by the noise of advance. The hunter remains quiet; it may be for half an hour. Soon a call, or ”yelp,” is heard from one of the birds of the dispersed flock calling the others together, and some of them answer.

The hunter then works noiselessly a few feet toward them, if possible. He crouches low behind the buttress of one of the big gum trees and tries a “yelp” with his wing-bone tube, his weapon close at hand. If he gets an answer he tries again in a minute, tuning his ”yelp” to serve as a means of drawing the bird to him, by the seductive chirp repeated three times to the scattered birds, which means, ”Here I am; where are you?” Should he make the slightest break or mistake in his tone, the whole flock would be alarmed and tumultuously fly off. The enticed bird, however, is completely deceived and steps forward, cranes its neck to one side, then the other, clucks, and peeks cautiously for a suspicious movement in the direction of the call. Now is the critical moment to render the call-tone in dulcet pathos. Bang! Off goes the flock into the heart of the swamp again.