Report of Special Agent C. W. Wood on the Indians of Yuma reservation, Mission-Tule Consolidated agency, San Diego County, California, January, 1891.

Name of Indian tribe occupying said reservation (a): Yuma.

The unallotted area of this reservation is 15,889 acres, or 72 square miles. This reservation has been surveyed and subdivided. It was established by executive order January 9, 1884.

Indian population June 1, 1890: 1,208

The Yuma Indian reservation lies along the Colorado River, and embraces 45,889 acres, of which 4,000 acres are tillable. The tract actually cultivated by the Indians is the narrow belt lying near the Colorado River, called the “overflow lands”.

The tribe numbers, by the, comet for the Eleventh Census, 1,208: males, 659; females, 549.

The Yuma Indians mostly live upon their reservation, although about 300, having become dissatisfied with Chief Magill, settled on the Arizona side of the Colorado, in and near the city of Yuma.

These Indians are much more fortunate respecting their reservation than most of the semi-nomadic tribes. Abundance of water can always be obtained from the river or by digging shallow wells from 6 to 20 feet in depth in the adjoining low grounds. The river abounds in fish, the principal kinds being carp, a kind of whitefish resembling mackerel, and salmon trout. These are obtainable the year round and from so large a proportion of their food that the Yumas are very commonly called ”fish Indians”. They also sell many fish to the whites. Large game is almost extinct. A few deer are killed annually, and cottontails and jack rabbits are quite numerous. Quail are abundant, and also wild ducks. These the Yumas kill with bow and arrow, as they have few guns.

Very little stock is possessed by this tribe. The destructive practice of cremation is an obstacle to an increase. They have a few horses, cattle, mules, and bullocks, the latter being used in freighting to the mines. They raise some poultry, but, as they provide no protection for it, the coyotes and other animals get the benefit of it. They receive 50 cents per dozen for whatever eggs they gather. They cultivate but little ground, raising barely enough wheat, barley, corn, and vegetables for their own use. They always plant after an overflow of the river, without disturbing the, soil otherwise than by making holes in which to place the grain and seeds. They raise 2 kinds of brown beans, also very large and sweet squashes, which they can easily sell at 50 cents each, whenever they can be persuaded to part with them. Large watermelons and muskmelons grow in great profusion, which in their season are almost the exclusive article of food. Mesquite beans, growing wild on the reservation and affording a very palatable food, form a large part of their provisions at all times and become their main reliance for breadstuff when the Colorado fails to overflow. The vicinity of a city, although a small one, affords the Yumas many resources by which they might secure a comfortable living if they were inclined to industry. Cay and wood are always in demand. These commodities have to be “packed” over the river on the heads or backs of the Indians, and most of this work is done by the women, whose loads are double the size of the few carried by the men. The men find a good demand for their labor in mines, on ranches, in work about the city, as deck hands on the 2 river steamers, and in miscellaneous jobs. The women are sought to render services in the city houses in addition to the “packing” referred to. The Yumas are content with little, and that little is easily obtained. They loiter and spend much time in and about the city, where one may frequently see a hundred or more at one time. Those who have given theirs employment say that they are very intelligent and learn new work and the use of new tools very readily. There is abundance of work, good pay, fair abilities, but little disposition. Within a year they filled a contract for 800 cords of mesquite wood at $3 per cord, but declined another contract for 1,000 cords at the same price. Thousands of cords can be cut on the reservation within easy hauling distance of the railroad switch on the California side of the river, but the Indians do not begin to meet the demand for wood for household use in the city. The climate of Yuma is conducive to the Indian’s indolence. The summers are very hot. The highest temperature reached in 1890 was 1150 in the shade, on July 22. The minimum for the week ending July 28 was 810, and the mean heat for the same week was 830. The lowest temperature of the winter of 1890-1891 was 270, on January 10, when a shell of ice formed on standing water, but no injury was done to orange, lemon, pomegranate, and other trees of semitropical character, and most of the Indians were barefoot daring that week. 1

The Yumas now dress generally in the costume of the whites, though somewhat scantily. They usually go barefoot and barehead the year round, though in warm weather they put “turbans” of river mud upon their heads in order to keep them cool.

In regard to clothing, within 3 or 4 years the men wore only the “gee-string” and the women aprons made of tassels of soft bark. The change is owing mainly to the action of the superintendent of the government school on the reservation, in forbidding adults to come to the school for any purpose unless properly clothed. When going to the city with their burdens the women often wear sandals of sole leather rudely shaped to the feet and tied on with sinews.

The Yumas are considered untruthful and notoriously unchaste. The girls are debauched early by the young, Indians and the low whites. The fact of prevalent immorality is evidenced by the syphilitic taint in the blood of the children. They are subject to various forms of lung complaints. Many of them are pitted with smallpox. They are slow to apply to the physician at the fort, and refuse to take any unpalatable medicine. There is very little intemperance among them, since intoxication is promptly followed by 20 lashes, according’ to their own law. They are a filthy people covered with vermin. Mothers eat vermin taken from the heads of the children, saying that it would not do to kill them, as they are a part of the person.

The Yumas are inveterate gamblers, even the schoolboys providing themselves with packs of cards. The superintendent and teachers of the school take away all the cards they see in the hands of the boys, but teachers are helpless when the children are allowed to play freely out of school. The adults bet on foot races, cards, and many other games.

The Yumas are physically a well-developed race; the men are generally tall and somewhat slender. Both men and women paint their faces. The women are bent and prematurely aged by hard labor and family cares.

From a careful observation of the children in the different class rooms, and counting the unmistakable full bloods and mixed bloods, it is safe to say that at least 20 per cent of the children are half-breeds. One hundred and forty-two names are enrolled on the school record; average attendance, 118. The children exhibit the average intelligence, docility, and good temper of the children in other tribes. The discipline in the class rooms is of a superior character.

The religious ideas of the Yumas can be stated in a few words. They do not believe in either good or bad spirits, but fear the dead and believe in witchcraft. They burn the property of the dead. They never rebuild on the spot where a house has been burned because of a death in it. Such sites are frequently to be found on very desirable locations, and in one instance a cook stove was found in fair condition in spite of its fiery ordeal; but nothing could induce a Yuma to appropriate it, even to sell it for old iron. After several deaths have occurred in a rancheria, or village, the Indians burn the remainder of the houses and build in a new location. This tribe can not properly be called even nominally Catholic, although the only instruction they have received has been in the ceremonies and doctrines of that religion. This instruction has been mostly confined to the children.

They believe in good as well as bad witches, and if a good witch says of any person “that is a bad witch”, it is his or her death warrant.

The Yumas, in accordance with the custom of all the so-called “River Indians”, cremate their dead. The bodies, if buried, would be exposed by the overflows of the rivers and devoured by wild beasts.

On the morning of December 9, 1890, the enumerator witnessed the, cremation of the body of a man who had died just before daylight. The bodies are burned as soon as arrangements can be made. As he approached the place of cremation the wails of the mourners could be heard for nearly a mile, The funeral pyre was about 4 feet wide, 6 feet high, and 8 or 9 feet long, consisting of logs of wood which had been built up around the corpse, and the clothing and bed clothing of time deceased had been piled ripen the body before the logs were placed over it. The top was piled with bead necklaces and collars and other valuables in great profusion, and on the ground in a circle about time fire were scattered corn and beans, not placed upon the pyre for fear of smothering the fire. Great piles of ashes of burned clothing were also visible on and around the blazing pile. All these things were offerings by mourning friends. A squaw stood at the foot of the pyre, as near as the heat would allow, overhauling a box of provisions which had been the property of the deceased, the contents of which were cast into the fire one after another, and finally the box itself. Them squaw stripped herself of all but a scanty skirt and threw her garments upon the fire, then joined the chorus of mourners. Another squaw stepped into the circle, having a bag of corn, probably her entire stock for the winter, and staggered part way around the circle, scattering the corn as she went. Having completed her corn offering, she grabbed a younger squaw by the arm with both hands, and, bracing herself, stuck her chin up in the an and began her contribution of subdued howl and wail, the sound of which is like the moaning and wailing of children when crying for something they can not get. It seems entirely mechanical, as the mourners often stop and chat with one another and then make a fresh start. The squaw who had scattered the corn, after wailing a few minutes, stripped off her clothing and at it into the blaze. A fine-looking, well dressed Indian standing near her took off everything but drawers and undershirt and consigned them- also to the flames. It was early in the morning and quite cold, yet 15 or 20 men and women were squatted around the pyre in a nearly nude condition. The burning of clothing is obligatory upon the relatives of the deceased, and friends show their regard for the dead by the voluntary offerings they make. Finally the dead mans home was, burned with everything in it and upon it, for on the roof were great baskets of mesquite beans and corn. Every scrap of property that could be destroyed or damaged by fire was burned, even the money he possessed being thrown into the furnace of destruction.

This magi left a wife and 2 children, who were not only bereaved of their natural protector, but were also left homeless, naked, and destitute of food. This cremation of property is as inexorable as a vow to perpetual poverty, and a serious obstacle to all advancement or the tribe.

Once every year a mourning feast is held to which other tribes are invited, and great stores of provisions and fancy and valuable articles are collected. After the feast is over everything remaining is burned, and this general, conflagration, following all the destruction incident to private mourning, is also a great factor in promoting poverty and degradation. It may bethought that the children will be educated to look upon such a destruction of property as a wicked waste, but, on the contrary, it is a great treat for them to learn of a cremation, and they desert the school en masse to attend it unless locked in the schoolrooms. The teaching and example of their parents prove more powerful than the instruction they receive in school. This burning of property explains why the Yumas have so few animals, since they must all be killed at the death of the owners. It is also evident that sick visitors are not desirable among them, as the house in which a death occurs must be burned.

Review of the Facts Concerning the Pumas

A review of the facts ascertained about the Yumas does not, on the whole, reveal a very hopeful outlook for the civilization of this tribe. Mentally they are up to the Indian average, but morally they are of the lowest grade of barbarians. What can be done for them? If left to themselves the tribe would be depleted by the diseases consequent upon promiscuous sexual relations. While they are singularly temperate in thinking, owing to the severity of their own laws in regard to intoxication, no advancement is possible for them, even as Indians, without a radical change in some of their institutions and habits. In addition to the difficulties in the way of civilization incident to mere barbarism in general, the Yumas have peculiar customs which can not be mollified but must be abolished. For instance, as Indians, they can not accumulate property beyond one life interest because of their method of cremation. The destruction of the property of the dead is far worse than the practice in some tribes of killing one or more horses and the offering of food, clothing, and weapons. All the personal property of the dead must be utterly consumed by fire, or if there is anything noncombustible it must at least pass through the “baptism by fire” and be damaged as much as possible. House, food, clothing, money, weapons, and animals, all must go. The site on which the house stood must never be used for another building or be cultivated, so that so much real estate is alienated from use forever. If the government should build a good farm house for each Yuma the erection of a small hut for use in case of serious illness and destruction in case of death would not, as has been suggested, meet the difficulties in the case. This remedy would not avail because superstition forbids the use of any property that has belonged to the dead. However successful, then, any individual Yuma might be in any line of business or employment his family would profit thereby during his lifetime only. What can be done to break up such a practice, founded, as it has been, upon superstition? The question is a serous one, as other tribes along the Colorado River, called River or Fish Indians, like the Yuma’s, observe this same custom.

Their belief in is a worse superstition than the other, since it involves the destruction of life. Some believe that for every death from natural causes a murder is committed and that the charge is made secretly to the chief who orders a “committee” to kill the accused. It is supposed that they choose their own time and method of destruction, and that no one is aware of the accusation or of the appointment of the executioners, because publicity would defeat their object. All of the Indians are believed to know that some one is liable to be singled out as a victim, yet no one but the members of this aboriginal “star chamber” knows who has been selected, and all ties are ignored in both accusation and execution. It is reported that a young squaw lost her baby, and, without any regard to her bereavement as a mother, she was accused of having bewitched her infant to death, and that two young Indians, one of them her own brother, were appointed to kill her. The supposed murderers were arrested, and, although the brother committed suicide in prison, legal evidence could not be secured to convict the survivor, and he was discharged. Witnesses, if there are any, dare not give their evidence lest they should be killed. The speediest way to end this reported practice, will be to abolish the chieftainship. With no chief to order the assassinations they would cease, as no one would then take the responsibility of such deeds. The chief has absolute authority over his people, and he maintains it by threatening all kinds of bewitchments if they do not obey him in every respect, No one can tell how many of these murders take place in remote parts of the reservation. Groups of houses (rancherias) are scattered over a territory from 2 to 4 miles wide and go in length, and lying along the Colorado River. Frequent rumors of Men or women being killed on the reservation are circulated, but the facts can not be ascertained, the Indians give such evasive, replies to all questions on the subject. Deaths, and cremations take place near the city, and are not known to the whites in time to witness the cremation of the bodies. The Indians do not like to have white spectators.

Another fatal accusation is said to take place among them which does not involve a related death by disease. If a reputed “good witch” declares any man or woman to be “bad witch”, an exterminating committee, is believed to be appointed, which performs its duty promptly and effectively. A company of soldiers stationed on the California side of the river, with a line of sentinels to prevent the free passage of young Indian girls into the city, might preserve them from the dangers of the city, which they now freely court.

The education of the Yuma boys and girls in the government schools on the reservation has proved successful, demonstrating that Indian children can be taught all the branches of a common school course. One fun-blooded Yuma girl about 17 years of age speaks, reads, and writes both English and German, and paints with time average talent of white girls of her own age. She is a teacher in a seminary for white children, and in dress, manners, and refinement would hold a good position among the young lady graduates of any white institution. Suppose Yuma girls have passed through the school with credit to their teachers and themselves intellectually, and have learned the various arts of housekeeping, ordinary sewing, and knitting, and attained considerable skill in fancy work and embroidery; then add to these attainments a practical knowledge of Christianity. These girls must usually return to their tribe, to degrading influences. Their school is no longer a home or protection to them. Such is the post-graduate “course” awaiting the 75 or 80 Yuma, girls who are now being educated in the government school on the Yuma, reservation. On leaving school they will be nothing but Indian girls. The direful possibilities before them are illustrated in the case of a girl, before her ruin the most beautiful girl in the tribe, but at the age of 15 dying under the most loathsome circumstances. She was not a graduate from the school, but even if she had been her fate would not necessarily have been different. The windows of the dormitories or both sexes in this school are fitted with iron rods to prevent egress or ingress by the pupils, a feature found in the construction of other Indian school buildings.

Indian schools return their graduates to the same tribal environments from which they were taken. The schools are not responsible for this. The statement has lately been made public that young Indian mechanics have no tools with which to work at their trades. This may lead to benevolent provisions to, supply the necessary conveniences. There is, however, a worse, lack than that of tools, namely, employment. Among the Yumas the greatest skill, accompanied by a complete outfit of tools, could not create work. No mechanical trade has any place whatever in the economy of one of their villages. The knowledge of the English language is of no practical use where it is not spoken, nor of arithmetic, where it is not needed, nor of geography where the village and its surrounding territory are their world.

So far, then, in the working of the educational part of the Indian problem, the effect has been, practically, to sandwich some degree of education between layers of barbarism. The children for it few years under existing conditions move in surroundings which are an abrupt and unrelated transition from their past, but without much promise or vital connection with their future.

Yuma Indians

Report of Special Agent W. B. Ferreber M. D. on the Indians of Yuma reservation, Mission-Tule Consolidated agency, San. Diego County, California, November and December, 1890.

Many difficulties attend a search after reliable information concerning the early history of the Yumas, for when a member of the tribe is found willing to talk about the history of his race no reliance can be given his story. They have no system of transmitting their past history and legends. Therefore all accounts will necessarily be fabrications, in which Indian imagination plays a conspicuous part.

It is customary with some Indian tribes to select aged and respected male members to relate to younger men at their annual festivities the legends and remarkable occurrences to time tribe in the past, and thus a traditional history is preserved; but this is not so with the Yumas, who regard the past as dead to theirs, and really try to forget it, not understanding how it could be interesting or instructive in their future.

In the latter part of the seventeenth century Catholic missions were established along the Colorado River by Jesuit priests, among whom were Fathers Escelente, Ensebio, and Francisco. In the year 1774, Don Juan B. Ainsa, a Spanish officer, in the company of it few priests, visited these missions, and established it new one on a point of laud in sight of the present Yuma reservation, which was called “La Concepcion”, and it is supposed that the name Yuma was then given to the Indians residing within its jurisdiction.

Yuma Reservation, Mission-Tule Consolidated Agency, California

The Yumas first came into prominence during the gold-fever excitement in California. Their raids on overland emigrants traveling westward then became so notorious and their murders so frequent that in December, 1.850, Major Heintzelman, of the United States army, who hail previously been stationed at San Diego, California, acting under instructions, established a military post on the west side of the Colorado River, and called it after the name by which the Indians were when known, Fort Yuma. In the early fifties several battles were fought between the soldiers and the Yumas. It was in these battles that Paschal first acquired prominence and exhibited qualities of generalship that surpassed those of the Apache Chief Geronimo but the difference in the character of the surrounding country produced different results. Geronimo had the fastness of the mountains in which to take refuge and rest, while Paschal was surrounded for many miles on all sides by the sandy and barren desert, destitute of anything for horse or man. In the year 1853 a treaty was made with the Yumas, in which Paschal was required to kiss the holy cross, which he esteemed with due Catholic reverence, and thus ceased all contentions. Since then the Yumas and the Cocapolis, Indians from Lower California, have fought several battles of more or less magnitude.

The Yumas occupy a reservation, established by the government in 1884, of about 15,889 acres, which is situated in the southeast corner of San Diego County; California, in the valley of the Colorado River, the river forming its eastern boundary. Most of the reservation could be, cultivated if water for irrigation could be procured. The valley lands are alluvial deposits. The, soil is rich, and only water is needed to make it blossom as the valley of Hebron. The government is now considering the purchase of pumps to raise the water from the river, and the construction of a canal to convey it upon the lands.

The expense of the contemplated facilities for irrigation will be considerable, but they, joined with practical instructions in the methods of farming, will give these Indians a fair chance and afford them an opportunity to redeem themselves from the degradation into which they have evidently lapsed. Upon the reservation grow naturally the mesquite and screw beans, arrow willow, and sagebrush, but with water in this climate all semitropical fruits, both citrus and deciduous, admit of successful and profitable cultivation.

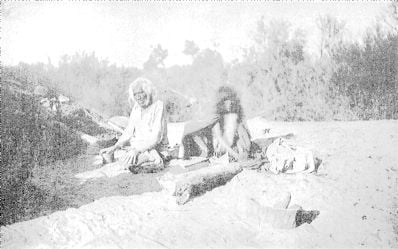

The crude methods of cultivation employed by the Yumas at present depend for success on the uncertain annual inundation of the Colorado River. It sometimes happens that the rise in the river is insufficient to overflow the banks; then the Yuma harvest is a total failure and the Indians are forced to extra exertion to keep from starving. The overflow usually occurs in May or June, and when the water has subsided the Yumas plant their crops by digging holes about 3 feet apart and about 10 inches deep in the wet ground, into which they drop a few grains of wheat or corn, cover with earth, and nature is relied upon to do the rest. A crop of wheat will range from 100 to 300 hills. No uniformity is practiced in planting in rows. When the wheat is in the milk the Indians begin to gather and eat it, and frequently when harvest time comes they have no grain to gather. The few who do let their grain mature thrash it out by heating the heads over the edge of a stone vessel. In this way they may gather from 1 to 3 bushels. A Yuma harvest is practically limited to melons, squashes, pumpkins, corn, wheat, and beans. In addition to these, nature provides these people with the mesquite and screw beans, which grow on scrubby trees from 10 to 30 feet high and provide an abundant supply of acceptable food. The mesquite bean resembles our string bean, and ripens in June. The Indians gather them in quantities and store them in willow granaries placed on platforms at an elevation of 4 or 5 feet from the ground. The seeds are useless and are thrown away, but the pods contain a juicy saccharine pulp that is exceedingly nutritious. The pods are ground to meal in metátes and mixed with water, making a sort of mash, which is greedily eaten, or it is crooked over heated stones into a sort of flat unleavened bread, which becomes very hard and may be kept an indefinite period of time.

The screw bean grows in a small bunch of spiral sprigs, about 8 or 10 in number. The normal length of a screw bean is about 1 inch, but it is capable of being elongated to about 4 inches by pulling out the elastic spirals. It is not very palatable, but quite astringent. As a rule, the Pumas do not eat much of this bean food until they run short of melons, pumpkins, core, and other crops. Their wheat and corn are ground in makes, and the flour is made into dough, without yeast, and cooked in various ways. The most common method consists in placing a thin piece of dough on street iron over coals, and with constant turning it is baked into ”tortillas”. Pumpkins constitute a favorite dish, but the watermelon is the great staple article of food. The melon season is about 9 months of the year, and it is prolonged by burying the melons in the sand, where they sometimes keep all winter. “Tuni” fruits of the numerous cactuses are also eaten. Fish, caught from the Colorado, help to satisfy hunger. Their method of cooking fish is novel, but retains all the nutriment and renders the meat delicious. They envelope the fish in moist clay and bake them in covered pits, heated by hot stones, and when finished the clay is broken away, taking the skin of the fish with it.

The Yumas are inordinately fond of candies and sweetmeats, which they purchase from the whites. They also eat moles, gophers, beef entrails, rabbits, venison, quail, wild geese and ducks, and land tortoises. Milk and egg are disliked; chickens are regarded as filthy and seldom eaten. A very acceptable beverage, called “passion” is prepared by roasting wheat grains over a charcoal fire until they assume a light brown color, after which they are pulverized, dissolved in water, and allowed to ferment before drinking.

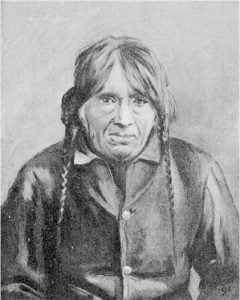

The Yuma local government resembles in some respects that of the ancient Aztecs. Their headmen are elected annually, but when the chief is a popular man his annual re-election is a mere matter of form, as in the case of Paschal, who was chief of the Yumas many years, and whose length of office terminated only with his death in 1887. Magill, who became chief at the dying request of Paschal, is now serving his third term, but annually a council of the most prominent men of the tribe is convened and the administration of the chief in office is either approved or condemned. To the chief is given both legislative and judicial authority. He settles all disputes and promulgates all laws; and when these laws seem treasonable they form the subject of learned discussion at a solemn gathering of tire people, and if they are not endorsed the chief must either revoke them or resign. To the subchiefs or captains of the Yuma rancherias is allowed the immediate supervision of their respective villages, and they are also advisers of the chief. To the sheriffs given the executions of all orders. He makes arrests, enforces sentences, and is held responsible for the prisoners after the arrest until the laws of the Yumas punish such offenses as murder, theft, and drunkenness swiftly and severely, usually by flogging. The culprit is stripped and fastened to a tree with his arms drawn high above his head, and the sheriff administers the castigation publicly. Although the whipping may be severe and delivered in the presence of a jeering crowd, the quivering individual endures the pain with a stoicism that is touching in its very muteness.

Chief of the Yumas, California, 1890

The Yumas are gradually increasing in numerical strength. The families average 3 or 4 children each. An official census taken in 1860 gave them 1,000 souls, while that of 1890 gave them 1,208 members, 659 males and 549 females. It is probable that the increase in, numbers is partially explained by the facility of immigration from neighboring tribes. Idiocy and physical deformities from birth are rare among these Indians, but unfortunately many are afflicted with hereditary ailments contracted through sexual indiscretions of the females. When Indians contract this loathsome disease their ignorance of its nature does not deter them from the fulfillment of the marital obligations, but does frequently result in stillbirth, or in the birth of a child with inherited syphilis, which may suffer for a few months or years and then die.

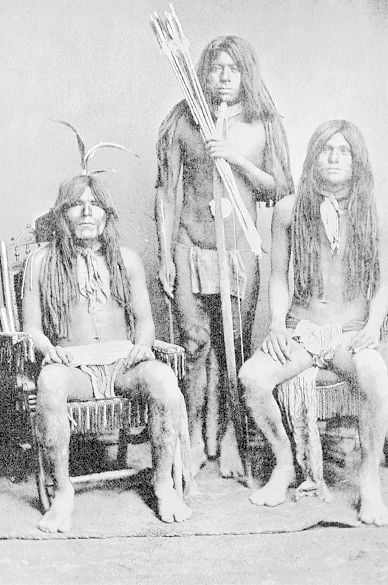

Physically the Yumas are generally magnificently proportioned. Their limbs are powerfully molded and their carriage is easy, straight, and erect. Their muscles are closely knitted, indicating latent power of endurance, and every movement evidences strength and agility. They are not handsome, but their bright eyes relieve their other uncompromising features of much stolidity. The women, when young, are generally plump and graceful, but with advancing years degenerate into cumbersome corpulency. As a rule, their teeth are beautiful and well preserved. The men do not permit beard to grow upon their faces, but prevent it by expilation. They are good workers and quick to learn, but lack ambition and knowledge. They do well when controlled and directed by some superior intelligence. They are rich when they have a few dollars, and will only work when it is gone. They are employed as deck hands on the steamers that run up the Colorado, and in the summer many find work in the hop fields and vineyards of Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties, California. In short, they work as laborers whenever they can find employment.

In May 1886, the old, abandoned military post opposite the town of Yuma was converted into a training school, admirably conducted under the auspices of the Catholic Church. The school has an attendance of 63 boys and 39 girls, a total of 109. They are taught the elementary common school branches, and in addition the boys receive instruction in carpentry, gardening, and the care of stock, while the girls are taught sewing, cooking, washing, ironing, and housekeeping. The government strives to inculcate habits of order, industry, and cleanliness, with practical experience of the advantages to be gained thereby. It is impossible to convert adult Yumas into civilized citizens. They will retain some of their customs from sheer force of habit, but the desired result is capable of accomplishment through a rising generation. It requires patience and time. Each succeeding generation will transmit more and more of the teachings of civilization to their immediate descendants.

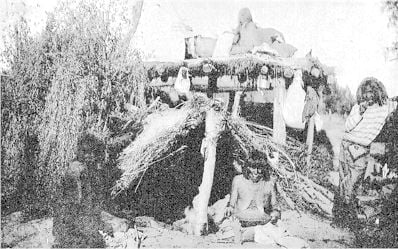

The Yumas are as clannish in their domestic arrangements as in their tribal relations. All the members of the family will have their crudely constructed houses built near together in one rancheria, and most of the families have both a winter and a summerhouse. The winter house is built by setting posts in the ground, inserting cross-pieces, and filling the roof and sides with intertwined willow twigs and sagebrush. Adobe mud is placed on top and on the sides, over the inner brush. The roof slopes to the rear. The front is left open, and generally faces the south, and the open space is usually closed by a tattered piece of cloth or blanket. The interior is subdivided into rooms according to fancy or the requirements of the family. The fire is built in the center of a room, and the whole house is filled with smoke, which gradually escapes through the interspaces in the sides and roof. The summerhouse, or “ramala”, is built to protect the family from the intense rays of the sun, and its construction is simple, being merely a brush shed. The ignored aged and infirm construct small conical huts of willow twigs by sticking the twigs into the ground and bringing them together at the top. These are usually covered with old gunny cloth and rags. A low triangular aperture is left open, through which the inmate must crawl. These rookeries are placed usually near to the patches of grain and vegetables.

The Yumas own some ponies and less cattle, but their fondness for curs is proverbial. They possess few arts and are compelled to purchase their few necessary wares and utensils. Pottery making is their chief industry, in which they use a reddish porous clay, obtained from the hillsides. Their pottery is remarkable for its perfect lines and graceful, uniform curves. Their wares, being porous, permit transudation, and are well adapted to the heated climate. Water in an “olla”, or water jug, will keep remarkably cool through the process of percolation and evaporation.

Handsome conical baskets, without handles, are manufactured from willow shoots deftly interwoven. Ropes and lariats are made of hides and of horsehair. Some of there hair reins, decorated with fancy-colored tassels, eau not bat excite admiration. They possess fairly good guns, but use the bow and arrow as weapons. The bows are made of willow, and have stout and strong strings made of animal sinews. Their arrows are reeds, with the shaft feather, tipped with triangular points of non or flinty stone and poisoned by being dipped into Putrid flesh. All of their wares are painted, usually in angular designs. They are fond of music, and manufacture 2 musical instruments, a flute, mud a rattle, the former made of reed, the latter simply a wild gourd, containing a few pebbles and4iaving a wooden handle. A jews’ harp is an Indian maiden’s delight, on which she will make a wild and most detestable noise.

The Yuma language is limited in vocabulary, slightly guttural, but soft and musical in sound, the meaning of a word depending largely upon its connection and accentuation, gestures giving the needed emphasis to conversation. The Yumas are said to be ignorant of writing, either by signs or hieroglyphics; but most of them speak Spanish more or less fluently and a few can speak fair English.

When girls arrive at the age of puberty it is customary to put them through a sweating process, which, it is claimed, prevents the occurrence of complications in giving birth to children. A curved hole, a little larger than the body it is intended to receive, about 2 or 3 feet deep, is dug in dry soil and heated by hurtling greasewood in it. The maiden then enters this oven, squats down, is covered over, and is given hot decoctions of indigenous plants. After perspiring freely she is taken out, led to the river, and receives a bath, after which she is considered, marriageable, and is consigned to the care of some elderly relation, who is held responsible for her purity. When a young man is attracted by a maiden he first seeks the consent of the father, who apparently refuses, but as soon as practicable thereafter, when the young man is certain of the parent’s absence, he gaudily decorates himself, visits the girl, and pops the question in the regulation fashion. A modest expression of face and no reply is received by the lover as an affirmative. If the maiden refuses, her language is so emphatic that it deters further advances.

Polygamy does not exist among the Yumas. Sexual indiscretions are not punished, as formerly, by whipping. The husband, actuated by pride, never interposes obstacles to his wife’s desires. Divorces are easily obtained, and do not affect the social standing. If a woman is led astray by a man of another tribe or race she is considered disgraced and virtually becomes an outcast.

Childbirth among the Yuma women is a natural and speedy process, the mother returning to her usual work a few hours after the occurrence, as if nothing unusual had happened. The birth of a boy affords special pleasure to the father and daughter is accepted with stoicism. The children are not named until they can talk; then some chance saying by them, comical or unusual, determines the future name. The child lives nearly a year in its papoose case, made of board covered with bark and decorated to suit individual fancy, some of the cases being very handsome.

The Yumas cremate their dead. When a Yuma dies his friends build a very substantial pile of brush and dry wood, place the body wrapped in a blanket or a piece of canvas on top of the pile, and ignite it, while those gathered about the funeral pyre howl dismally and apparently with certain satisfaction over the death of the one who has passed to the “happy hunting ground”. Each relative of the deceased cuts off a small piece of his own hair and throws it upon the burning body. When misfortune comes upon a family it is attributed to deliberate witchcraft perpetrated by some enemy, and if an individual is seriously accused of witchcraft his prospects of a sudden death are uncomfortably certain.

The medicine Men, who claim appointment from the Great Spirit and officiate also as priests, are aged men, possessing much low cunning and shrewdness. Their curing methods consist chiefly in sucking, slapping, or blowing: upon the supposed diseased part of the patient’s body. If the medicine man makes 3 false prognoses in a family, or 9 in a tribe, a relative demands an explanation, and if it is not satisfactory the medicine man is simply murdered with a mesquite club and no investigation is made by the tribe. With this alternative facing him, it may be possible that sometimes the practitioner makes the result correspond with the prognosis, in order that the beauties of prophesy may harmonize with accuracy. Their power and influence are gradually diminishing.

The Yumas usually dress as little as the sun will permit, though some wear well-made and clean clothing. The women glory in dresses of bright colored and figured calico. Until within the last few years the men bestowed, very little attention to clothing, their wardrobe, often being limited to gay-colored “gee-strings”, At present nearly, all of time men wear clothes approaching civilized ideas of dress, though some ludicrous combinations are often seen, such as a cast-off beaver and a breech cloth, or a pair of pantaloons, or a shirt only Bead necklaces and wristlets are popular. The men wear their hair long, frequently plastering it with greasy, reddish clay, which tends to destroy the vermin, and both men and women tattoo their faces with charcoal or clay.

The Yumas observe their annual feasts. Of these the most interesting are the mourning feasts, devoted to lamentations for the loss of friends and relatives during the year, to which invitations are frequently, issued to neighboring tribes. This feast may be delayed, but is never forgotten nor neglected.

Citations:

- The statements giving tribes, areas, and laws for agencies are from the Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1890, pages 484-445, The population is the result of the census.[

]