The teepee, a versatile and historically significant structure, has been widely associated with the Lakota Sioux in popular culture, particularly through depictions in Hollywood Westerns. However, the use of conical dwellings like the teepee extends beyond the Plains tribes to other indigenous peoples across North America, as well as to groups in northern Scandinavia and Siberia. This article explores the origins, construction, and cultural significance of the teepee, with a particular focus on its architectural features and adaptations to various environments. It also addresses misconceptions about indigenous housing styles, highlighting the diverse ways in which Native American tribes built their homes, depending on their resources and needs.

Hollywood has taught us much during the 100+ years of making Westerns. Everyone now knows that the Lakota (Sioux) invented the teepee, and that all teepees are made of buffalo hides. By the time that the White Man arrived, the Sioux invention had spread throughout the continent. Those Indians, who didn’t have teepees or ride horses all the time, were too poor to even own a teepee, so they had no homes at all.

Did you ever notice that until the filming of the beautiful movie, “The New World,” there were very, very few movies which portrayed non-Plains Indians and showed them inside their houses? This criticism about the portrayal of indigenous housing styles even applies to another beautiful movie, “The Last of the Mohicans.” It will indeed be a sign that the Age of Aquarius has dawned, when Hollywood decides to accurately portray the cultures of the Southwest and Southeast that built apartment buildings, which could hold several hundred people.

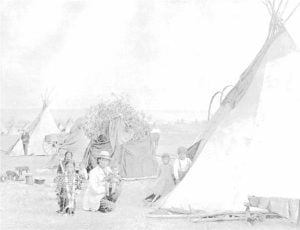

Assiniboine Sioux and Gross Ventre Home Life, Tepees covered with Cloth

The teepee is common structure among many indigenous peoples of the northern hemisphere, in particular, the higher latitudes. It was especially common in Siberia, northern Scandinavia and much of North America. Teepees have probably been built for thousands of years by the Sammi (Lapps) of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia, where an abundance of domesticated reindeer hides made possible the use of animal skins for shelter. Sammi families live in them to this day during reindeer herding season or on fishing/hunting expeditions. Of course, nowadays, there might be a Volvo SUV parked beside the Sammi teepee!

The structural principals behind a teepee are simple, yet they create a lightweight structure, which is highly resistant to wind pressure in all directions, and when adequately insulated, can keep the occupants comfortable in the coldest of winter weather. The use of saplings and poles for the main structure instead of the heavy posts required in earth lodge construction, reduced the time and energy required to cut the trees with stone axes.

Wooden poles are set into the ground in a circular or oval pattern. The poles are leaned against each other and then securely tied at the top. Wind pressure from one side is transferred by the structural form into the ground on the opposite side. Because of the conical shape, wind pressure is highest next to the ground and least at the top. The conical shape also creates an upward air circulation, which cools the interior in the summer and draws smoke out in the winter. Interior baffles and flaps are suspended above head height in the winter to hold warm air in, while moisture from the breaths of humans inside escapes with the smoke.

How about the Sioux?

At the time which European settlers were first arriving in the Americas, the ancestors of the Dakota, Lakota and Nakota Sioux were living in the Upper Midwestern United States and western Ontario Province. The Santee Sioux still live in Minnesota. There were many Sioux tribes and agricultural towns in Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina. The original Sioux population there was probably much larger there than among the northern bands. Both the northern and southern branches of the Sioux once lived in round structures with conical roofs. The floors of these houses were often recessed below ground about 12-24 inches. Undoubtedly, all the Sioux hunted the Eastern Woodland bison, and the Northern Sioux sent out bands of hunters into the Dakotas to harvest Western Plains bison.

Once bands of Northern Sioux began moving permanently into the grassy plains of the Dakotas and Alberta, however, they had to adapt to limited wood resources. It is quite likely that their original prairie houses looked something like small Mandan earth lodges. (See article on Mandan earth lodges.) Sod replaced bark shingles as the roofing material. The Sioux hunted whatever game was available near their homes. However, once the Sioux and other Plains tribes, such as the Cheyenne, obtained horses, they learned that by following the annual migrations of the great bison herds, there would be a plentiful supply of meat and hides for the whole year. There was then a need for a form of housing, which was mobile.

As seen in the photos below, the teepee had an ancient tradition in the Great Lakes Basin. However, the skins of such large animals as elk, Eastern Woodland bison and bears were too valuable as raw materials for shoes and winter clothing to be extensively used for housing. The Northern Woodland tribes did not know how to weave cloth, so that was not an option for covering tents and teepees. However, once on the Great Plains and mounted on horses, the Native peoples suddenly had an abundances of bison skins. Also, one of the more plentiful tree species was the Lodge pole pine. Its trunks were straight and relatively thin — perfect for making lightweight teepee poles.

The primary innovation of the Plains tribes was to learn how to cure and sew together sufficiently large sheets of bison leather in order to cover a teepee frame. When it was time for a band to break camp, the leather sheets were folded and placed upon travois — simple triangular pole frames pulled by horses. The combination of an abundance of bison, horses and the mobile, bison hide-sheaved teepee created the relatively short-lived Great Plains Culture that has been so romanticized by the movie industry. Many Sioux bands forgot completely their former agricultural skills in the Great Lakes Basin and became full time hunters. They traded skins and smoked meat with other tribes to obtain whatever agricultural commodities they needed. Military societies developed among the bands because of the need to protect enormous tracts of bison hunting territory from the hunters of competing tribes.

Illustrations of Teepees with Description

The Adena Culture — The ethnic identity of the Adena Culture People is unknown, but they probably migrated up the Mississippi River Basin into the Ohio River Basin between around 1000 BC – 800 BC. Little remains of their houses other than fire-hardened hearths because their homes consisted of teepees sheaved with thin saplings and reeds. (See article on the Adena Mounds.) (VR Image by Richard Thornton, Architect)

Ottawa teepee, sheaved with reeds — This photo was made in southern Ontario in the 1860s. It shows that even at that late date, some Ottawa villages were building teepees identical to those of the Adena Culture 2500 years earlier. The Ottawa, Ojibwe and Potawatomi were sister tribes with similar customs, that had been one tribe in earlier times. The Ottawa were concentrated north of Lake Ontario when the French arrived in Canada. Individual bands of these Great Lakes peoples adapted to local environmental conditions by building variations of the teepee concept for their winter housing. They lived in wigwams during the warmer months. (Photo courtesy of the Architectural Society of Ontario)

Ojibwe teepee, sheaved with birch bark — The Ojibwe (Chippewa) were concentrated in southwestern Ontario and the Lake Michigan Basin when first contacted by Europeans. There is an abundance of White Birch trees in this region, whose bark made ideal materials for sheaving houses and building canoes. Note that this teepee is framed by staking two semicircles of saplings and then joining them together at the top with a ridge pole. (Photo courtesy of the Architectural Society of Ontario)

Potawatomi teepee, sheaved with deer and elk shingles — The many bands of the Potawatomi were living in southwestern Ontario, Michigan, Wisconsin and the future locations of Milwaukee, Detroit and Chicago when European explorers first made contact with them. (See the five article mini-series on the Potawatomi.) During the warm months they either lived in wigwams or in basket-like houses woven from cattail stalks. (See articles on Wigwams and Basket Houses.) During the winter months they migrated up into the forested hill country and lived in teepees. Although the upcountry provided more game, the temperatures were bitterly cold. Their teepees were double or triple lined. Relatively thin deer skins were attached to the inner surfaces of the poles. Thicker elk and buck skin shingles were lashed to the outside of the poles. Often the Potawatomi also stacked saplings and reeds around the hide shingles so that there would be an air gap between a layer of frozen snow and the hides. (Photo courtesy of the Architectural Society of Ontario)

Shoshone teepees, sheaved with bison hides — This is a photograph of the band led by the famous Shoshone chief, Washakie. The Mormon settlers of Utah practiced a very enlightened policy in their relations with Native Americans. This often resulted in peaceful relations with nearby tribes, but not always. A particularly friendly and mutually beneficial relationship existed between the colony’s leaders in Salt Lake City and the Shoshone band led by Washakie. The Shoshone built medium sized, unadorned teepees out of bison hides. However, their teepees did have wind flaps and interior baffles to control air flow and smoke from small fires used for heating in the winter. (Photo courtesy of the Washakie Historical Society)

Assiniboine teepee sheaved with bison hides and with painted motifs — This photo was probably made in the 1890s or very early 1900s. Some Plains Indian tribes painted designs on the walls of their teepees. It is likely that this practice was only common when there was peace and prosperity. There would be little time for esthetic activities if an enemy tribe or the cavalry were roaming the nearby countryside. The designs represented clans, bands or achievements of one of the teepee’s occupants. (Photo courtesy of the FirstNations.us web site)