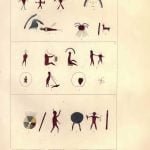

Nundobunewin, or War. The devices used to commemorate the incidents of war, among the northern tribes, will now be brought forward. Most of these are employed to excite the memory in the recital of songs preparatory to the setting out of war parties. It will be seen by the annexed figures, that these devices are chiefly of the ke-ke-no-win, or highest grade of the symbolic.

The figures from 1 to 4, Plate 56 C, comprise what is deemed a continuous song, and although each stanza of it may be sung by a separate individual, the general theme is preserved. Figure 1 represents the sun, which is to be regarded in this connection as not only the source of light and knowledge to men, but a symbol of vigilance. The warrior merely sings I am rising. In figure 2 he assumes to possess this power himself, and by one hand pointing to the earth, and another extended to the sky, declares his wide-spreading power and fearful prowess. He sings, I take the sky I take the earth. In number 3 he appears under the symbol of the moon, denoting the night to be the season of secrecy and warlike enterprise. With a proud feeling of exaltation, he sings I walk through the sky. In figure 4 he personifies Venus, here called the Eastern Woman, or the Evening Star, who is thus appealed to, as a witness of his valor and warlike cunning. He sings, The Eastern Woman calls. The entire song as thus expressed, in the native dialect, is this:

First War Song

- Tshe be moak sa aun.

- Ma mo yah na geezhig Ma mo yah, na ahkee Mo mo yah na.

- Bai mo sa yah na, geezhigong Bai mo sa yah na.

- Wa bun ong tuz-ze kwai Ne wau ween, ne go ho ga.

Divested, in some degree, of its symbolic shape, the verses may be read thus:

- I am rising to seek the warpath.

- The earth and the sky are before me.

- I walk by day and by night.

- And the evening star is my guide.

In the ensuing six figures, (A, Plate 56) a like unity of theme is preserved. Figure 1 personifies an active and swift-footed warrior; he is therefore depicted with wings. He sings, I wish to have the body of the swiftest bird. In No. 2 he is re presented as standing under the morning star, which, as a sentinel, is set to watch, or should terminate his nocturnal enterprise. He sings, Every day I look at you; the half of the day I sing my song. In No. 3, he is depicted as standing under the centre of the sky, with his war club and rattle. He sings, I throw away my body. In figure 4, the eagle, a symbol of carnage, is represented as performing the circuit of the sky. He sings, The birds take a flight in the air. In figure 5, he imagines himself to be slain on the field of battle. He sings, Full happy am I to be numbered with the slain. And in figure 6, he consoles himself with the idea of posthumous fame, under the symbol of a spirit in the sky. He sings, The spirits on high repeat my name.

Second War Song

- I wish for the speed of a bird, to pounce on the enemy.

- I look to the morning star to guide my steps.

- I devote my body to battle.

- I take courage from the flight of eagles.

- I am willing to be numbered with the slain.

- For even then my name shall be repeated with praise.

It is not deemed necessary to encumber these pages with the native words, which are before me, nor with any farther attempt to disencumber them from their symbolic meanings. The system adopted in the preceding song will apply to this, and to all others, which shall be selected with similar care and symbolic propriety in the arrangement. By this method, these songs, which have been usually exhibited as meager and disjointed portions of rhapsodies, are shown to have a consistency and import which may well be supposed to inspire the singer with martial warmth, and prepare his mind for deeds of daring. The symbolic pictures form, indeed, the true key to the nug-a-moon-un, or songs, and show to what extent the mnemonic symbols are applied.

Sageawin, or Love

As a proper appendage to this part of the inquiry, I subjoin the seven following mnemonic symbols of love. (B, Plate 56) The subject is one which will scarcely bear to be treated of at much length, for which, indeed, but little space can be assigned, and yet, without some allusion to it, there would be manifestly a branch of the inquiry, and not an unimportant one, wanting. And here also, as in war, in the meda, and in the symbols of hunting, the theme is to be regarded as unbroken.

Love Song.

Figure 1 represents a person who affects to be invested with a magic power to charm the other sex, which makes him regard himself as a monedo, or god. He depicts himself as such, and therefore sings It is my painting that makes me a god. In No. 2, he further illustrates this idea by his power in music. He is depicted as beating a magic drum. He sings Hear the sounds of my voice, of my song; it is my voice. In No. 3, he denotes the effects of his necromancy. He surrounds himself with a secret lodge. He sings I cover myself in sitting down by her. In No. 4, ho depicts the intimate union of their affections, by joining two bodies with one continuous arm. He sings I can make her blush, because I hear all she says of me-. In No. 5, he represents her on an island. He sings Were she on a distant island, I could make her swim over. In No. 6, she is depicted asleep. He boasts of his magical powers, which are capable of reaching her heart. He sings Though she was far off, even on the other hemisphere. Figure 7 depicts a naked heart. He sings I speak to your heart. Still further divested of their symbolic dress, and relieved of some points of peculiarity, the entire nugamoon may be thus read:

- It is my form and person that makes me great.

- Hear the voice of my song it is my voice.

- I shield myself with secret coverings.

- All your thoughts are known to me blush!

- I could draw you hence, were you on a distant island;

- Though you were on the other hemisphere.

- I speak to your naked heart.

That the system of mnemonic symbols may be clearly understood, and the kind of aid which it imparts to the memory appreciated, it is applied, in the following example, to the eight verses of the latter part of the 30th of Proverbs, from the 25th to the 32d inclusive. The English version of these, being in every one’s hand, need not be quoted. The following is their translation in that now rare and extraordinary effort of literary-mission labor, Eliot’s Bible in the Massachusetts language.

Verse 25. Annunekqsog missinnaog matta manuhkesegig, qut onch quaquoshwe-tamwog ummeetsuong au oo nepunae.

26. Ogkoshquog nananoochumwesuog, qut onch weekitteaog qussukquanehta.

27. Chansompsog wanne ukeihtassootamooeog, qut onch sohhamwog nag wame moeu chipwushaog.

28. Mamunappeht anunuhqueohts wunnutchegash, kah appu tahsootamukkom-ukqut.

29. Nishwinash nish wariumaushomoougish nux yauunash tapeunkgshaumooash.

30. Quonuonu noh anue menuhkesit kenugke puppinashimwut, kah matta qush-kehtauoou howausinne.

31. Quohgunonu, nomposhimwe goats wonk, kah ketasioot, noh wanue kowan ayeuuhkone waabehtauunk.

32. Mattammagwe usseas, tah shinadtkuhhog, asah matanatamas, ponish kenutcheg kuttoonut.

The symbolic figures represented in A, Plate 47, may be put to denote the import of the principal object of each verse, the symbol being taken as the key.

Number 25. An ant.

Number 26. A coney.

Number 27. A locust.

Number 28. A spider.

Number 29. A river a symbol of motion.

Number 30. A lion.

Number 31. A greyhound. 2. A he-goat. 3. A king.

Number 32. A man foolishly lifting up himself to take hold of the heavens.

It must be quite evident that while this primitive mode of notation is wholly inadequate to the purpose of recording sounds, any farther than the mere names of the objects prefigured by the key-picture, yet, the words themselves having been previously committed to memory, these key-pictures are a strong aid and stimulant to the memory. This is precisely the scope and object of the Indian bark pictographs and ” music boards,” and other modes of drawings intended to denote songs or chants. And where many such are to be sung, as is the case with the Medas and singers in their public ceremonies, the songs being generally short, it may be conceived to be a system of much utility to them. It is, at once, their book and musical scale.