In this third paper on the ethnology of the Blackfoot Indians full recognition should again be given Mr. D. C. Duvall, with whose assistance the data were collected by the writer on a Museum expedition in 1906. Later, Mr. Duvall read the descriptive parts of the manuscript to well-informed Indians, recording their corrections and comments, the substance of which was incorporated in the final revision. Most of the data come from the Piegan division in Montana. For supplementary accounts of social customs the works of Henry 1 , Maximilian 2 , Grinnell 3 , Maclean 4 , and McClintock 5 are especially worthy of consideration.

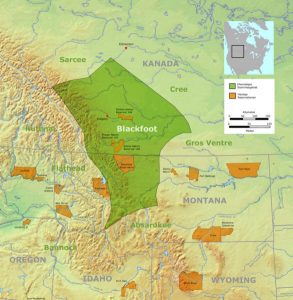

Since Social Life of the Blackfoot Indians is an integral part of an ethnographic survey in the Missouri-Saskatchewan area some general statements seem permissible for there is even yet a deep interest in the order of social grouping in different parts of the world and its assumed relation with exogamy, to the current discussion of which our presentation of the Blackfoot band system may perhaps contribute. We believe the facts indicate these bands to be social groups, or units, frequently formed and even now taking shape by division, segregation and union, in the main a physical grouping of individuals in adjustment to sociological and economic conditions. The readiness with which a Blackfoot changes his band and the unstable character of the band name and above all the band’s obvious function as a social and political unit, make it appear that its somewhat uncertain exogamous character is a mere coincidence. A satisfactory comparative view of social organization in this area must await the accumulation of more detailed information than is now available. A brief resume may, however, serve to define some of the problems. Dr. Lowie’s investigation of the Assiniboine reveals band characteristics similar to those of the Blackfoot in so far as his informants gave evidence of no precise conscious relation between band affiliation and restrictions to marriage. The Gros Ventre, according to Kroeber, are composed of bands in which descent is paternal and marriage forbidden within the bands of one’s father and mother, which has the appearance of a mere blood restriction. The Arapaho bands, on the other hand, were merely divisions in which membership was inherited but did not affect marriage in any way. The Crow, however, have not only exogamous bands but phratries. The Teton-Dakota so far as our own information goes, are like the Assiniboine. For the Western Cree we lack definite information but such as we have indicates a simple family group and blood restrictions to marriage. The following statement by Henry may be noted: ” A Cree often finds difficulty in tracing out his grandfather, as they do not possess totems – that ready expedient among the Saulteurs. They have a certain way of distinguishing their families and tribes, but it is not nearly so accurate as that of the Saulteurs, and the second or third generation back seems often lost in oblivion.” On the west, the Nez Perce seem innocent of anything like clans or gentes. The Northern Shoshone seem not to have the formal bands of the Blackfoot and other tribes but to have recognized simple family groups. The clan-like organizations of the Ojibway, Winnebago and some other Siouan groups and also the Caddoan groups on the eastern and southern borders of our area serve to sharpen the differentiation.

Social Life of the Blackfoot Indians

- Blackfoot Amusements and Games

- Blackfoot Bands

- Blackfoot Birth Customs

- Blackfoot Care and Training of Children

- Blackfoot Courtship

- Blackfoot Death And Mourning

- Blackfoot Division of Labor

- Blackfoot Divorce

- Blackfoot Etiquette

- Blackfoot Family Relationship Terms

- Blackfoot Gambling

- Blackfoot Heraldry And Picture Writing

- Blackfoot Marriage and Its Obligations

- Blackfoot Names

- Blackfoot Oaths

- Blackfoot Property Rights

- Blackfoot Tales Of Adventure

- Blackfoot Tribal Divisions

- Blackfoot Tribal Organization and Control

- The Blackfoot Mother-in-Law Taboo

- The Way Blackfoot Reckon Time

Introduction to Social Life of the Blackfoot Indians

The names of Blackfoot bands are not animal terms but characterizations in no wise different from tribal names. Those of the Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Teton-Dakota are, so far as reported, essentially of the same class. It seems then that the name system for these bands is the same among these neighboring tribes of the area and that it is an integral part of the whole system of nomenclature for groups of individuals. This may be of no particular significance, yet it is difficult to see in it the earmarks of a broken-down clan organization; it looks for all the world like an economic or physical grouping of a growing population.

We have seen in the Blackfoot system the suggestion that the band circle or camp circle organization is in function a political and ceremonial adjunct and that the exogamous aspects of these bands were accidental. So far as we know this holds to a degree for other tribes using the band circle.

It seems probable that many discussions of social phenomena could be expedited if clear distinctions were established between what is conventional and what is the result of specific functions and adaptations. Unfortunately, our ignorance of the processes involved and their seeming illusiveness of apprehension make such a result well-nigh hopeless. By the large, conventional things, or customs, appear to be products of ideation or thinking. Now a band circle is clearly a scheme, a conception, that may well have originated within the mental activities of a single individual, a true psychic accident. Indeed this is precisely what conventions seem to be customs, procedures or orders that happen to become fixed. A band, on the other hand, is not so easily disposed of. The name itself implies some-thing instinctive or physical, as a flock, a grove, etc. Something like this is seen in the ethnic grouping of the Dakota since we have the main group composed of two large divisions in one of which is the Teton, this again sub-divided among which we find the Ogalalla, and this in turn divided into camps, etc. Though detected by conventionalities of language this dividing and diffusing is largely physical, or at least an organic adjustment to environment. Then among the Ojibway we have a population widely scattered in physical groups but over and above all, seemingly independent, a clan system; the latter is certainly conventional, but the former, not. Now the Blackfoot band seems in genesis very much of a combined instinctive and physical grouping, in so far as it is largely a sexual group and adapted to economic conditions. In its relation to the band system of government and its exogamous tendency it is clearly conventional. What may be termed the conventional band system consists in a scheme for the tribal group designated as a band circle. This scheme once in force would perpetuate the band names and distinctions in the face of re-groupings for physical and economic reasons. Something like this has been reported for the Cheyenne who have practically the same band scheme but live in camps or physical groups not coincident with the band grouping, hence, their band was predominating conventional. The following statement of the Arapaho, if we read correctly, is in line with this: “When the bands were separate, the people in each camped promiscuously and without order. When the whole tribe was together, it camped in a circle that had an opening to the east. The members of each band then camped in one place in a circle.” All this in turn seems to support the interpretation that the band circle system is merely a conventionalized scheme of tribal government. We have noted that among the Blackfoot the tribal governments are so associated with the band circles that they exist only potentially until the camps are formed; at other times each band is a law unto itself. So far as our data go something like this holds in part at least, for the neighboring tribes. As a hypothesis, then, for further consideration we may state that the band circles and the bands are the objective forms of a type of tribal government almost peculiar to this area, an organization of units not to be confused with the more social clans and gentes of other tribes to which they bear a superficial resemblance. In closing, we may remark that exogamy is often but a rule for marriage respecting some conventional groupings. The Blackfoot appear to have paused at the very threshold of such a ruling for their bands.

Citations:

- Henry and Thompson. New Light on the Early History of the Great Northwest. Edited by Elliott Coues. New York, 1897.[↩]

- Maximilian, Prince of Wied. Early Western Travels, 1748-1846. Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites. Cleveland, 1906.[↩]

- Maclean, John. The Gesture Language of the Blackfeet. (Transactions, Canadian Institute, Vol. 5. Toronto, 1898); Maclean, John. Canadian Savage Folk. The Native Tribes of Canada. Toronto, 1896; Maclean, John. Social Organization of the Blackfoot Indians. (Transactions, Canadian Institute, Vol. 4, 1892-93. Toronto, 1895); Maclean, John. Blackfoot Amusements. (Scientific American Supplement, June 8, 1901, pp. 21276-7).[↩]

- Grinnell, George Bird. Blackfoot Lodge Tales. New York, 1904.[↩]

- McClintock, Walter. The Old North Trail. London, 1910.[↩]

Discover more from Access Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.