Playing for stakes was always a favorite and the games to be described here were rarely played except in gambling. Gambling is often spoken of as fighting, or war, and in turn war is spoken of as gambling. This is reflected in a myth where the players’ scalps were at stake. 1

The Hand-Game

Piaks kaiosin, approximately fancy gambling, was in a way team work, sometimes as many as twenty-five men on a side, band playing against band or even camp against camp. The outfit consists of 4 hiding sticks, or two pairs, 12 counters and a number of drumsticks for beating time on lodge poles set up in front of the players. The pair of hiding sticks are designated as the short and the long, though they are really of equal length, the one called long being designated by a string wrapped about its middle. They are about the thickness of an ordinary lead pencil and about 7 cm. in length. The materials are wood or bone. The counters are about 38 cm. long, of plain wood sharpened at one end for sticking up in front of the players. The drumsticks are short clubs of no definite form. Each side takes a pair of hiding sticks and selects a man to do the hiding and one to do the guessing, according to their known skill. Each hiding man, or leader, faces the guesser of the opposing side and the play begins. The leaders put their hands behind them and then show their hands when the guess is made. The side guessing correctly takes one counter and also their opponents’ pair of hiding sticks. This opens the game. There are now two leaders for the playing side. They confront the guessers of their opponents. The player’s side now sings and drums upon the tipi poles, provided for that purpose, apparently to divert the attention of the guessers. For every failure of a guesser, the playing side takes a counting stick. Should one of the leaders be guessed correctly, he gives his hiding stick to his companion who plays with the four. If the guess is now wrong, he takes one counter and restores a pair to his companion to play as before. However, should the guess be correct, the playing side loses the hiding sticks to their opponents. Thus the play continues until one side has the 12 counting sticks, or wins. 2

The songs have a definite rhythmic air but consist of nonsense syllables. However, jibes and taunts are usually improvised to disconcert the guessers. The game is very boisterous and, in a way social, but is never played except for stakes of value, as horses, robes, guns, etc.

Formerly, this game was often played by members of the All-Comrades Societies, as the Braves against the Dogs, etc. In such cases the songs were from their own rituals. The man handling the sticks was sometimes very skilful in deceiving the guessers. To disconcert him, the opposing side often counted coup on him. One would recount how he took a scalp, leap upon the shoulder of the player, grasp his hair, flash a knife, etc., he all the while handling the sticks. They might pretend to capture his blanket or repeat any other deeds they had done in war. The idea was that if the deed counts were true, the re-counting of them would give power to over-come the skill of the player. This made the game noisy and rough, but quite exciting. The players were always skilful jugglers and regarded as medicine men. The amount of property changing hands in such gambling was truly astonishing, whole bands and societies sometimes being reduced to absolute poverty and nakedness. Women may play the game but with three counting sticks instead of twelve.

The Wheel Gambling

For this game, a small wheel about 7 cm. in diameter is used. The form is precisely like that of the Gros Ventre shown in Fig. 22, p. 188, Vol. I, of this series. There are two sets in the Blackfoot collection one of which has six spokes, the other seven. The spokes are distinguished by beads of different colors or combinations. For the game a wheel and two arrows are required, there being but two players. The arrows in the collection have metal points and are feathered. They are about 85 cm. long. In playing the wheel is rolled by one of the players toward an obstruction, usually a board, about 6 m. distant. The two follow it closely and as it falls after striking the obstruction, try to thrust their arrows under it. This must be done so that the wheel will fall upon them, not cause its fall. The count is according to the position of the spokes upon the arrows. The winner rolls the wheel, the advantage being always with the one who does this. The counts are usually in multiples, of five, values being assigned to the various spokes by mutual agreement at the opening of the game. 3 Small pebbles are used as counters, or chips. The betting is by pledging a blanket for so many pebbles, a knife for so many, etc.

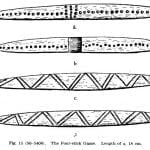

The Four-stick Game

To the Blackfoot this is known as “travois gambling,” and is played by women. A set in the collection was said to be of buffalo bone (Fig. 15). The sticks were named six, two, and snakes; though sometimes designated as twos and snakes, a pair of each. The detail of the markings varied but followed the same general scheme in so far that the snakes were always marked with the wave-like design. They were cast upon the ground or a blanket. Since the opposite sides of the sticks are blank there are eight faces. The usual count is as follows: zero two blanks, one snake and a or b; 2, two blanks and two snakes; 4, four blanks; or as they appear in the figure; 6, three blanks and six (b), or one blank, two snakes and two (a); one blank, six (b) and two snakes counts nothing but the player may pick up the stick called six and throw it upon the others to turn them, counting according to the result. Other combinations give no score. The player continues to throw so long as the above combinations result; failing, the turn passes to the next. As a rule, there are but two in the game. 4 The number of points in a game and the wagers are a matter of agreement between the players. 5

Certain games well known to neighboring tribes were not recognized by our informants as having been played by the Blackfoot. Among these were the plum stone, or button dice, the moccasin game, the hoop game, the 102 stick game, the cup-and-ball, the snow snake, ice-gliders, and winged bones. Most of them had been seen, but in the hands of aliens. Odd-and -even seems to have been known to the Northern Blackfoot, but was not in favor. 6 We have found no traces of ceremonial associations with these games. While mention of the wheel games is made in several myths, this seems purely circumstantial, except that the Twin-brothers are credited with originating the netted wheel. 7

The small spoked wheel of the Blackfoot is practically identical with that of the Gros Ventre. According to Culin, this beaded type has been observed among the Crow, Nez Perce, Thompson and Shushwap tribes, suggesting its origin, if not with the Blackfoot, at least, with some of their neighbors. The particular form of button used in the Blackfoot hand-game seems to-belong to the west of the Rocky Mountains, to the coast and southward in the plateaus. The beating upon a pole is found among the Nez Perce, Kootenai and perhaps elsewhere. While the Gros Ventre had the Black-foot names “long and short,” their buttons and method of play were more like those of the Arapaho. The stick dice (travois game) when rigidly com-pared as to form and marking, bear close parallels among the Gros Ventre. Hidatsa, and Chippeywan with less correspondence west of the Rockies. On the other hand, the Blackfoot indifference to seed and button dice-tends to class them with western tribes. Neither the Blackfoot nor the Gros Ventre seem to have used the large hoop and double darts of the Dakota, Omaha, and Arapaho. Thus, in a general way, the Blackfoot fall into an ill-defined group comprising tribes on the head-waters of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers. They seem on the whole, to incline more toward the Plateau and Shoshone area than to the Siouan or Algonkin. Of greater interest, perhaps, is our failure to find any game associated with the stalking of buffalo or any other ceremony. So far as we can see, all games are to the Blackfoot either amusement or gambling and a resume of our account will show that many of the former also reflect the gambling conception.

Citations:

- Vol. 2, p. 132.[↩]

- For other brief accounts for the Blackfoot see Grinnell, George Bird. Blackfoot Lodge Tales. New York, 1904, p. 184; Maclean, John. Canadian Savage Folk. The Native Tribes of Canada. Toronto, 1896, p. 56.[↩]

- See Grinnell, George Bird. Blackfoot Lodge Tales. New York, 1904, p. 183; Maclean, John. Canadian Savage Folk. The Native Tribes of Canada. Toronto, 1896, p. 55, Maclean, John. Blackfoot Amusements. (Scientific American Supplement, June 8, 1901, pp. 21276-7); Culin, Stewart. Games of the North American Indians. (Twenty-fourth Annual Report, Bureau of American Ethnology, Washington, 1907), p. 448.[↩]

- Culin, Stewart. Games of the North American Indians. (Twenty-fourth Annual Report, Bureau of American Ethnology, Washington, 1907), p. 56-57.[↩]

- The section on games is entirely based upon information gathered by D. C. Duvall, chiefly among the Piegan, supplemented by data from the other divisions.[↩]

- Maximilian, Prince of Wied. Early Western Travels, 1748-1846. Edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites. Cleveland, 1906, p. 254.[↩]

- See Vol. I of this series, 24, 42, 60, 64, 132.[↩]