We now come to what is perhaps the most interesting topic in the material life of the southern tribes, the woven feather technique. An art so ancient and so elaborate can hardly be expected to have persisted from colonial times down to the present day where the process of deculturation among the conquered tribes has gone so far. But surprising as it is, the Virginia Indians have not entirely forgotten, nor even lost, the art of weaving feathers into the foundation of textile fabrics. The antiquity of the woven-feather technique is attested by virtually all the authors of the old colonial descriptions of Indian life, while its beauty and high esthetic quality have made it the supreme textile achievement in a number of ethnic centers on the Pacific coast, in California, Mexico, and Ecuador, as well as in Polynesia. In the Gulf area the feather technique was also widely distributed. Fortunately we have a number of references to it and some details of description are recorded. After presenting the Pamunkey facts, I shall revert to the distribution of this art in the Southeast and upward along the Atlantic coast to southern New England, giving reasons for the inference that this admirable art was one of the complexes emanating from some center of dispersion in the south and drifting north along the coast.

The feather art is reported in early times from most of the lower Mississippi and Gulf tribes and as far north as the Delawares of Pennsylvania and the Narragansett of Rhode Island.

The facts pertaining to the Virginia survival of this much discussed art and technique are as follows:

In 1919 I learned at the Mattaponi village from Mrs. John Langston that in her mother’s time knitted textiles were occasionally made with wild-turkey feathers inserted at the loops, covering the whole of one side of the fabric. She also recalled the use of feathers other than those of the turkey in the making of decorated moccasin tops and bags. Particular mention was made of capes so covered with turkey feathers as to be warm and durable as well as beautiful. Mrs. Langston claimed to have been taught the process by her mother and then referred to several other old women who should have seen the feather articles in their younger days, and who perhaps knew also how to knit them. As a result of stimulating her interest she undertook then to make a specimen or two.

From Margaret Adams, however, the oldest woman at Pamunkey town, who herself came from Mattaponi originally; the best specimens of the work were procured. Upon these specimens and information gleaned at large from the older women of both bands we may base the claims of the survival until today of the feather technique in Virginia. The specimens submitted are indeed poor but tangible evidences of the old art’s provenience and partial character.

The material employed in the technique is native raised and homespun cotton, which forms the base material of the fabric.

The feathers used are primarily those of the wild turkey, domestic turkey, shelldrake, Guinea fowl, Virginia cardinal, flicker, and in one case parts of commercial ostrich-feathers dyed blue.

The technique itself is not complicated, being neither particularly difficult to operate nor to describe. The plain knitting stitch is employed. Four steel or bone needles are used. Mrs. Adams said that she understood that the long leg bones of herons, “cranes,” were used before trade needles reached them. Several of these (fig. 130) were obtained as specimens of the same, taken from the great blue heron. As the knitting proceeds, at a third or fourth stitch, a single feather is worked into the fabric, being caught fast by its base and some-times the shank of the plume, which is, of course, soft and pliable, the feathers being carefully selected with this in view, and is caught in several stitches to hold it tight. In the better executed specimens the feathers are quite firmly attached. The turkey feather cape, for instance, may be suspended by almost any one of the feathers without danger of its shaking loose.

This cape (figs. 4, 127) is made of native-spun cotton and wild-turkey breast-feathers, while near the ends the white feathers of the shelldrake are used. The color of the body of the garment is beautifully iridescent black or bronze, the ends being varied with black and white. Strings of the cotton foundation, woven with fine duck-down, at each end permit the cape to be tied about the neck.

The small specimen (hg. 128, c) is similarly woven and ornamented with cardinal, wild-turkey, and flicker feathers. It was to form the decorated front of a pouch. These two were made by Mrs. Adams. Mrs. Langston at Mattaponi made the other two small objects (fig. 128, a, 6), one woven, like the preceding, of guinea-fowl feathers, the other, of blue ostrich-feathers, intended for a moccasin-top decoration.

Mrs. Langston says that in her mother’s time, some sixty years ago, specimens of such capes and even moccasins were not infrequent. In fact they are rather well known in both tribes by hearsay. Duck-feathers are spoken of as much used, reminding one forcibly of the references in the older literature on the southern tribes. Mrs. Langston says that the stiff ends of the plumes projecting through the inside surface of the fabric were generally trimmed off even with the textile and then the feather surface was “rubbed down until it looked like fur.”

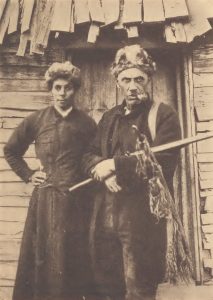

Mention here might also be made of feather capes, known as well in recent times, in which heron-feathers were simply sewed on a cloth cape in rows one above the other and overlapping. These are of course much more simple than the woven garments, but evidently none the less aboriginal. A collar of this form appears worn as part of the Indian costume in the photograph of Chief W. T. Bradby (figs. 5, 6). The use of whole duck-skins as head coverings has persisted until the present. One such, worn by Lee Major, of Mattaponi, is shown in fig. 15. Loon and heron-skins, either breasts or backs of the bird entire, were also employed. Descriptions of these articles, however, belong more appropriately under the topic of costume and ornament.

The last and perhaps the most interesting specimen to come to hand is a pair of moccasin-tops (fig. 129) made by Mrs. Adams. These are of wild-turkey breast-feathers woven on the cotton foundation in the same manner as in the cape. The feathers cover the entire top and sides of the moccasin, which is of the single instep seam type of the southern tribes, originally of deerskin, later of canvas.

For Virginia we have numerous early references and descriptions of feather weaving.

Of the Virginia Indians, Captain John Smith’s account (1612) says: ”We have seen some use mantels made of Turkey patterns, so prettily wrought and woven with tweeds that nothing could be discerned but the feathers, that was exceeding warm and very handsome.” 1

Strachey, writing in 1622, uses almost the same words as does Smith in describing this remarkable art. He refers, however, frequently to the remarkable feather technique, referring to ”cloaks of feathers,” “mantells of feathers,” and describes a certain queen of Chawopo, who entertained him, dressed in a “mantell which they call puttawus, which is like a side cloake, made of blew feathers, so artificially and thick sowed together, that it seemed like a deep purple sateen, and is very smooth and sleek.” He says these fabrics were sewed with thread of a kind of grass called pemmenaw spun between the thigh and the hands, and that not only mantles, but trousers and fish lines were made of it. 2 In another reference Strachey says that in Virginia the feather mantle was called cawassow.” 3

The extension of the feather-woven fabrics to the Hudson River is vouched for by several references to this art among the Delaware Indians of New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Swedish and Dutch authors described “ingenious suits” made of turkey-feathers overlapping, and held together by means of wild-hemp cord. 4 Skinner has compiled ethnological information concerning the Delawares of Staten Island, N. Y., in which there is reference to doublets of turkey-feathers in De Vries’ Journal and other documents.” 5

Heckewelder 6 has a description of the mantles:

Blankets made from feathers were also warm and durable. They were the work of the women, particularly of the old, who delight in such work. … It requires great patience, being the most tedious kind of work I have seen them perform, yet they do it in a most ingenious manner. The feathers, generally those of the turkey and goose, are so curiously arranged and interwoven together with thread or twine which they prepare from the rind or bark of the wild hemp and nettle, that ingenuity and skill cannot be denied them.

The most northerly record of the feather mantle is encountered in Roger Williams’ description 7 of the turkey-feather mantles of the Narragansett of Rhode Island. He remarks: ” Neyhommaua-shunck, 8 quotes several other references to the art in New England.

Among the Gulf and lower Mississippi tribes the feather technique was still more prominent, as is attested by a number of explorers and historians. The Carolina tribes of Siouan affinity were acquainted with the art, as we learn from Lawson, who in 1701 recorded it for the Santee and Catawba. 9

Lawson mentions a ”doctor” of the Santee who ”was warmly and neatly clad with a match coat, made of turkey feathers, which makes a pretty show, seeming as if it was a garment of the deepest silk shag.” 10

In another place the same author says:

Their feather match coats are very pretty, especially some of them, which are made extraordinary charming, containing several pretty figures wrought in feathers, making them seem like a fine flower silk shag; and when new and fresh, they become a bed very well instead of a quilt. Some of another sort are made of hair, raccoon, beaver, or squirrel skins, which are very warm. Others again are made of the green part of the skin of a mallard’s head, which they sew perfectly well together, their thread being either the sinews of a deer divided very small, or silk grass. When these are finished, they look very finely, though they must needs be very troublesome to make. 11

Feather mantles ”of various colors” of the tribes of the South Carolina coast, identified by Swanton as Cusabo, were mentioned by Peter Martyr. 12 Again the feather mantles were seen among the Mobile Indians in 1540 and described as follows by Ranjel: “He [the chief] also wore a pelote or mantle of feathers down to his feet, very imposing.” 13

The Creeks were adepts in the art of feather weaving, for Bartram was impressed with the beauty of cloaks woven of flamingo-feathers which he described in several of his works. 14

Du Pratz thus describes the art in Louisiana:

If the women know how to do this kind of work they make mantles either of feathers or woven of the bark of the mulberry tree. We will describe their method of doing this. The feather mantles are made on a frame similar to that on which the peruke makers work hair; they spread the feathers in the same manner and fasten them on old fish nets or old mantles of mulberry bark. They are placed, spread in this manner, one over the other and on both sides; for this purpose small turkey feathers are used; women who have feathers of swans or India ducks, which are white, make these feather mantles for women of high rank. 15

And in another place he continues:

Many of the women wear cloaks of the bark of the mulberry tree, or of the feathers of swans, turkies, or India ducks. The bark they take from young mulberry shoots that rise from the roots of trees that have been cut down; after it is dried in the sun they beat it to make all the woody part fall off, and they give the threads that remain a second beating, after which they bleach them by exposing them to the dew. When they are well whitened they spin them about the coarseness of pack-thread, and weave them in the following manner: they plant two stakes in the ground about a yard and a half asunder, and having stretched a cord from the one to the other, they fasten their threads of bark double to this cord, and then interweave them in a curious manner into a cloak of about a yard square with a wrought border round the edges. 16

Butel-Dumont also adds to the testimony by briefly describing the feather work of the natives of Louisiana as follows:

They [the women] also, without a spinning wheel or distaff, spin the hair or wool of cattle of which they make garters and ribands; and with the thread which they obtain from lime-tree bark, they make a species of mantle, which they cover with the finest swan’s feathers one by one to the material. A long task indeed, but they do not count this trouble and time when it concerns their satisfaction. 17

The feather work of the Choctaw is described by Adair as follows:

They likewise make turkey feather blankets with the long feathers of the neck and breast of that large fowl — they twist the inner end of the feathers very fast into a strong double thread of hemp, or the inner bark of the mulberry tree, of the size and strength of coarse twine, as the fibers are sufficiently fine, and they work it in manner of fine netting. As the feathers are long and glittering, this sort of blankets is not only very warm, but pleasing to the eye. 18

At Cutifachiqui similar fabrics were observed by members of De Soto’s expedition in 1540:

In the barbacoas were large quantities of clothing, shawls of thread, made from the barks of trees and others of feathers, white gray, vermilion and yellow, rich and proper for winter. 19

Later authors 20 have mentioned this elaborate art and commented upon its diffusion. Wissler suggests a Mexican center of diffusion 21 where the technique is most elaborate and equals the Peruvian work in quality and complexity. The distribution of feather work in South America is wide and the technique conforms in general with that of Peru. 22

Powhatan Feather Work Gallery

Citations:

- Smith’s account of Virginia in Tyler, L. G., Narratives of Early Virginia, New York, 1907, p. 100.[

]

- Strachey, Historic of Travaile into Virginia, pp. 58, 65, 68, 75.[

]

- Strachey, Historic of Travaile into Virginia, p. 186.[

]

- Johnson, Amandus, The Indians and their Culture as Described in Swedish and Dutch Records from 1614 to 1664, Proc. Nineteenth Internat. Congr. Americanists, Washington, 1915 (1917), p. 280.[

]

- Skinner, A. B., The Lenape Indians of Staten Island, Anthr. Papers Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist., vol. in, N. Y., 1909, pp. 40-41.[

]

- Heckewelder, John, Indian Nations, Mem. Hist. Soc. Penn., vol. xii, Philadelphia, 1876, pp. 202-3.[

]

- Williams, Roger, Key to the Indian Language, Coll. Rhode Island Hist. Soc, vol. I. Providence, 1827, p. 107.[

]

- The term is literally “turkey mantle”: néyhom (pl. –mâuogj Williams, Roger, Key to the Indian Language, Coll. Rhode Island Hist. Soc, vol. I. Providence, 1827, p. 85); –uashunck denotes a mantle or cloak.__ a coat or Mantle, curiously made of the fairest feathers of their Neyhommaûog or Turkies, which commonly their old men make; and is with them as velvet with us.” Willoughby ((Willoughby, C. C, in Amer, Anthr., vol. vii, no. 1, 1905.[

]

- Lawson, John, History of Carolina, 1714, quoted and discussed by James Mooney, Siouan Tribes of the East, Washington, 1894, pp. 70-79.[

]

- Lawson, John, History of Carolina, Raleigh ed., 1860, p. 37.[

]

- Lawson, John, History of Carolina, Raleigh ed., 1860, pp. 311-12.[

]

- Quoted by Swanton, J. R., Early History of the Creek Indians, Bull. 73, Bur. Amer. Ethnol., 1922, p. 44.[

]

- Swanton, J. R., Early History of the Creek Indians, Bull. 73, Bur. Amer. Ethnol., 1922, p. 151.[

]

- Bartram, William, Travels Through North and South Carolina, Philadelphia, 1791, pp. 502-03, and Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians (1789), in Trans. Amer. Ethnol. Soc, vol. iii, pt. 1 (1853), p. 29.[

]

- Le Page Du Pratz, Histoire de la Louisiane, English trans., London, 1763, vol. ii, pp. 191-92.[

]

- Le Page Du Pratz, Histoire de la Louisiane, English trans., London, 1763, vol. ii, p. 23.[

]

- Memoire sur la Louisiana, Paris, 1753, vol. i, pp. 154-55.[

]

- Adair, James, History of the American Indians, London, 1775, pp. 422-23.[

]

- Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto in the Conquest of Florida as told by a Knight of Elvas, translated by Buckingham Smith, New York, 1866, p. 63.[

]

- Willoughby, C. C, The Virginia Indians in the Seventeenth Century, Amer. Anthr., vol. ix, 1907, p. 69. Holmes, W. H., Prehistoric Textile Art of the Eastern United States, Thirteenth Ann. Rep. Bur. Amer. Ethnol. 1891-92, pp. 24-30.[

]

- Wissler, Clark, The American Indian, 1917, p. 61. He quotes Sahagun as the principal source for the description of this trait-complex. The most accessible treatment for Central America is that of Eduard Seler, Ancient Mexican Feather Ornaments, Bull. 28, Bur. Amer. Ethnol., 1904, and for the Maya, P. Schellhas, Comparative Studies in the Field of Maya Antiquities, ibid., pp. 611-12.[

]

- Mead, C. W., Technique of Some South American Feather Work, Papers Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist., vol. i, pt. 1, 1907. E. Nordenskicld (An Ethnogeographical Analysis of the Material Culture of Two Indian Tribes in the Gran Chaco, Gothenburg, 1919, p. 230) emphasizes the lack of data for a study of distribution in South America.[

]