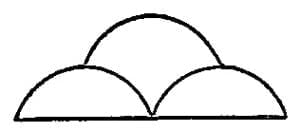

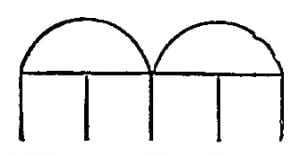

A sign for cloud is as follows: (1) Both hands partially closed, palms facing and near each other, brought up to level with or slightly above, but in front of the head; (2) suddenly separated sidewise, describing a curve like a scallop; this scallop motion is repeated for “many clouds.” (Cheyenne II.) The same conception is in the Moqui etchings, Figs. 180, 181, and 182 (Gilbert MS.)

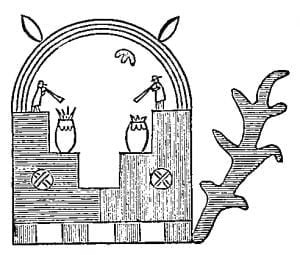

The Ojibwa pictograph for cloud is more elaborate, Fig. 183, reported in Schoolcraft, I, pl. 58. It is composed of the sign for sky, to which that for clouds is added, the latter being reversed as compared with the Moqui etchings, and picturesquely hanging from the sky.

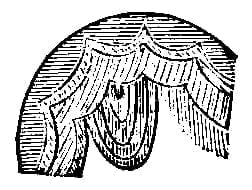

The gesture sign for rain is described and illustrated on page 344. The pictograph, Fig. 184, reported as found in New Mexico by Lieutenant Simpson (Ex. Doc. No. 64, Thirty-first Congress, first session, 1850, pl. 9) is said to represent Montezuma’s adjutants sounding a blast to him for rain. The small character inside the curve which represents the sky, corresponds with the gesturing hand. The Moqui etching (Gilbert MS.) for rain, i.e., a cloud from which the drops are falling, is given in Fig. 185.

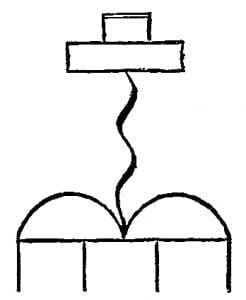

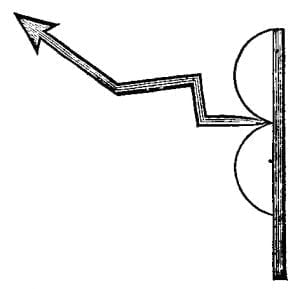

The same authority gives two signs for lightning, Figs. 186 and 187. In the latter the sky is shown, the changing direction of the streak, and clouds with rain falling. The part relating specially to the streak is portrayed in a sign as follows: Right hand elevated before and above the head, forefinger pointing upward, brought down with great rapidity with a sinuous, undulating motion; finger still extended diagonally downward toward the right. (Cheyenne II.)

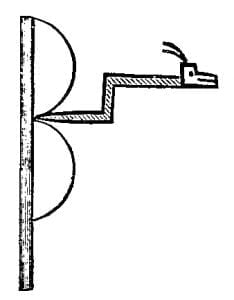

Figs. 188 and 189 also represent lightning, taken by Mr. W.H. Jackson, photographer of the late U.S. Geolog. and Geog. Survey, from the decorated walls of an estufa in the Pueblo de Jemez, New Mexico. The former is blunt, for harmless, and the latter terminating in an arrow or spear point, for destructive or fatal, lightning.

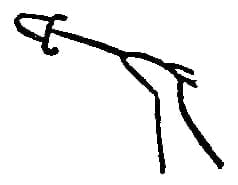

A common sign for speech, speak, among the Indians is the repeated motion of the index in a straight line forward from the mouth. This line, indicating the voice, is shown in Fig. 190, taken from the Dakota Calendar, being the expression for the fact that “the-Elk-that-hollows-walking,” a Minneconjou chief, “made medicine.”

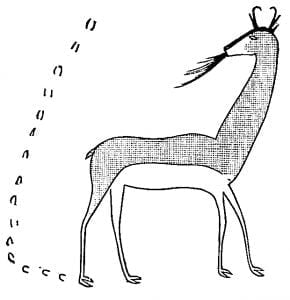

The ceremony is indicated by the head of an albino buffalo. A more graphic portraiture of the conception of voice is in Fig. 191, representing an antelope and the whistling sound produced by the animal on being surprised or alarmed. This is taken from MS. drawing book of an Indian prisoner at Saint Augustine, Fla., now in the Smithsonian Institution, No. 30664.

Fig. 192 is the exhibition of wrestling for a turkey, the point of interest in the present connection being the lines from the mouth to the objects of conversation. It is taken from the above-mentioned MS. drawing book. The wrestlers, according to the foot prints, had evidently come together, when, meeting the returning hunter, who is wrapped in his blanket with only one foot protruding, they separated and threw off their blankets, leggings, and moccasins, both endeavoring to win the turkey, which lies between them and the donor.

In Fig. 193, taken from the same MS. drawing book, the conversation is about the lassoing, shooting, and final killing of a buffalo which has wandered to a camp. The dotted lines indicate footprints. The Indian drawn under the buffalo having secured the animal by the fore feet, so informs his companions, as indicated by the line drawn from his mouth to the object mentioned; the left-hand figure, having also secured the buffalo by the horns, gives his nearest comrade an opportunity to strike it with an ax, which he no doubt announces that he will do, as the line from his mouth to the head of the animal suggests. The Indian in the upper left-hand corner is told by a squaw to take an arrow and join his companions, when he turns his head to inform her that he has one already, which fact he demonstrates by holding up the weapon.

The Mexican pictograph, Fig. 194, taken from Kingsborough, II, pt. 1, p. 100, is illustrative of the sign made by the Arikara and Hidatsa for tell and conversation. Tell me is: Place the flat right hand, palm upward, about fifteen inches in front of the right side of the face, fingers pointing to the left and front; then draw the hand inward toward and against the bottom of the chin. For conversation, talking between two persons, both hands are held before the breast, pointing forward, palms up, the edges being moved several times toward one another. Perhaps, however, the picture in fact only means the common poetical image of “flying words.”

Fig. 195 is one of Landa’s characters, found in Rel. des choses de Yucatan, p. 316, and suggests one of the gestures for talk and more especially that for sing, in which the extended and separated fingers are passed forward and slightly downward from the mouth”many voices.” Although the last opinion about the bishop is unfavorable to the authenticity of his work, yet even if it were prepared by a Maya, under his supervision, the latter would probably have given him some genuine native conceptions, and among them gestures would be likely to occur.

The natural sign for hear, made both by Indians and deaf-mutes, consisting in the motion of the index, or the index and thumb joined, in a straight line to the ear, is illustrated in the Ojibwa pictograph Fig. 196, “hearing ears,” and those of the same people, Figs. 197 and 198, the latter of which is a hearing serpent, and the former means “I hear, but your words are from a bad heart,” the hands being thrown out as in the final part of a gesture for bad heart, which is made by the hand being closed and held near the breast, with the back toward the breast, then as the arm is suddenly extended the hand is opened and the fingers separated from each other. (Mandan and Hidatsa I.)