Some of the North American tribes had an ancient custom of wrapping their dead in bark and skins, and placing them in some elevated position above ground, till the flesh was decayed, and completely separated from the bones. This was often done by depositing the corpse in a tree; or if it were a village site, on a species of scaffold. In these situations, the bodies were protected from carnivorous animals. Tribes that lived in districts of country abounding in caves that might be closed placed their corpses sometimes in these caves permanently. But several of the forest and lake tribes of ancient eras, where these advantages could not be secured, were found to place their dead in the positions indicated, above ground, till complete decomposition had supervened; when a general and final interment of the bones could be made.

There are traditions, that it was the duty of a certain class of men, called some times, “bone-pickers,” to attend to this solemn and pious task; and that it was done periodically, at intervals of time fixed by them, or denoted by custom. The tribe was called upon, when an individual died, to unite in his obsequies. His bravery, wisdom, strength, or skill in war, hunting, or council, were then recited, and the lamentations publicly celebrated. The eulogy then pronounced was final, and not renewed at the general interment.

This is the origin of those ossuaries, or trenches of human bones, which have been occasionally found in clearing up and settling the forest. The localities of such bone trenches and vaults, were universally on elevated grounds, where water from the inundation of rivers, or any common source, could not overflow or inundate the bones. A custom of this kind may be supposed to intervene, in the history of nations, between that of burning the body, which is still practiced, we are told, among the Tacullies of British Oregon, or New Caledonia, 1 and that of immediate interment, which is so generally practiced. Such a custom could not be systematically continued, by a people who were not permanently established in a country, or who, at least, were subject to be driven away by the inroads of furious tribes. And it is known to have fallen into disuse by most, perhaps by all, the tribes east of the Rocky Mountains, since the discovery and settlement of the country.

One of these ancient ossuaries, which speaks of a bygone age, and probably an expatriated people, exists on an island of Lake Huron, called Isle Ronde by the French, and Minnisäs by the Algonquins. My attention was first called to it in 1833, on making a visit to it, and examining its antique places of sepulture. The village formerly existing on this island, appears to have been abandoned about seventy years ago, when the present fort of Michillimackinac was transferred from the main land at the apex of the peninsula of Michigan, to the island bearing this name. On approaching this site, and before reaching it, my attention was struck by a quantity of dry, and very white human bones, scattered on the shore. On landing, it was perceived that the action of the waves from the southwest against the pebbly diluvial plain had exposed the end of one of these ancient ossuaries. There were bones from every part of the human body. They were traced to a trench or vault, on the level of the plain, where similar remains were observed to extend for several yards to a depth of three or four feet. In no instance were the bones of a complete skeleton found lying together, in their natural position. They were laid in promiscuously. The leg and thighbones appeared to have been packed or corded, like wood.

The state of the bones denoted a remote antiquity. None but the smaller and vesicular parts appeared to have decayed. The trees were all of secondary growth, and the ground had the appearance of once having been cleared. I inquired of an aged Ottawa Indian, without receiving much light. He said they were probably of the era of the human bones found in the caves of the island of Michillimackinac.

Having satisfied my curiosity, I proceeded to the graveyard, or ancient burial-place of the former village on the island not a hundred yards distant. Here the interments had been made in the usual manner, each skeleton occupying a separate grave. I opened several to determine this fact, as well as to verify the era of the interments. In one grave there was found a gunlock, and a fire steel, both much oxydated, and other articles of European manufacture, denoting the palmy times of the fur trade.

Ten years after these examinations, I visited a very celebrated discovery of Indian ossuaries at Beverly, twelve miles from Dundas, in Canada West. This discovery had been made about 1837, and had produced much speculation in the local papers, and many visits from antiquaries and curiosity hunters. The site is an elevated beech-tree ridge, running from north to south. The trees appear to be of the usual age and mature growth, but standing at considerable distances apart. The ossuaries are formed invariably across this ridge, and consequently extend from east to west. I examined a deposit, which measured eight feet by forty, and six feet deep. It was an entire mass of human crania, leg, thighbones, &c., in the utmost confusion. All ages and sexes appeared to have been interred together. It appeared to have been laid bare, and dug over for the purpose of obtaining the pipes, shells, and other relics with which it abounded. Ten or eleven deposits of various sizes existed on the same ridge of land, but preserving the same direction. These were not, however, all equally disturbed by the spirit of finding relics, but this spirit had been carried to a very blamable extent, without eliciting, so far as I learned, any accurate or scientific description of these interments.

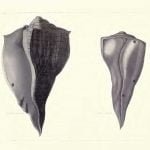

Among the articles obtained in the before-mentioned excavations, I insert drawings, (Plate 35, Figures 1 and 2,) of the full size of two species of sea-shells, the P. spirata and P. perversa; four species of antique clay-pipes, (Figures 5 and 6, Plate 8, and Figures 1 and 3, Plate 9); a worked gorget (Figure 3, Plate 19) of sea-shell, of which the original nacre of red is not entirely gone; five specimens of curious opaque-colored enamel beads, (Figures 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11, Plate 24); three baldrics of bone, (Figures 14, 15, and 16, Plate 24); four of opaque glass twisted, (Figures 12, 13, 14, and 20, Plate 25); eight different sized shell beads, (Figures 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24, Plate 24,) and eight amulets of red pipe-stone, (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, and 11, Plate 25); three of shell or bone, (Figures 7, 23, and 25, Plate 25); three of bears teeth, (Figures 26, 27, and 28, Plate 25.)

Figures 8, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, and 24, Plate 25, are minor specimens of glass or enamel.

Figures 25 and 26, Plate 24, are human teeth, used as ornaments.

There is abundant evidence that the practice of forming public ossuaries had been continued after the arrival of the French in 1608. The shells are such as must have been derived from traffic with the southern or western Indians. The pipes are of an antique and peculiar pattern, and were employed without stems: in this respect they correspond with the antique pipe from an ancient grave at Thunder Bay, Michigan, and also, it is thought, with certain pipes mentioned by Professor Dewy as found at Fort Hill, Genesee Co., N. Y. 2 The shell beads are of the same kind, precisely, as those which were discovered in the Grave Creek Mound, Virginia, as described in the first volume of the Transactions of the American Ethnological Society. 3 By the decay of the surface of the shell, which constituted their inner substance, they appear to be of the same age.

The amulets of red pipe-stone consist of bored square tubes, of the peculiar sedimentary red rock existing at the Coteau des Prairie, in the territory of Minnesota; and are identical, in material, with the cuneiform pieces of this mineral, which were dug at the foot of the flag-staff of old Fort Oswego, N. Y. 4

The colored enamel beads are a curious article. No manufacture of this kind is now known. They are believed to be of European origin, and agree completely with the beads found in 1817, in antique Indian graves, at Hamburg, Erie Co., N. Y. 5

The ancient Indians, before the introduction of European manufactures, formed baldrics for the body from the hollow bones of the swan and other large birds, or deer bones, in links of two or three inches long. These were strung on a belt or string of sinews or leather. It is believed that the relics figured are of this kind.

There were also found copper bracelets, analogous, in every respect, to those disclosed by the mounds and graves of the West. These relics denote a period of wide exchange, and great unity of manners and customs, among the ancient Indians. They link in unison the tribes of Canada, Western New York, the Mississippi Valley, and the Great Lakes. They indicate no art or degree of civilization superior to that possessed by the present race of Indians. They give no countenance to the existence, in these regions of a state of high civilization.

Citations:

- Hannan’s Travels.[

]

- Notes on the Iroquois, p. 205, 2d Edition. E. Pease & Co., Albany, 1847.[

]

- New York, Bartlett & Welford, 1835.[

]

- Notes on the Iroquois, p. 237, 2d Edition. E. Pease & Co., Albany, 1847.[

]

- Second Part of Lead Mines of Missouri. N. Y. 1819.[

]