After coming very close to driving the Colony of South Carolina into the ocean in 1715, an alliance of Southeastern indigenous peoples fell apart. 1 The tribal alliance, closest to South Carolina, the Yamasee, was decimated by 1717.

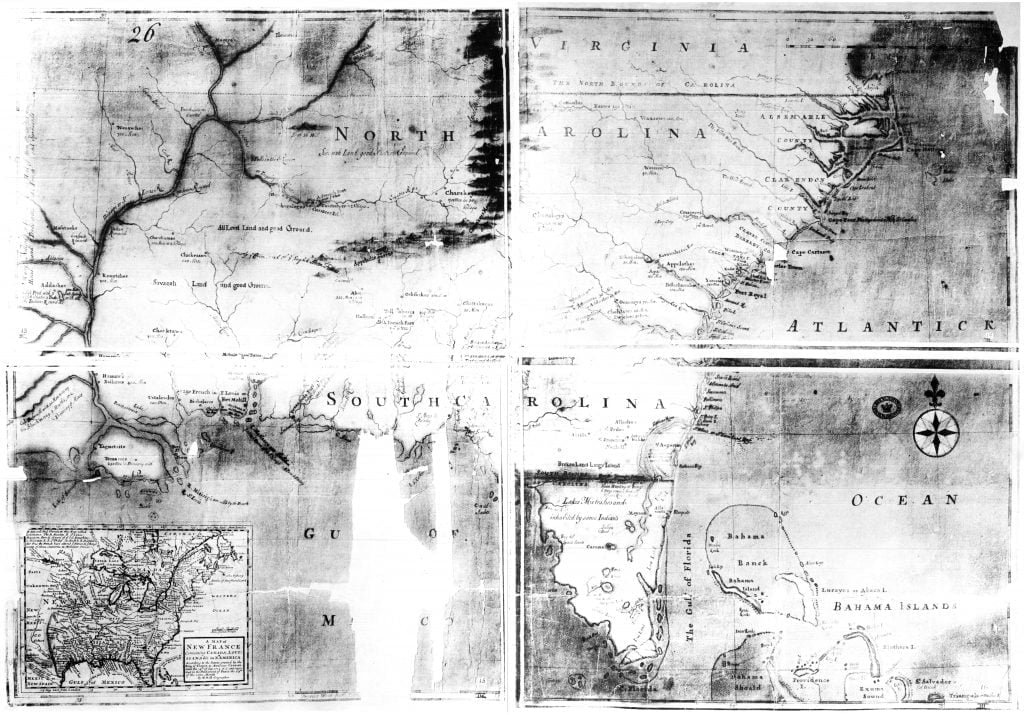

Several Creeks towns in what is now central Georgia fled to the Chattahoochee River to escape the wrath of South Carolina militiamen. 2 The three British trading posts, established in the 1680s at the shoals of the Ocmulgee near Indian Springs; in the heart of the ancient Ocmulgee Mounds near Macon, GA and near the Forks of the Altamaha in south-central Georgia, were piles of ashes.

Even though himself a major collaborator in the attacks on British traders from South Carolina, the leader of the town of Koweta, Bemarin (Emperor Brim) decided to form a new alliance that would be openly an ally of Great Britain. 3 4 He moved his town southward from near Indian Springs to the former location of Oka-mole-ke (Ocmulgee) which is now the Amerson River Park in Central Macon, GA. 5 The Creek Capital will stay at that location till the early 1740s.

The conference which included representatives from most Creek towns in present day Georgia, southeastern Tennessee and eastern Alabama met in mid-1717 at either at the new location of Koweta or near the ancient mounds on the Ocmulgee Acropolis about seven miles to the south. 6 This even is known today as the Koweta Accords and marks the creation of the modern Creek Confederacy. Unlike some earlier Creek confederacies, this alliance did not include the Alabamu and Chickasaw. Also, several Itsate Creek towns in northeast Georgia declined to join, because they would be caught in the crossfire in the ongoing war between the Creeks and the Cherokees. They formed a separate, neutral alliance of about a dozen towns and villages that became known as the Elati, which means “Foothill People.” 7

Later in 1717, leaders of the newly reconstituted Creek Confederacy met at Kweta with Carolina officials to sign a treaty. 8 This was known as the Coweta Resolution. With the exception of the province of Palachicola, which covered what is now Allendale and Barnwell Counties, South Carolina, the eastern boundary of the Creek Confederacy was to be the Savannah River. This new line caused many Creek villages in South Carolina to move westward into what is now eastern Georgia.

At the 1717 Koweta Conference, the new Creek Confederacy acquired what is now Southeast Georgia, which had not been Muskogean territory for several centuries. 9 Creeks from other regions began establishing villages and farmsteads in these newly acquired lands. The Uchee provinces along the Ogeechee River were subsequently incorporated into the Creek Confederacy and gradually thereafter lost their separate ethnic identity. 10

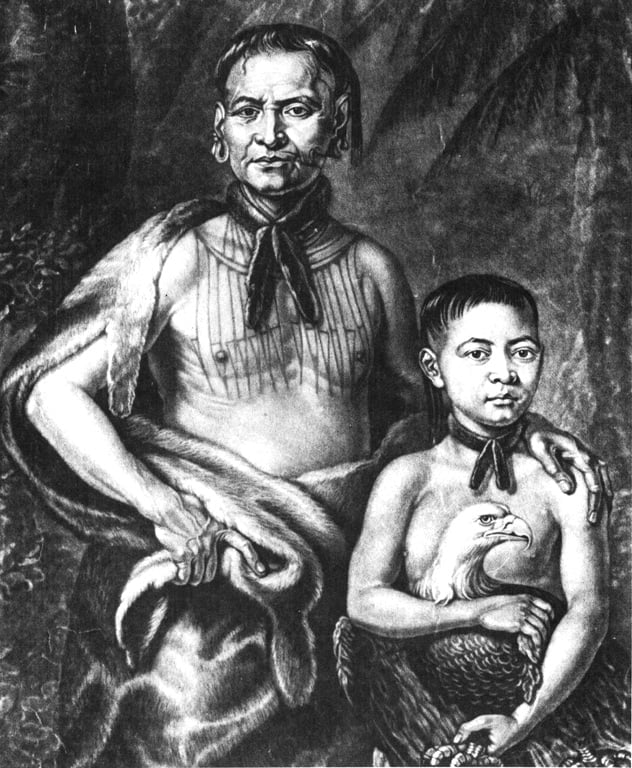

Tvmvcici (Tamachichi~Tomochichi)

Looking for a scapegoat, Emperor Brim blamed the leader of the Istate speaking Creeks in Ocmulgee Bottoms, whose principal town was Ichesi ( Ochesee in English). 11 The scapegoat’s name was Chichimako (Dog King in Itza Maya.) 12 Since most of the Dog King’s constituents along the Ocmulgee River moved to the Chattahoochee River, he was in a weak position, politically. The council of the new confederacy banished Dog King from their lands, as punishment for being involved with burning of the trading post fort on the Ocmulgee River.

When banished, Tamachichi relocated to the Lower Chattahoochee River and lived for awhile among the Apalachicola. 13 Apparently, they were not at this time part of the new Koweta Confederacy. He then moved to Palachicola on the Savannah River. Perhaps this move was mandated when the Apalachicola towns on the Chattahoochee River joined the Coweta Creek Confederacy. There was also a rumor at the time that he had run into difficulties with the French Marine garrison at Fort Toulouse.

Dog King next moved to an old Creek town, Palachicola, on the South Carolina side of the Lower Savannah River. 14 Dog King traced his ancestry to that town, when it was located where Downtown Savannah, GA sits today. Palachicola is better known to academicians by its Spanish name of Chicora.

Dog King became a trader and slave catcher. It is likely that he was involved in at least some trading activities, while living on the Ocmulgee River, but little is known about his life before 1717. Palachicola was in a ideal location to intercept escaped African slaves, headed for Spanish Florida. Dog King changed his name to Tamachichi, which is Itza Maya for “Trade Dog.” 15 Perhaps this is a colloquial word for a middleman trader.

He eventually became so prosperous that he was elected to be the leader of Palachicola. 16 By this time, Tamachichi was in his 70s or 80s and so eventually passed his leadership role on to another man.

Founding of the Province of Georgia

In late 1732, Tamachichi heard that a new British colony was planned at the mouth of the Savannah River. There are no Native American villages at this location or nearby. He led about 40 men, women and children to Yamacraw Bluff, which is about 16 miles inland from the Atlantic Ocean. 17 He later told James Oglethorpe that his ancestors were buried there. Tamachichi’s people are building a village at about the same time that the ships, carrying the first Georgia colonists, were departing from England.

In February 1733, James Edward Oglethorpe and a small delegation arrived at Yamacraw Bluff. 18 He was probably extremely surprised to see a Native village, since the site was originally selected because South Carolina officials said it was uninhabited. Nevertheless, Oglethorpe and Tamachichi got along well. Tamachichi stated that even though this is his ancestral land, he was willing to share it with the British . . . with the stipulations that his village remains on the outskirts of Savannah and that the first “emperor’s tomb (mound) remain unmolested.

Tamachichi accepted the amount of British gold sovereigns offered for his land (not beads and trinkets) and work began on the building of Savannah. In the process, Oglethorpe and Tamachichi became close friends. This genuine friendship was something that none of the other Creek leaders expected to happen.

More good fortune soon came the way of Tamachichi in 1733. His arch-enemy, Emperor Brim, died shortly after the founding of Savannah. 19 The National Council elected Chikili as the High King. Chikili had formerly been the War King of the Palachicola. Tamachichi was immediately invited to join the Creek Confederacy and annex his little Yamacraw Tribe’s land to that of the confederacy.

Trip to England

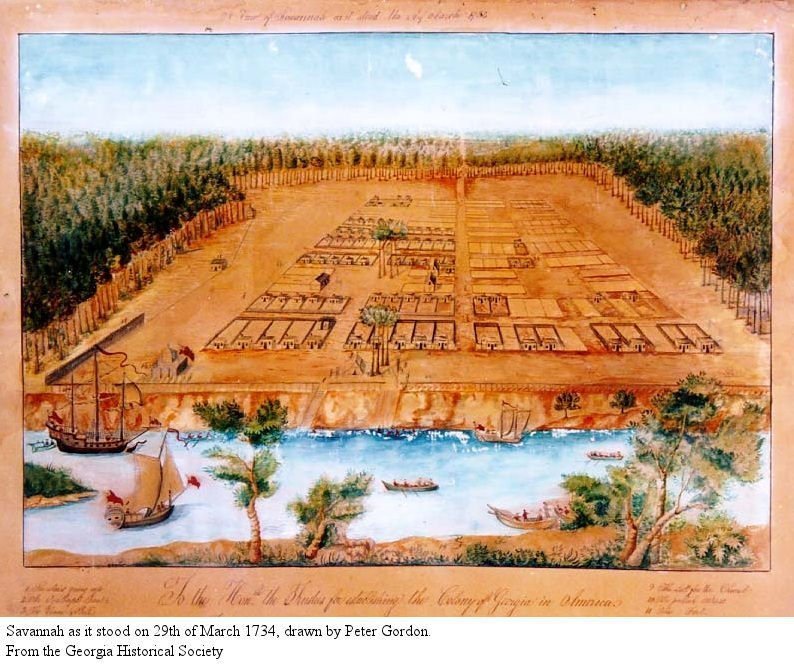

James Edward Oglethorpe was not only a brave soldier and humanitarian, but also a brilliant city planner. He personally prepared the plans for Savannah. The city produced by his design is now considered an example of outstanding city planning throughout the world. 20

In early 1734, James Oglethorpe invited Tamachichi and his immediate family to accompany him on a voyage to England. 21 While there, the Creeks were received warmly by King George II, the Georgia Board of Trustees, members of Parliament and the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Wake.

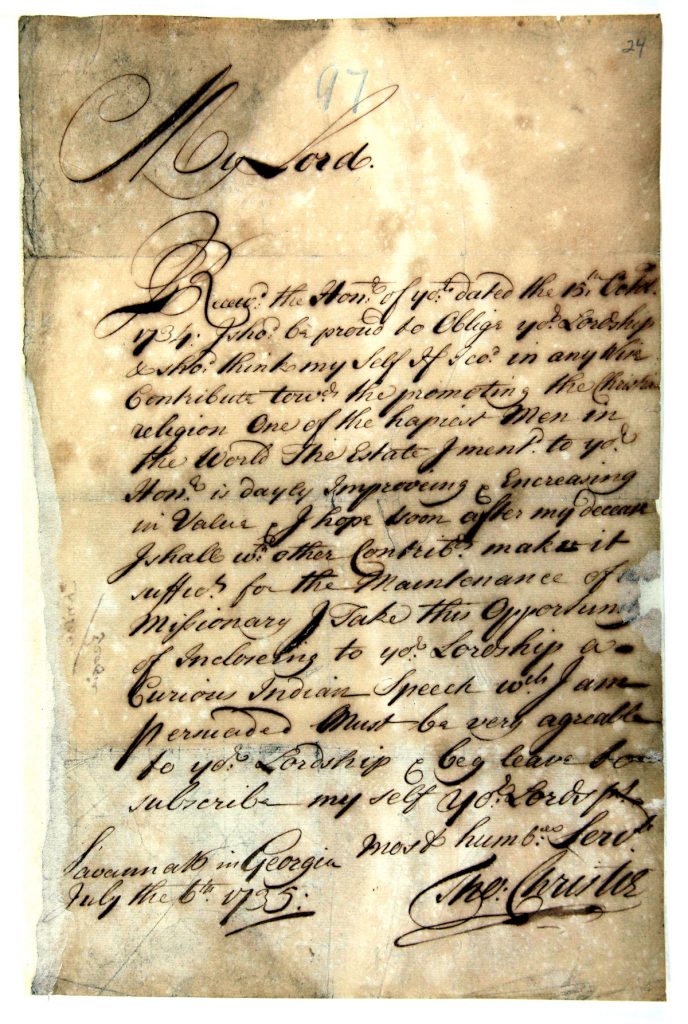

In late April 1734, the Creek delegation visited Lambeth Palace, the official home of the Archbishop of Canterbury. 22 Tamachichi was invited by the archbishop to visit his massive library, which today contains books and artifacts going back to the 600s AD. Tamachichi was so impressed by these books that he asked Wake in a letter probably penned by Thomas Christie, to send teachers to Savannah so that the children in his village would be able to read these books just like Christians could.

Wake wrote a letter to Colonial Secretary Thomas Christie about this matter. 23 The letter was sent along on the ship carrying the Creek delegation and Oglethorpe back to Savannah. Christie had been contributing to an endowment fund for the church. Wake asked about the value of the endowment and inquired if it could be used to hire missionaries for the Creek Indians. History was about to take an unexpected turn.

Conference with leaders of new Creek Confederacy

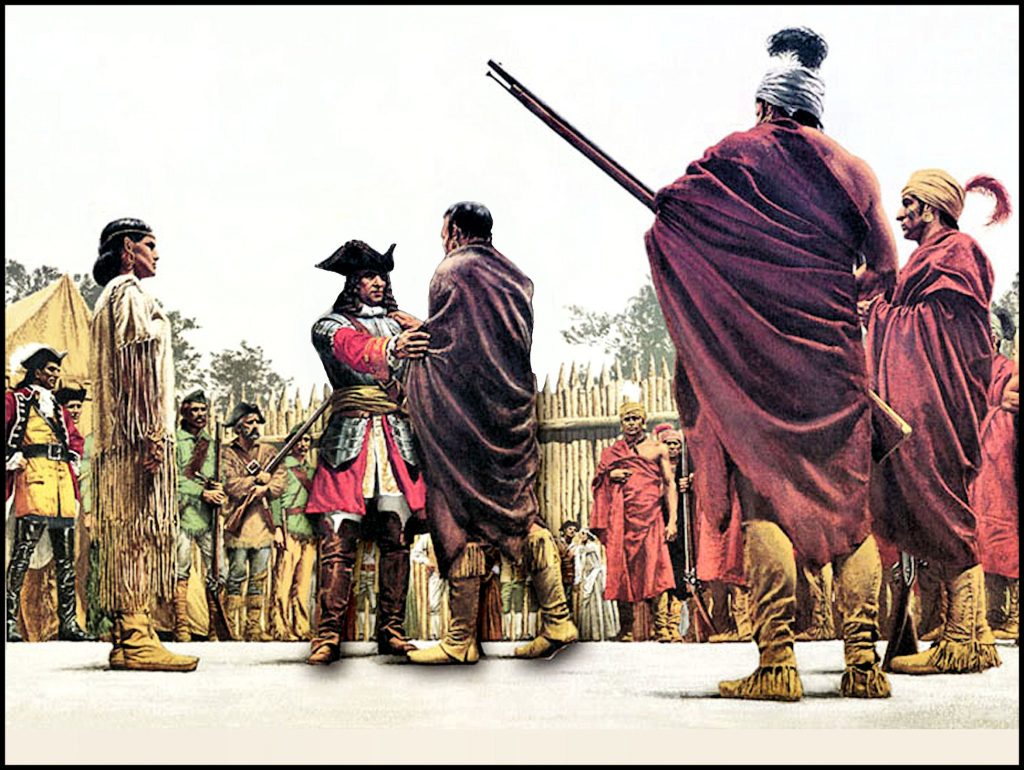

On returning to the Province of Georgia from England in early 1735 with the party of Creek Indians, led by Tamachichi (Tomochichi), James Edward Oglethorpe invited leaders of the new Koweta Confederacy, aka Creek Confederacy, to meet with colonial officials to negotiate a peace treaty. 24 Tamachichi traveled to Koweta, which at that time was on the Ocmulgee River in present day Macon, GA. He had been expelled from the new reconstituted Creek Confederacy in 1717 by Emperor Brim. Had he returned during Brim’s lifetime, he probably would have been executed. However, this time Tamachichi was welcomed, because there was a new Principal Chief, Chikili, who hailed from Palachicola, where Tamachichi lived.

Tamachichi convinced the leadership at Koweta that the colonial government, led by James Oglethorpe, was very different than that of South Carolina. He presented Oglethorpe as an honest man, who liked their people and could be trusted by their people.

Two weeks before the annual celebration on the Summer Solstice of the Muskogean New Year, aka the Green Corn Festival, a delegation of Creek leaders arrived in Savannah to meet James Oglethorpe and observe development of the town. Principal Chief, Chikili, brought with him a gift for James Oglethorpe -a buffalo calfskin velum on which was the history of the Kashete (Cusseta) a major division of the Upper Creeks. 25

Chikili read the velum in one of the Creek languages. No record survives of which one he used. As Chikili read the velum, Kvsvponakesa (Mary Musgrove) translated his words into English and Colonial Secretary, Thomas Christie, recorded the words. 26 After this presentation, Oglethorpe and the Creek leaders discussed other issues that would formalize the relationship between the new colony and the Creek Confederacy.

The Creeks authorized Oglethorpe to build a fortified trading post at the falls of the Savannah River, where Augusta, GA is now located and to build a road to that trading post. 27 At the time, British land only extended about 25 miles inland. It is not known whether James Oglethorpe originally requested to rebuild the fortified trading post at Ocmulgee Bottoms. Perhaps both parties concluded that having a British outpost in the heart of the Creek Confederacy might be a source of future conflict.

The Creek delegation met with colonial leaders on June 7, 1735. 28 Chikili again read the buffalo calfskin to the leaders, while Mary Musgrove translated and Thomas Christie wrote down the minutes. The discussions of military alliances and construction of a fortified trading post on the Fall Line were not discussed at this meeting.

The velum was then given to Supervising Trustee, James Oglethorpe. Oglethorpe realized that he had in his possession extraordinary documents, which proved that at least one American Indian people were literate. He directed Christie to polish his minutes from Chikili’s presentation and send both the minutes and the buffalo velum to England on the next available ship. 29 Christie wrote a cover letter for both the velum and its translation, which is contained in subsequent sections.

It is not clear if Oglethorpe accompanied the velum and letter on the ship. The authors of pre-2015 essays about the Migration Legend did not seem to be aware that Oglethorpe sailed to England in the summer of 1735. We know this because of an article in a popular British magazine of the time. 30

“This Morning James Oglethorpe, Esq; accompanied by the Rev. Mr John Wesley, Fellow of Lincoln College, the Rev. Mr. Charles Wesley, Student of Christ Church College, and the Rev. Mr. John Ingram of Queens College, Oxford, set out from Westminster to Gravesend, in order to embark for the Colony of Georgia – Two of the aforesaid Clergymen design, after a short stay at Savannah, to go amongst the Indian Nations bordering that Settlement, in order to bring them to the Knowledge of Christianity.”

Gentleman’s Magazine – October 14, 1735

The Migration Legend in England

The arrival of the Creek Migration Legend and its English translation created an immediate stir in London. Excerpts of the document were published in several London newspapers. 31 The most extensive coverage was in the American Gazetteer:

“This speech was curiously written in red and black characters, on the skin of a young buffalo, and translated into English, as soon as delivered in the Indian language. . . . The said skin was set in a frame, and hung up in the Georgia Office, in Westminster. It contained the Indians’ grateful acknowledgments for the honors and civilities paid to Tomochichi, etc.”

Note that the description states . . . “written in red and black characters.” This was an abstract writing system, not pictographs as normally seen on much more primitive communication systems used by other tribes in North America.

In his 1881 book on the Creek Migration Legend, Smithsonian Institute ethnologist, Albert Samuel Gatschet wrote: 32

“Upon the request of Dr. Brinton, Mr. Nicholas Trubner made researches in the London offices for this pictured skin, but did not succeed in finding it. He discovered, however, a letter written by Tchikilli, dated March, 1734, which is deposited in the Public Record Office, Chancery Lane.”

He also stated: 33

“The chances of rediscovering the original English translation of the Migration Legend of the Creek People are therefore almost as slim as recovering the lost books of Livy’s History” (Roman historian)

Much of the English text of Chikili’s speech was translated into German and published in Germany. Albert Gatschet wrote: 34

“A translation from the English has been preserved in a German book of the period, and the style of this piece shows it to be an authentic and comparatively accurate rendering of the original. The German book referred to is a collection of pamphlets treating of colonial affairs, and published from 1735 to 1741; its first volume bears the title: Aiisfuehrliche Nachrichtvonden Saltzburgischen Bmigranten, die sich in America niedergelassen haben – Worin, etc. etc., Herausgegeben von Samuel Urlsperger, Halle, MDCCXXXV. The legend occupies pp. 869 to 876 of this first volume, and forms chapter six of the “Journal” of von Reck, the title of which is as , follows : Herrn Philipp Georg Friederichs von Reck Diarium von Seiner Reise nach Georgien im. Jahr 1735. F. von Reck was the commissary of those German-Protestant emigrants whom religious persecution had expelled from Salzburg, in Styria, their native city.”

When the original document, written by Thomas Christie, was finally discovered in 2015, the translation of the German text was found to be not so accurate or complete as Gatschet had presumed. Although the texts of the two documents follow the same general pattern, there were changes made in some of the passages that completely changed the meanings of certain phrases and sentences. Also, some sentences were presented in reverse order.

After Albert Samuel Gatschet wrote the book on the Creek Migration Legend, virtually all scholars assumed that if a Smithsonian Institute ethnologist from Germany could not find the original Migration Legend, it obviously did not exist. There are no published records of further searches in the 20th century. Both famous scholars such as John Swanton, plus a legion of historians and anthropologists merely cited Gatschet after stating that the original documents were long gone.

Citations:

- Green, William, Chester B. DePratter, and Bobby Southerlin. (2001) “The Yamasee in South Carolina: Native American Adaptation and Interaction along the Carolina Frontier.” Another’s Country: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on Cultural Interactions in the Southern Colonies. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press; p. 13-17.[↩]

- Green, William, Chester B. DePratter, and Bobby Southerlin. (2001) “The Yamasee in South Carolina: Native American Adaptation and Interaction along the Carolina Frontier.” Another’s Country: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on Cultural Interactions in the Southern Colonies. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press; p. 13-17.[↩]

- Bemarin was the name of the old Apalache Province where Coweta was located. Its name can be seen on maps by Guilaume DeLisle.[↩]

- Sweet, Julie A. “Brims (d. 1733).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 07 March 2013.[↩]

- The changed location of Coweta can be observed by comparing the 1715 Richard Beresford Map of Carolina with the 1721 John Barnwell Map of Carolina.[↩]

- Hahn, Steven C. (2004) The Invention of the Creek Nation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; p. 29-30.[↩]

- Thornton, Richard (April 28, 2015) “The Elate: a Native American people erased from history.” People of One Fire.[↩]

- Peach, Stephen J. (2013) “Creek Indian Globetrotter: Tomochichi’s Trans-Atlantic Quest for Traditional Power in the Colonial Southeast.” Ethnohistory, 60(4), 605-635.[↩]

- Maps of Georgia’s Coastal Region from 1562 until 1721 contain very few town or village names, which are Muskogean words.[↩]

- Until about 1751, there was an extensive Uchee population in what is now Allendale County, SC, plus Effingham and Screven Counties, GA. Their presence is reflected in several geographical names such as Uchee Reserve Road in Allendale County. Allendale still contains a considerable number of biracial and tri-racial Uchee descendants. See “Petition for state recognition – Savannah River Band of Uchee People.”[↩]

- Peach, Stephen J. (2013) “Creek Indian Globetrotter: Tomochichi’s Trans-Atlantic Quest for Traditional Power in the Colonial Southeast.” Ethnohistory, 60(4), 605-635.[↩]

- Tamachichi is entitled Dog King in the original Migration Legend cover letter.[↩]

- Peach, Stephen J. (2013) “Creek Indian Globetrotter: Tomochichi’s Trans-Atlantic Quest for Traditional Power in the Colonial Southeast.” Ethnohistory, 60(4), 605-635.[↩]

- Peach, Stephen J. (2013) “Creek Indian Globetrotter: Tomochichi’s Trans-Atlantic Quest for Traditional Power in the Colonial Southeast.” Ethnohistory, 60(4), 605-635.[↩]

- Institutio Linquistico de Verana (1973) Dicccionario Totonaco de Papantla, Vera Cruz. The Itza Maya spoken a thousand years ago, when Itza refugees were coming to southeastern North America was much closer to Totonac than today. The Itza’s had been subjects of the Totonacs for several centuries.[↩]

- Peach, Stephen J. (2013) “Creek Indian Globetrotter: Tomochichi’s Trans-Atlantic Quest for Traditional Power in the Colonial Southeast.” Ethnohistory, 60(4), 605-635.[↩]

- Peach, Stephen J. (2013) “Creek Indian Globetrotter: Tomochichi’s Trans-Atlantic Quest for Traditional Power in the Colonial Southeast.” Ethnohistory, 60(4), 605-635.[↩]

- Sullivan, Buddy. “Savannah.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 26 May 2015.[↩]

- Sweet, Julie A. “Brims (d. 1733).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 07 March 2013.[↩]

- The plan of Savannah and the photographs of the city today can be found in city planning textbooks of universities around the world.[↩]

- Sweet, Julie A. “Tomochichi (ca. 1644-1739).” New Georgia Encyclopedia.[↩]

- Peach, Stephen J. (2013) “Creek Indian Globetrotter: Tomochichi’s Trans-Atlantic Quest for Traditional Power in the Colonial Southeast.” Ethnohistory, 60(4), 605-635.[↩]

- Wake’s letter is referred to in the opening paragraph of the Migration Legend’s cover letter.[↩]

- Peach, Stephen J. (2013) “Creek Indian Globetrotter: Tomochichi’s Trans-Atlantic Quest for Traditional Power in the Colonial Southeast.” Ethnohistory, 60(4), 605-635.[↩]

- Albert Gatshet and others, who have written about the Migration Legend in the past, seemed to be unaware that the Kaushete were the same people as the Cusate, described by French explorers and the Cusseta, described by British officials.[↩]

- “The American Gazetteer.” London, 1762, vol. II, Article on Georgia.[↩]

- Cashin, Edward J. “Augusta.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 05 August 2015.[↩]

- Christie, Thomas (1735) Cover letter for Migration Legend, dated July 6, 1735.[↩]

- Gatschet, Albert Samuel (1884) A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians. Philadelphia: D. G. Brinton Publishers; pp. 235-6.[↩]

- Gentleman’s Magazine. London, England. October 14, 1735.[↩]

- Gatschet, Albert Samuel (1884) A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians. Philadelphia: D. G. Brinton Publishers; pp. 236.[↩]

- Gatschet, Albert Samuel (1884) A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians. Philadelphia: D. G. Brinton Publishers; pp. 236.[↩]

- Gatschet, Albert Samuel (1884) A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians. Philadelphia: D. G. Brinton Publishers; pp. 236.[↩]

- Gatschet, Albert Samuel (1884) A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians. Philadelphia: D. G. Brinton Publishers; pp. 236.[↩]