Mary Anderson Longboat, an Indian of the Six Nations Reservation, says the following of this remarkable woman: “We of the Six Nations Reserve, honour our Indian poetess, Emily Pauline Johnson. She is more than just a memory, for she lives today in her books which are read throughout the world. In her lifetime, her recitations were equally famous. We are especially proud that she boasted her nationality, and in her native buckskin costume was accepted, even by royalty.

As a poetess, Miss Johnson was not great, not a Tennyson nor a Browning, but as Gilbert Parker writes, “Canadian Literature would have been the poorer without her contribution.” Mr. Bernard McEvoy describes her as “a literary worker of whom Canada may well be proud.”

She lived close to nature, worshipping the rippling waters of the Grand River, the woods and its stately trees, seeing beauty in all of her surroundings. Hence we have so many musical, happy poems such as “The Song My Paddle Sings,” “Rainfall,” “Moonset” and in “Shadow River” is reflected the beauties of Muskoka. Her pride in her Indian ancestry brought about her racial poetry, a novelty to Canadian art, for in these she sings the praise and glories of her race, tells of old traditions the injustices and wrongs and begs for an understanding of her people.

In later life, Pauline Johnson began to develop prose writings devoting one book entire’s to legends. She treasured these old Indian legends as something really belonging to her people and took it upon herself to rescue them from oblivion. They were never written, but handed down by word of mouth from generation to generation since the immemorial past, She traveled across Canada visiting many tribes to hear old chieftains relate in broken English these strange mysterious myths.

Her father was George H. Martin Johnson, once Government interpreter and Head Chief of the Six Nation Council. Her grandfather, John Smoke Johnson was famous for his colorful oratory and was known as “The Mohawk Warbler.” Miss Johnson was born and raised on her father’s estate called “Chiefswood” which is situated on the banks of the Grand River near Middleport, Ontario. She was quite young when she was encouraged by her parents to write verses and to delve into worthwhile books. Poetry greatly appealed to her, and it is recorded that before she was twelve she had read works by Shakespeare, Longfellow, Scott, Byron and other famous writers.

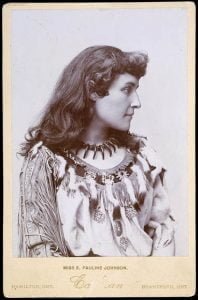

To earn livelihood she appeared on public platforms wearing a fringed buckskin suit and jewelry carved by Mohawk silversmiths, a wampum belt, a necklace made of the claws of the Cinnamon bear, a scarlet blanket thrown around her shoulders and a single plume in her long, flowing tresses. These public appearances took her to London, England, Where she became a social success. She was received at Buckingham Palace by the late King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra.

An account following the death of H. R. H. the Duke of Connaught once Governor- General of Canada tells of a long life friendship between the poetess and the Duke. It began when as a girl of eight, she attended the ceremony in which he was made Honorary Chief of the Mohawks and a member of the Six Nations Council. He knelt on a magnificent scarlet broadcloth blanket. Twenty five years later he attended one of her recitals in London and asked what had become of this blanket. She told him it was the scarlet mantle she used in her stage costume. Some years later, on an official tour of Vancouver, he visited her in a hospital where she was dying. She arranged to have the scarlet blanket draped over the chair in which he sat. This was a glorious memory to her remaining months. She passed away in March, 1913 and one of the first telegrams of regret was from Rideau Hall.

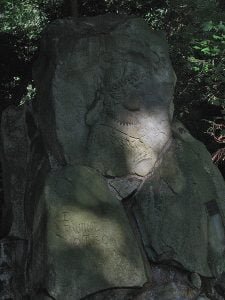

After her death, her body was cremated in accordance with a wish she had expressed. Some of the ashes were sprinkled on Siwash Rock in Vancouver and upon the waters around it. The urn containing the ashes was placed in a plot in Stanley Park where a monument has been erected to her memory. It is made of rough boulders taken from the sea and upon one stone is carved a remarkable likeness of her. A memorial fountain is also erected to her memory. On one side are shown flint and feather and on the other side, canoe and paddle. These memorials serve as national tributes to her and visible marks of public esteem.”

THE CORN HUSKER

By Pauline Johnson-Tekahoniwake

Hard by the Indian lodges, where the bush

Breaks in a clearing, through ill-fashioned fields,

She comes to labor, when the first still hush

Of Autumn follows large and recent yields.

Age in her fingers, hunger in her face,

Her shoulders stooped with weight of work and years

But rich in tawny coloring of her race,

She comes a-field to strip the purple ears,

And all her thoughts are with the days gone by,

Ere Might’s injustices banished from their lands

Her people, that to-day unheeded like,

Like the dead husks that rustle through her hands.

Leaving the monument of Pauline Johnson, the Mohawks headed for the nearby City of Brantford and the grave of Governor Blacksnake.