Until the late 1700s, the region of the Southeastern United States occupied by the Creek Indians was divided up into provinces known as ekvn-warkv (ē-kăwn-wăr-kăw.) Originally, they had functioned like separate nations with distinctive languages or dialects. However, after diseases introduced by European explorers killed off most of the people, the districts functioned more like modern-day counties. Each province had a capital, known as a talwamiko in Mvskoke (Muskogee) or olamako in Itsati (Hitchiti) or Koasati. Provincial capitals functioned as regional depositories for food reserves, bulk materials & armaments, shrines for religious festivals and permanent locations for seasonal or open air markets.

Until the late 1700s, the region of the Southeastern United States occupied by the Creek Indians was divided up into provinces known as ekvn-warkv (ē-kăwn-wăr-kăw.) Originally, they had functioned like separate nations with distinctive languages or dialects. However, after diseases introduced by European explorers killed off most of the people, the districts functioned more like modern-day counties. Each province had a capital, known as a talwamiko in Mvskoke (Muskogee) or olamako in Itsati (Hitchiti) or Koasati. Provincial capitals functioned as regional depositories for food reserves, bulk materials & armaments, shrines for religious festivals and permanent locations for seasonal or open air markets.

The most important function of the government leaders in a province was to assure a year round supply of food and raw materials. This was accomplished both by guiding farmers to practice productive farming methods and by storing sufficient food in reserve to supply families and villages when crops failed or were destroyed from natural causes.

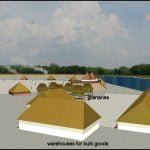

The food reserves were acquired by several means. In addition to their own fields, families were expected to help plant, cultivate and harvest fields that belonged to the village or province. These food reserves were stored in large warehouses in the capital of the province. Subordinate villages furnished food reserves to their district administrative center’s warehouse that was known as a talula in Itsati and a talufa in Mvskoke. Individual households might be expected to contribute some of their food supplies to feed the members of the government and artisans, who worked full time at professional or administrative positions.

In times of famine, the government officials of Creek provinces were expected to share fully with the common people. This apparently was not the case in all Native American provinces in the Southeast. Archaeologists have found evidence in excavated skeletons that the diet of commoners in the Mississippi Valley often suffered from nutritional deficiencies while the elite families of towns enjoyed much more healthful diets.

Grains and semi-perishable foods were stored in special barns raised on poles. They could only be accessed by ladders, but were also much less vulnerable to rodents and molds. The walls of the granaries were composed of vertical river cane slats that functioned very similarly to screen porches.

The provincial government also stored bulk goods like salt, leather, paint pigments, furs, cloth, fibers for making cloth, dyes for coloring cloth and pure copper sheets. The provincial government also maintained armories where bows, arrows, war clubs, copper hatchets and spears were manufactured then stored for use during war.

The early Spanish explorers such as those in the Hernando de Soto Expedition (1539-1543) described large warehouses up to 200 feet long, which stored the goods and weapons of provinces. Apparently, the warehouses were built on the ground like large houses, but were located near water transportation so bulk goods could be easily transported from large cargo canoes to the warehouse.