One of the purposes of the Juan Pardo Expedition in 1566-67 was to locate deposits of gold and silver for the King of Spain. Silver ore was found in the vicinity of the Nantahala Gorge in what is now North Carolina. The chronicler of the Pardo Expedition noted that gold was in abundance in what is now called the Blue Ridge Mountains. Most European maps of the 1600s specifically noted the region in Georgia where gold was present.

The readily available Spanish colonial archives are completely silent about gold prospecting activities in the Georgia Mountains. However, Spanish gold claims have been found on Nickajack Creek in Smyrna, GA northwest of Atlanta. 16th or 17 century Spanish armor and artifacts have been found both near Ellijay, GA and Dahlonega, GA in the primary gold bearing zone. Neither de Soto not Pardo probably traveled through these valleys. When the first gold mining operations began on Dukes Creek, near the Nacoochee Mound, the miners found the ruins of a European village and numerous iron tools typical of the Spanish in the 1600s. They also found a Spanish cigar mold! (See Examiner article, Sleeping in the Shadow of an Old Spanish Silver Mine.)

The European village was probably built by Spanish Melungeons in the late 1500s or early 1600s. The Melungeons were a mixed-heritage people composed of forcibly converted Jews and Moslems, escaped North African galley slaves, and their Indian spouses, who lived in the Southern Highlands to avoid the poisonous eyes of the Spanish Inquisition. They were still working gold and silver in some parts of the Highlands in the late 1700s. A party of Shenandoah County, VA settlers led by John Sevier and Col. John Tipton, passed through several Melungeon villages in northeastern Tennessee. Approximately, 250,000 Melungeon descendants still live in the Southern Highlands. The Melungeons in Georgia probably moved to Louisiana after Spain took it over in 1763.

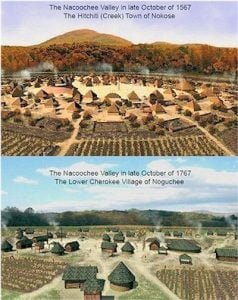

The best archival evidence that the Nacoochee Valley was occupied during the 1600s by both Spanish Melungeon gold miners and a remnant Creek population comes from English colonial archives. A joint scouting party of English soldiers and Chorakees climbed to the top of Tray Mountain and beheld numerous smoke plumes rising from the Nacoochee Valley. The Chorakees told the English that the smoke was from numerous gold smelting operations being run by the Spanish. At this point, the English archives are henceforth silent on the Nacoochee, but undoubtedly the English provided inducements for the Chorakees to massacre the Spanish.

Chorake means splinter group in Muskogee-Creek. They were not Algonquian Cherokees as later typified the North Carolina Mountains, but were allied with them and gave the real Cherokees their English name. In 1690, they would have spoken a hybrid language that mixed Creek with some Catawba and Yuchi words.

The First Cherokee Occupants of the Nacoochee Valley

Beginning about four years ago, an alliance of Creek scholars around the nation, known as the People of One Fire, began closely examining all Spanish, French & English colonial maps and archives, then analyzing Native words they contained with Hitchiti, Muskogee, Koasati, Alabama, Cherokee and Maya dictionaries. The group has determined that from the early 1700s till the late 1700s, northeast Georgia was occupied by Chorakee members of the Cherokee Alliance, who spoke a hybrid Creek dialect. All of the Cherokee town names in northeast Georgia and northwest South Carolina are either Creek, Siouan or Yuchi words. None can be translated by the Cherokee language.

There is a state historical marker near the Nacoochee Valley that tells of a massive battle on Blood Mountain (near the Nacoochee Valley) in 1755 between the Cherokees and Creeks to gain control of northern Georgia. The sign is historical malarkey. Locals talk of large numbers of arrowheads found in Slaughter Gap on Blood Mountain, as proof of the story.. However, by 1755 all tribes in the region were totally dependent on muskets and gunpowder furnished by White traders.

In 1755 both the colonies of South Carolina and Georgia claimed what is now Georgia north of Macon. South Carolina was allied with the Chorakee Cherokees. Georgia was allied with the Creeks. South Carolina gave Creek lands in what it claimed was its colonial territory in return for the Cherokees going to war against the French and their Indian allies.

An army of Overhills Cherokees and British Rangers overran the villages of Georgias Creek allies in what is now northwest Georgia. However, the very next year an army of Upper Creeks allied with France drove the Cherokees out of NW Georgia, and began systematically destroying Overhills Cherokee towns in what is now Tennessee. Within two years the Overhills Cherokees were sending out peace feelers and offers to join with France. The Tamatli branch of the Overhills Cherokees did formally become French allies. The Upper Creeks held all of northwestern Georgia until 1763 when France surrendered and gave up all its lands in what is now the Southeastern United States.

An army of Lower Cherokees (Chorakees) and Middle Cherokees attacked Georgias Chickasaw, Apalachee and Creek allies in northeastern Georgia. In 100% contrast to the state historical marker, they were defeated. In fact, a map prepared in 1756 by Professor Mitchell (who gave Mt. Mitchell its name) showed all the Cherokee towns in the Nacoochee Valley burned, plus all those near modern day, Clayton, GA, Hiawassee, GA, Hayesville, NC, Murphy, NC and Franklin, NC. These towns were never rebuilt.

In 1757, a series of incidents caused by cultural misunderstandings, enflamed, when several Cherokee leaders unwisely taken as hostage, were murdered without provocation. It has been a pervasive rumor for over two centuries that British authorities sent blankets to Cherokees saturated with the pus of smallpox victims after the Redcoats heard rumors of a Cherokee defection to the French.

The Cherokees ceased to be allies of Great Britain and attacked the South Carolina frontier across a wide front. The surprise attack was initially devastating to the frontier, but a combined army of Redcoats, militia, Catawbas and South Carolina Creeks invaded the mountains and destroyed most of the remaining Lower and Middle Cherokee towns. The Cherokees surrendered. They lost all of their territory in North Carolina east of a line running through Murphy, NC in the 1763 treaty. The invincibility of Cherokee warriors as portrayed by Georgia State Historical Markers in the vicinity of the Nacoochee Valley, seems to be a little out of touch with historical facts.

The second Cherokee occupation of the Nacoochee Valley

Up until the American Revolution, English maps continued to show Cherokee villages with Creek Indian names in northeast Georgia. Most of the Cherokee villages destroyed in 1755 were never rebuilt. In fact, maps from the era between 1763 and 1776 only show four Cherokee villages in Georgia: Noguchee and Chota in the Nacoochee Valley; Long Swamp Creek on the Etowah River in what is now Pickens County, GA, and Tugaloo on the Savannah River in what is now Stephens County, GA.

After the American Revolution, there was a sudden ethnic change in northern Georgia. The Cherokees had foolishly become allies of the British. Most Cherokee bands were thoroughly defeated in 1776. The defeated Cherokees were forced to flee southward and westward for their lives. From numbering a few hundred in 1775, the Cherokee population swelled to over 10,000 in Georgia. At that time, numerous villages with Algonquian-Cherokee names appeared.

Chota is the Creek word for frog. The original Georgia Cherokee village of Chota was located between the Nacoochee Valley and Blood Mountain. After the Revolution, maps show that the name of the village has changed to Walasiyi, which Algonquian Cherokee for place of the frog. There are also many new Cherokee villages in and around the Nacoochee Valley. Some had Algonquian names like Chostoe (Rabbit) and Yonah (Bear.) Others had names of Creek origin such as Saute, Enota, Tallulah (town,) Yahoola (council speaker), etc.

In 1793 the Cherokees gave up their lands east of the Nacoochee Valley. Much of the population soon concentrated in the broad river valleys of northwest Georgia. The Cherokee population of the Nacoochee Valley never was very large, and soon began to decline..

The Lower Cherokees were wiped out as a distinct ethnic group by smallpox and the wars that occurred between 1755 and 1783. The 1757 smallpox epidemic in the alone killed an estimated 1/3 of the total Cherokee population. Their hybrid Creek-Catawba-Yuchi-Algonquin language has completely been forgotten. It is highly unlikely that any contemporary Cherokee could understand any of it. The language only survives as the names of hundreds of small towns, forested mountains and a few rivers.