The Southwestern regions of North America present a most extensive and interesting field for antiquarian research. The long-continued existence of powerful, civilized, and populous races is fully proved by the occurrence of almost innumerable ruins and national relics. Even in the sixteenth century, the Spanish invaders found these regions in the possession of a highly prosperous and partially civilized people. Government and social institutions were upon that firm and well-defined basis which betokened long continuance and strong national sentiment. In many of the arts and sciences, the subjugated races were equal, and in others superior, to their Christian conquerors. Their public edifices and internal improvements were on as high a scale, and of as scientific a character, as those of most European nations of the day.

The fanatical zeal of Cortez and his successors destroyed invaluable records of their history and nationality; and many of their most splendid edifices fell before the ravages of war and bigotry; yet numerous structures still exist, though in ruins, attesting the art and industry of their founders. Pyramids, in great numbers, still rear their terraced and truncated surfaces through the land. In the first fury of the conquest, the great Teocalli, or Temple of the city of Mexico, was leveled to the ground, and we can only learn by the description of its destroyers, with what pomp and ceremony the Mexicans celebrated on its summit the rites of their sanguinary worship. The colossal figures of the sun and moon, covered with plates of gold, the hideous stone of sacrifice, and the terrible sound of the great war-drum, are mingled with strange fascination of description in the pages of the early chroniclers.

In the city of Tezcuco, which is said to have contained a hundred and forty thousand houses, are the remains of a great pyramid, built of large masses of basalt, finely polished and curiously sculptured in hieroglyphics. Other similar edifices in the neighborhood are composed of brick. The enormous structure of Cholula, covering a surface twice larger than the great Egyptian pyramid, but truncated at half its altitude, still, in its ruins, excites the admiration of travelers.

A still more extraordinary effort of semi-civilized industry is to be found in the celebrated Xochicalco, or ” House of Flowers,” situated on the plain of Cuernavaca, more than a mile above the level of the sea. It appears to be a natural hill, shaped in a pyramidal form by human labor, and divided into four terraces. It is between three and four hundred feet in height, and nearly three miles in circumference.

Eight leagues from the city of Mexico are the two celebrated pyramids of Teotihuacan, sacred, according to tradition, to the deified sun and moon. The larger has a base nearly seven hundred feet in length, and is a hundred and eighty feet in height. They are faced with stone, and covered with a durable cement. These pyramidal structures may be estimated by thousands in the South western provinces of this continent.

The ruins of ancient cities, in the same region, are extremely numerous, and every thing evinces the former existence of a swarming and industrious population. In Tezcuco and its vicinity are the remains of very magnificent buildings and aqueducts. At Mitlan, in the district of Zapoteca, occur specimens of architecture of the most imposing character. Six porphyry columns, each, nineteen feet in height, and of a single stone, decorated the interior of the principal building. Elaborate Mosaic work and illustrative paintings abound, strongly resembling some of the classical antiquities.

The ruins of Palenque, in Chiapa, are among the most extensive and remarkable. Here formerly stood a great city, the remains of which can be traced, it is said, over a space six or seven leagues in circumference. Much elaborate sculpture, exhibiting curious historical reliefs, is discovered in the forsaken apartments of the ancient palaces and temples. These represent human sacrifices, dances, devotion, and other national customs. The richly-carved figure of a cross excites surprise and speculation the same emblem having been discovered elsewhere, as well as in Northern America.

Many surprising remains, both of erection and excavation, are to be found near Villa Nueva, in the province of Zacatecas. A rocky mountain has been cut into terraces, and extensive ruins of pyramids, causeways, quadrangular enclosures, and massive walls are still standing.

At Copan, in Honduras, among many other remarkable works, are found numerous stone obelisks, of little height, covered with hieroglyphical representations. The relics of a fantastic idolatry are frequent. “Monstrous figures are found amongst the ruins; one represents the colossal head of an alligator, having in its jaws a figure with a human face, but the paws of an animal; another monster has the appearance of a gigantic toad in an erect posture, with human arms and tiger s claws.” At the time of the Spanish conquest, Copan was still a large and populous city. It is now utterly deserted.

The extensive ruins of Uxmal or Itzlan, in Yucatan, have been, ever since the memory of man, overgrown with an ancient forest. At this place is a large court, pared entirely with the figures of tortoises, beautifully carved in relief. This curious pavement consists of more than forty-three thousand of these reptiles, much worn, though cut upon very hard stone. A large pyramid and temple are still standing, containing some elegant statues, and, it is supposed, the representation of the elephant. Great mathematical accuracy and adhesion to the cardinal points distinguish the relics of this city.

Many other extraordinary remains might be cited. The works of the Mexican nation, such as it was found by the Spaniards, were of a massive and enduring character. Extensive walls, designed for a defense against foreign enemies; large public granaries and baths, with admirable roads and aqueducts, evinced a degree of power and enlightenment to which the colored races have seldom attained.

Sculpture and elaborate carving were favorite occupations of the Mexicans, as well as of their forefathers, or the races, which preceded them. The famous Stone of Sacrifice, the Calendar of Montezuma, and the hideous idol Teoyamique, all still preserved, attest the grotesqueness and elaborate fancy of their designs. The latter image, as described by a traveler, “is hewn out of one solid block of basalt, nine feet high. Its outlines give an idea of a deformed human figure, uniting all that is terrible in the tiger and rattlesnake. Instead of arms, it is supplied with two large serpents, and its drapery is composed of wreathed snakes, interwoven in the most disgusting manner, and the sides terminating in the wings of a vulture. Its feet are those of a tiger, and between them lies the head of another rattle-snake, which seems descending from the body of the idol. For decorations, it has a large necklace composed of human hearts, hands, and skulls, and it has evidently been painted originally in natural colors.” Other figures of the deified rattlesnake have been discovered.

Great skill existed in the art of pottery, and many vessels of exquisite design and finish have been disinterred.

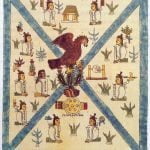

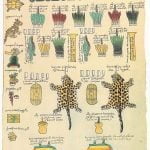

The hieroglyphical paintings and manuscripts of the Mexicans were, with few exceptions, destroyed by their fanatical conquerors. Some choice specimens, however, still exist; principally exhibiting the migrations of the Aztecs, their wars, their religious ceremonies, and the genealogy of their sovereigns. Almanacs and other calendars of an astronomical nature have been preserved. The material of the manuscript consists of the skins of animals, or of a kind of vegetable paper, formed in a manner similar to the Egyptian papyrus.

Of the numerous cities and temples whose remains are so abundant, many were, doubtless, erected by the Aztec people, whom Cortez found so numerous and flourishing, or by their immediate ancestors. Others were probably constructed at a remote age, and by a people who had at an early period migrated to these regions. A certain resemblance, however, appears to pervade them all. The presence of enormous pyramids and quadrangles, the peculiar construction of causeways and aqueducts, and the great similarity in mythological representation, appear to indicate that their founders were originally of a common stock, and all of certain national prepossessions.