As stated in Part Three, the Stratum Unlimited, LLC report in 2001 (Other Missing Stone Archaeological Sites) virtually ignored the Native American communities in northern Georgia. Almost all were contemporary with the occupation of the Track Rock Terraces. This omission was particularly inexcusable for the town sites that were adjacent to the two creeks, which flow off of Track Rock Gap, Town Creek and Arkaqua Creek. In 1930s and 1940s, archaeologist George Wauchope found evidence of long term occupancy at these sites that apparently began before the Track Rock terraces were constructed, and sometimes continued into the Federal Period. It should be understood, however, that since only two test pits were dug, the Track Rock terraces may be older than currently assumed.

The two large towns on the Etowah River in Georgia, known today as the Leake Mounds (100 BC-750 AD) Etowah Mounds (990 AD – 1585 AD,) culturally dominated the Lower Southeast for many centuries. It is 68 miles southwest of Track Rock Gap. The “logo” of the town of Etowah is on both the Track Rock petroglyphs and the Judaculla petroglyphs in North Carolina. The Judaculla petroglyphs are approximately the same distance northeast of Track Rock Gap as Etowah Mounds. However, the Judaculla petroglyphs were discussed extensively in the Stratum Unlimited, LLC report, while Etowah Mounds was ignored. As stated earlier, the main plaza at Etowah Mounds was supported by a six feet high retaining wall. A large complex of concentric fieldstone ellipses and other walls overlooked Etowah Mounds from Ladds Mountain.

Geospatial Relationship to Georgia Sites

In order to define the geospatial relationship between site 9UN367 and other contemporary sites in Georgia, all of the sites in a 75 mile radius were plotted on a GIS computer terrain model, utilizing latitude and longitude coordinates. The initial geospatial nodes were Track Rock Gap (Union County, GA) – Nottely Mounds (Union County, GA) – the peak of Brasstown Bald Mountain (Union & Towns County, GA) – Hightower Mounds (Towns County, GA) – Etowah Mounds and the Ladds Mountain stone observatory (Bartow County, GA) – Fort Mountain (Murray County, GA) – Fort Mountain (Union County, GA) – Aleck Mountain Stone Enclosure (Habersham County, GA) – the Nacoochee and Kenimer Mounds (White County, GA) – Dillard Mound Cluster (Rabun County, GA) – and the Summerour Mounds (Forsyth County, GA.) The GIS software drew lines between the nodes.

What immediately appeared was a triangular grid system that had the top of the mountain above Track Rock Gap and the peak of Brasstown Mountain as its benchmarks. Something even more remarkable appeared. Isosceles triangles were formed by the vectors between Track Rock Gap and Etowah Mounds, and Track Rock Gap and the Aleck Mountain stone enclosure. Their angles were approximately the azimuths of the Winter Solstice Sunset and Winter Solstice Sunrise respectively. The Nacoochee Mound aligned with the Winter Solstice Sunrise from the peak of Brasstown Bald Mountain.

There were also azimuth correlations for the Summer Solstice. Murray County, Georgia’s Fort Mountain was due west of Track Rock Gap. A town site in the Nottely River Valley (9UN1) and the stone structures on Mincie Mountain in Lumpkin County, GA were due south of Track Rock Gap. The Nacoochee Mound in the Nacoochee Valley was due east of the Mincie Mountain complex. The Kenimer Mound in the Nacoochee Valley was due north of Ocmulgee National Monument in Macon, GA – 128 miles to the south.

Perhaps the biggest surprise was the geospatial relationships of Track Rock Gap and Etowah Mounds to other regional centers during the period between 1000 AD and 1600 AD. If one extends the Winter Solstice Sunrise vector southeastward from Track Rock Gap and Aleck Mountain, it eventually passes over the Irene Mound Complex in Savannah, GA. That is 256 miles away! Extending the Summer Solstice sunrise vector eastward from Etowah Mounds eventually passes over the site of the Rembert Mound Complex near Elberton, GA. There are two known location of large spiral mounds in the United States, Ocmulgee National Monument near Macon, GA and Rembert Mounds near Elberton, GA.

The most powerful indigenous polity ever to exist north of Mexico began developing along the tributaries of the Coosa River in northwest Georgia around 1300 AD. Perhaps, it is an unrelated coincidence, but the capital of the Province of Kusa was aligned with the azimuth vector of the Equinox Sunset from Track Rock Gap. The Dillard Mound in extreme northeastern Georgia (Rabun County) was due east of the peak of Brasstown Bald Mountain.

There was a chain of towns along the Etowah River, dating back to around 750-800 AD that were on the important trade route between the shoals of the Etowah at Etowah Mounds and the Little Tennessee River at the confluence of the Little Tennessee with the Tuckasegee and Oconaluftee Rivers. Most of the towns along this trail did not seem to be aligned with the solar azimuth of Brasstown Bald or Track Rock Gap.

Geospatial Relationship to North Carolina Sites

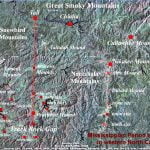

Known Mississippian Period sites in western North Carolina were also plotted onto a GIS base map. These sites included the Brasstown Mound (Cherokee County, NC) – Peachtree Mound (Cherokee County, NC) – former location of the Murphy Mound (Cherokee County, NC) – Quanasee town site near Hayesville, NC (Clay County, NC) – Tamatla and Andrews Mounds (Cherokee County, NC) – Tallulah Mounds (Graham County, NC) – Talasee town site (Graham County, NC) – Chiaha Island town site (Swain County, NC) – Kituwah Mound & town site (Swain County, NC) – Cullowhee Mounds & town site ( Jackson County, NC) – Nikasee Mound (Macon County, NC) and Otto Mounds & town site (Macon County, NC.) The computer software interconnected the nodes that represented these sites.

Only a few of the North Carolina mound sites seemed to be in a solar azimuth relationship with either Track Rock Gap or the peak of Brasstown Bald Mountain. Only the Peachtree Mound, Andrews Mound and Tallasee Island town site seemed to align to a north vector from Track Rock Gap. The large multiple mound town site and perhaps the Judiculla Petroglyph Boulder seemed to align to the angle of the Winter Solstice Sunset. Not shown on the map within this article is an alignment between the peak of Brasstown Bald Mountain and Hiwassee Island, Tennessee.

It is interesting that the vector between the peaks of Brasstown Bald Mountain and Mount Mitchell in North Carolina is the azimuth of the Winter Solstice sunset. This is obviously coincidence since both mountains were the creation of natural forces, not manmade structures.

Creation of Triangular Grid

Currently, there is no explanation of how the indigenous people of the Southeast were able to survey out a precise grid based on the solar azimuth over such long distances. Their surveying system was obviously based on the sun, but the question still remains of how they were able to lay out straight traverse lines over mountains, rivers and valleys. The vectors all align with the solar azimuth, not those we use today, which are based on magnetic north and south. This would have been an impossible task for Anglo-American surveyors until the late 1800’s, when long distance railroad construction spawned advances in surveying equipment and trigonometry.

To understand the technological feat accomplished by these American Indian surveyors from a thousand years ago, one should consider the level of surveying technology when Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic in 1492. Reasonably reliable techniques for calculating latitude only developed in the decades immediately prior to Columbus’s voyage. This is when the Roman Catholic Church finally admitted that the earth was round. Even to attempt calculation of latitude prior to then would have been an act of heresy, punishable by being burned at the stake.

The concept of a magnetic compass arrived in Western Europe from China in the 1100’s AD. It appears in the Moslem world about 150 years later. However, the mariner’s dry compass was invented by Europeans around 1300 AD. The magnetic compass enabled navigators to know the relationship between a ship and the magnetic north pole. This was different that the solar north pole used by Native American surveyors. Nevertheless, the compass still did not tell navigators how far they had traveled east or west on a given day. The mathematics for such calculations were developing in 1492, but Columbus’s estimation of distance traveled was inaccurate. Accurate calculation of longitude did not occur in Europe until the 1600s.

For American Indian surveyors to stake out a grid over distances, sometimes of over 100 miles, meant that they had the mathematical ability to calculate their equivalent of latitude and longitude. Apparently, they also had the equivalent of trigonometry to calculate heights at distance. The precision of GIS-based computer technology makes their achievements irrefutable. However, they do not give a hint of how Native American surveyors accomplished this feat without transits or calculators. It remains a mystery.