The following are various forms of dances described by the Choctaw members of Bayou Lacomb.

1. Nanena hitkla (Man dance)

All lock arms and form a ring; all sing and the ring revolves rapidly. No one remains in the ring.

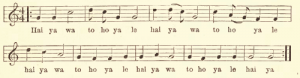

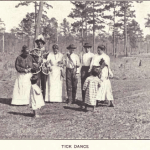

2. Shatene hitkla (Tick dance)

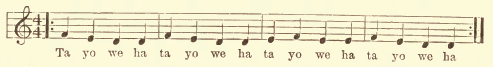

The dancers lock arms and form in straight lines. First they move forward two or three steps, then backward, but they gradually advance. When they take the forward step they stamp with the right foot, as if crushing ticks on the ground, at the same time looking down, supposedly at the doomed insects. During the dance all sing with many repetitions the song here given, the words of which have no special meaning.

3. Kwishco kitkla (Drunken Man Dance)

Two lines facing each other are formed by the dancers, who lock arms. The lines slowly approach then move backward, and then again approach. All endeavor to keep step, and during the dance all sing. The song, which is repeated many times, is evidently a favorite with the Choctaw at Bayou Lacomb.

4. Tinsanale hikla

In this dance two persons, facing, clasp each other’s hands. Many couples in this position form a ring. One man remains in the center to keep time for the singing and the circle of dancers revolves around him. The Indians say many persons are required in order to perform this dance properly.

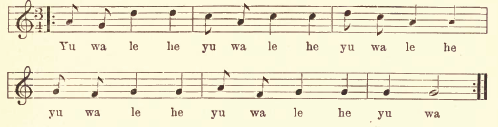

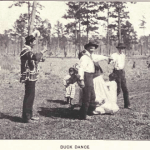

5. Fuchuse hitkla (Duck dance)

Partners are required in this dance also; they form two lines, facing. The peculiar feature is that two partners pass under the arms of another couple, as shown in plate 21. The dancers endeavor to imitate the motion of a duck in walking, hence the name of the dance.

6. Hitkla Falama (Dance Go-and-come)

All lock arms and the line moves sideways, first in one direction, then in the opposite, but never backward or forward. If there are too many dancers for a single line, additional lines are formed.

7. Siente hitkla (Snake dance)

Of the seven dances this appears to have been the great favorite as it was also the last., The dancers form in a single line, either grasping hands or each holding on to the shoulder of the dancer immediately in front. First come the men, then the women, and lastly the boys and girls, if any are to dance. The first man in the line is naturally the leader; he moves along in a serpentine course, all following. Gradually he leads the dancers around and around until finally the line becomes coiled, in form resembling a snake. Soon the coil becomes so close it is impossible to move farther; thereupon the participants release their hold on one another and cease dancing. As will be seen, the song belonging to this dance is very simple, but it is repeated many, many times, being sung during the entire time consumed by the dance, said to he an hour or more. This dance is shown in plate 22. The snake dance closed the ceremony.

The Bayou Lacomb Choctaw always danced at night, never during daylight hours, the snake dance, the last of the seven, ending at dawn. This agrees with the statement made by Bossu just one and a half centuries ago that “nearly all the gatherings of the Chactas take place at night.” 1

Neither the men nor the women of this branch of the tribe appear to know of any special dances, although it is highly probable that in former years distinct ceremonies were enacted on particular occasions.

Until a few years ago there were several hundred Choctaw living in the vicinity of Bayou Lacomb within a radius of a few miles. Their dance ground was in the pine woods a short distance north of the place where the few remaining members of the tribe now dwell. There they would gather and with many fires blazing would dance throughout the night. No whites ever were permitted to witness the dance. It is said that if the Indians suspected a white man was watching them they would extinguish the fires once and remain in darkness. During the dances one man acted as leader. He held two short sticks, hitting one on the other to keep time for the singing, as shown in the Snake Dance.

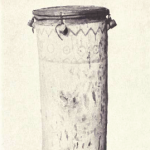

The only musical instrument known to the Choctaw of Bayou Lacomb is the drum (the’ba), a good example of which is represented in the following image.

This is 30 inches in height and 15 inches in diameter. It is made of a section of a black gum tree; the cylinder wall is less than 2 inches in thickness. The head consists of a piece of untanned goat skin. The skin is stretched over the open end, while wet and pliable, and is passed around a hoop made of hickory about half an inch thick. A similar hoop is placed above the first. To the second hoop are attached four narrow strips of rawhide, each of which is fastened to a peg passing diagonally through the wall of the drum. To tighten the head of the drum it is necessary merely to drive the peg farther in. In this respect, as well as in general form, the drum resembles a specimen from Virginia in the British Museum 2 ,” as well as the drum even now used on the west coast of Africa. It is not possible to say whether this instrument is a purely American form or whether it shows the influence of the negro.

Citations:

- Nouveaux voyages aux Indes occidentales, Ii, 104, Paris, 1768 [written in 1759].[

]

- The Sloane Collection in the British Museum, American Anthropologist, n. s., viii, no. 4, 671-685, 1906.[

]