Typewritten records prepared by the Federal Writers’ Project 1936-1938. 1 Assembled by the Library of Congress Project work projects administration for the District of Columbia sponsored by the Library of Congress.

When comparing these life stories to the works of formal historians, social scientists, novelists, slave autobiographies, and contemporary records of abolitionists and plantation owners, it’s clear that these accounts, recorded in the narrators’ own words as much as possible, offer an invaluable collection of indirect evidence. This information is indispensable for scholars and writers focusing on the South, particularly social psychologists and cultural anthropologists. For the first and perhaps only time, numerous surviving slaves (many of whom have since passed away) have been given the opportunity to share their experiences in their own words. Despite inevitable limitations—such as the bias and fallibility of both interviewees and interviewers, leading questions, unrefined techniques, and a lack of proper controls—this chronicle remains the most genuine and vivid source for understanding the lives and thoughts of thousands of slaves, their relationships with each other, their masters and mistresses, overseers, and attitudes towards various aspects of life in the South.

These accounts are part of folk history, drawn from the memories and words of those who lived through or witnessed these events. They combine group and individual experiences, observations, hearsay, and tradition. The narrators provide insight into not only what they saw, felt, and thought at the time, but also their reflections on slavery since then. To the existing white narrative of slavery, the slaves’ own folklore and stories must be added. The patterns revealed are diverse, ranging from regional and occupational differences to varying degrees of kindness and cruelty exhibited by masters or mistresses, and even the influence of various racial backgrounds (including Creole and Indian).

These narratives are also an integral part of folk literature, abundant not only in folk songs, stories, and speech but also in humor and poetry. They display an array of dialects, tones, and styles, often enriching the reader with earthy imagery, expressive phrases, and attentive details. In their unintentional artistry, as seen in numerous compelling short stories, they contribute to the realistic writing of the Black experience. Despite any surface inconsistencies and exaggerations, their core truth and humanity surpass and complement both history and literature.

About WPA Slave Narratives

Slave narratives are stories of surviving slaves told in their own words and ways. Unique, colorful, and authentic, these slave narratives provide a look at the culture of the South during slavery which heretofore had not been told.

Table of Contents:

- 1850 Slave Bill of Sale

- Biography of Alfred Richardson

- Boyd County, Kentucky

- Buying and Selling Slaves

- Casey Co., Ky

- Cemetery Hill

- Clark Co., Ky

- Coal Mine Slaves

- Hoo-Dooism

- Hopkins Co., Ky

- Kentucky Superstitions

- Knox Co., Ky

- Last Wolf

- List of Slave Owners

- Montgomery Co., Ky

- Myth at Uncle Tom’s Cabin

- Negro Folk Songs

- Negro Holiness Meetings

- Recreations of Slaves

- Slave Trade Pricing

- Superstitions of Negro Race

- The Missing Man

- Underground Railroad

- Will of Nancy Austin

Slave Narratives

The collection featured in this online anthology has been transcribed directly from interviews conducted by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) writers in the late 1930s. The narratives present reading challenges due to the use of dialect and inconsistent transcription techniques. To better understand the spoken language, readers might find it helpful to read the passages aloud, imagining the sounds of the words as they were spoken.

A close reading of these narratives reveals subtle details and layers of emotion that may not be immediately apparent. The narratives often contain ambiguities and complexities that are worth exploring. For instance, when Emma Crockett recounts her experiences with whippings, she speaks vaguely, perhaps influenced by her advanced age, failing memory, or the proximity of descendants of those who once held power over her. Her reserve in naming specific perpetrators or detailing the brutalities might reflect a mix of caution, forgiveness, or a resigned acceptance of her past.

These narratives also exhibit lapses, inconsistencies, and frequent repetitions, reflective of the advanced age of the interviewees and the structured nature of the interview questions, which focused on topics like labor, diet, marriage, and punishment. Some interviewers adhered strictly to these prompts, while others allowed the conversations to flow more freely.

Modern readers will also encounter, in some instances, a patronizing tone from the interviewers and an apparent deference from the interview subjects. It’s crucial to recognize that these interviews were conducted in the racially charged atmosphere of the Jim Crow South, nearly sixty years after the end of slavery. The language and attitudes reflect not only the individual experiences of former slaves but also the pervasive racial ideologies of the time.

These narratives are listed alphabetically by their first name. If you are looking for a particular surname, then perform a search with your browser on this page or use our search at the top of the page.

- Slave Narrative of “Aunt” Nina Scott

- Slave Narrative of “Father” Charles Coates

- Slave Narrative of “Parson” Rezin Williams

- Slave Narrative of “Prophet” John Henry Kemp

- Slave Narrative of “Uncle” Bill Young

- Slave Narrative of Acemey Wofford

- Slave Narrative of Acie Thomas

- Slave Narrative of Adah I. Suggs

- Slave Narrative of Addy Gill

- Slave Narrative of Adeline Crump

- Slave Narrative of Adeline R. Lennox

- Slave Narrative of Al Rosboro

- Slave Narrative of Alec Bostwick

- Slave Narrative of Aleck Woodward

- Slave Narrative of Alex & Elizabeth Smith

- Slave Narrative of Alex Huggins

- Slave Narrative of Alex Woodson

- Slave Narrative of Alexander Robertson

- Slave Narrative of Alexander Scaife

- Slave Narrative of Alfred Sligh

- Slave Narrative of Alfred Smith

- Slave Narrative of Alice Alexander

- Slave Narrative of Alice Battle

- Slave Narrative of Alice Baugh

- Slave Narrative of Alice Biggs

- Slave Narrative of Alice Bradley

- Slave Narrative of Alice Douglass

- Slave Narrative of Alice Lewis

- Slave Narrative of Allen V. Manning

- Slave Narrative of Alonzo Haywood

- Slave Narrative of Amanda E. Samuels

- Slave Narrative of Amanda McCray

- Slave Narrative of Amanda Oliver

- Slave Narrative of Ambrose Douglass

- Slave Narrative of Amelia Jones

- Slave Narrative of America Morgan

- Slave Narrative of Amsy O. Alexander

- Slave Narrative of Amy E. Patterson

- Slave Narrative of Analiza Foster

- Slave Narrative of Anderson Furr

- Slave Narrative of Anderson Whitted

- Slave Narrative of Andrew Boone

- Slave Narrative of Andrew Moss

- Slave Narrative of Andrew Simms

- Slave Narrative of Andrew Simms

- Slave Narrative of Andy Odell

- Slave Narrative of Angeline Lester

- Slave Narrative of Angie Boyce

- Slave Narrative of Ann Gudgel

- Slave Narrative of Ann Matthews

- Slave Narrative of Anna Baker

- Slave Narrative of Anna Scott

- Slave Narrative of Anna Smith

- Slave Narrative of Anne Rice

- Slave Narrative of Annie B. Boyd

- Slave Narrative of Annie Beck

- Slave Narrative of Annie Gail

- Slave Narrative of Annie Groves Scott

- Slave Narrative of Annie Hawkins

- Slave Narrative of Annie Morgan

- Slave Narrative of Annie Trip

- Slave Narrative of Annie Young Henson

- Slave Narrative of Anthony Dawson

- Slave Narrative of Arnold Gragston

- Slave Narrative of Arrie Binns

- Slave Narrative of Aunt Adeline

- Slave Narrative of Aunt Betty Cofer

- Slave Narrative of Aunt Harriet Mason

- Slave Narrative of Aunt Laura Bell

- Slave Narrative of Aunt Mary Williams

- Slave Narrative of Aunt Mollie Moss

- Slave Narrative of Banana Williams

- Slave Narrative of Barbara Haywood

- Slave Narrative of Barney Stone

- Slave Narrative of Beatrice Black

- Slave Narrative of Belle Robinson

- Slave Narrative of Ben Brown

- Slave Narrative of Benjamin Russell

- Slave Narrative of Benny Dillard

- Slave Narrative of Berry Clay

- Slave Narrative of Berry Smith

- Slave Narrative of Bert Luster

- Slave Narrative of Bert Mayfield

- Slave Narrative of Bettie Suber

- Slave Narrative of Betty Foreman Chessier

- Slave Narrative of Betty Guwn

- Slave Narrative of Betty Jones

- Slave Narrative of Betty Robertson

- Slave Narrative of Bill Austin

- Slave Narrative of Bill Crump

- Slave Narrative of Bill Williams

- Slave Narrative of Billy Slaughter

- Slave Narrative of Blount Baker

- Slave Narrative of Bob Benford

- Slave Narrative of Bob Maynard

- Slave Narrative of Bob Young

- Slave Narrative of Bolden Hall

- Slave Narrative of Boston Blackwell

- Slave Narrative of Callie Bracey

- Slave Narrative of Callie Elder

- Slave Narrative of Candus Richardson

- Slave Narrative of Carl Boone

- Slave Narrative of Caroline Hammond

- Slave Narrative of Carrie Bradley Logan Bennett

- Slave Narrative of Carrie Nancy Fryer

- Slave Narrative of Catherine Slim

- Slave Narrative of Cecelia Chappel

- Slave Narrative of Celia Henderson

- Slave Narrative of Chaney Hews

- Slave Narrative of Chaney Mayer

- Slave Narrative of Chaney Richardson

- Slave Narrative of Charity Austin

- Slave Narrative of Charity Anderson

- Slave Narrative of Charles Anderson

- Slave Narrative of Charles Coles

- Slave Narrative of Charles H. Anderson

- Slave Narrative of Charles Lee Dalton

- Slave Narrative of Charles W. Dickens

- Slave Narrative of Charles Willis

- Slave Narrative of Charley Roberts

- Slave Narrative of Charley Watson

- Slave Narrative of Charley Williams

- Slave Narrative of Charlie Barbour

- Slave Narrative of Charlie Crump

- Slave Narrative of Charlie Davenport

- Slave Narrative of Charlie H. Hunter

- Slave Narrative of Charlie Moses

- Slave Narrative of Charlie Richmond

- Slave Narrative of Charlie Robinson

- Slave Narrative of Charlotte Martin

- Slave Narrative of Christine Mitchell

- Slave Narrative of Cindy Kinsey

- Slave Narrative of Clara C. Young

- Slave Narrative of Claude Augusta Wilson

- Slave Narrative of Clay Bobbit

- Slave Narrative of Clayborn Gantling

- Slave Narrative of Clayton Holbert

- Slave Narrative of Cora Armstrong

- Slave Narrative of Cora Torian

- Slave Narrative of Cornelia Andrews

- Slave Narrative of Cy Hart

- Slave Narrative of Cyrus Bellus

- Slave Narrative of Dan Bogie

- Slave Narrative of Dan Smith

- Slave Narrative of Dan Thomas

- Slave Narrative of Daniel Waring

- Slave Narrative of Daniel William Lucas

- Slave Narrative of Daphney Wright

- Slave Narrative of Dave Taylor

- Slave Narrative of David A. Hall

- Slave Narrative of David Lee

- Slave Narrative of Delia Thompson

- Slave Narrative of Della Bess Hilyard

- Slave Narrative of Della Briscoe

- Slave Narrative of Della Fountain

- Slave Narrative of Dennis Simms

- Slave Narrative of Diana Alexander

- Slave Narrative of Dina Beard

- Slave Narrative of Doc Daniel Dowdy

- Slave Narrative of Doc Edwards

- Slave Narrative of Dora Franks

- Slave Narrative of Dorcas Griffeth

- Slave Narrative of Douglas Dorsey

- Slave Narrative of Douglas Parish

- Slave Narrative of Duncan Gaines

- Slave Narrative of Easter Brown

- Slave Narrative of Easter Sudie Campbell

- Slave Narrative of Easter Wells

- Slave Narrative of Ed Allen

- Slave Narrative of Edd Shirley

- Slave Narrative of Edna Boysaw

- Slave Narrative of Edward Lycurgas

- Slave Narrative of Elbert Hunter

- Slave Narrative of Eliza Evans

- Slave Narrative of Eliza Scantling

- Slave Narrative of Eliza Whitmire

- Slave Narrative of Elizabeth Alexander

- Slave Narrative of Ellen Cave

- Slave Narrative of Ellen Claibourn

- Slave Narrative of Ellen Renwick

- Slave Narrative of Ellen Swindler

- Slave Narrative of Ellis Ken Kannon

- Slave Narrative of Elphas P. Hylton

- Slave Narrative of Elsie Pryor

- Slave Narrative of Emma Barr

- Slave Narrative of Emma Blalock

- Slave Narrative of Emma Grisham

- Slave Narrative of Emma Knight

- Slave Narrative of Emmett Beal

- Slave Narrative of Emoline Satterwhite

- Slave Narrative of Emoline Wilson

- Slave Narrative of Emoline Wilson

- Slave Narrative of Enoch Beel

- Slave Narrative of Essex Henry

- Slave Narrative of Esther Hudespeth

- Slave Narrative of Eustace Hodges

- Slave Narrative of Eva Strayhorn

- Slave Narrative of Fannie Alexander

- Slave Narrative of Fannie Dunn

- Slave Narrative of Fannie McCay

- Slave Narrative of Fanny Cannady

- Slave Narrative of Fanny Smith Hodges

- Slave Narrative of Fleming Clark

- Slave Narrative of Florida Clayton

- Slave Narrative of Frances Batson

- Slave Narrative of Francis Bridges

- Slave Narrative of Frank Bates

- Slave Narrative of Frank Berry

- Slave Narrative of Frank Cannon

- Slave Narrative of Frank Freeman

- Slave Narrative of Frank Range

- Slave Narrative of Frankie Goole

- Slave Narrative of Gabe Emanuel

- Slave Narrative of George Benson

- Slave Narrative of George Brooks

- Slave Narrative of George Conrad, Jr.

- Slave Narrative of George Dorsey

- Slave Narrative of George Eason

- Slave Narrative of George Eatman

- Slave Narrative of George Fortman

- Slave Narrative of George Henderson

- Slave Narrative of George Jackson

- Slave Narrative of George Jones

- Slave Narrative of George Kye

- Slave Narrative of George Morrison

- Slave Narrative of George Pretty

- Slave Narrative of George Scruggs

- Slave Narrative of George Taylor Burns

- Slave Narrative of George Thompson

- Slave Narrative of George W. Arnold

- Slave Narrative of George W. Harris

- Slave Narrative of George Washington Buckner

- Slave Narrative of George Woods (Wood)

- Slave Narrative of Georgia Baker

- Slave Narrative of Georgianna Foster

- Slave Narrative of Gus Clark

- Slave Narrative of H. H. Edmunds

- Slave Narrative of Hal Hutson

- Slave Narrative of Hamp Kennedy

- Slave Narrative of Hannah Austin

- Slave Narrative of Hannah Crasson

- Slave Narrative of Hannah McFarland

- Slave Narrative of Harriet Ann Daves

- Slave Narrative of Harriet Cheatam

- Slave Narrative of Harriet Mason

- Slave Narrative of Harriett Gresham

- Slave Narrative of Harriett Robinson

- Slave Narrative of Hattie Thomas

- Slave Narrative of Hecter Hamilton

- Slave Narrative of Hector Smith

- Slave Narrative of Hector Smith

- Slave Narrative of Henri Necaise

- Slave Narrative of Henrietta Jackson

- Slave Narrative of Henry Anthony

- Slave Narrative of Henry Banner

- Slave Narrative of Henry Blake

- Slave Narrative of Henry Bland

- Slave Narrative of Henry Clay Moorman

- Slave Narrative of Henry F. Pyles

- Slave Narrative of Henry Maxwell

- Slave Narrative of Henry Ryan

- Slave Narrative of Henry Ryan

- Slave Narrative of Herndon Bogan

- Slave Narrative of Hula Williams

- Slave Narrative of Ida Adkins

- Slave Narrative of Ida Henry

- Slave Narrative of Irene Coates

- Slave Narrative of Isaac Adams

- Slave Narrative of Isaac Stier

- Slave Narrative of Isabell Henderson

- Slave Narrative of Isom Roberts

- Slave Narrative of J. H. Beckwith

- Slave Narrative of J. W. Stinnett

- Slave Narrative of Jack Atkinson

- Slave Narrative of Jack Simms

- Slave Narrative of James Baker

- Slave Narrative of James Bertrand

- Slave Narrative of James Bolton

- Slave Narrative of James Calhart James

- Slave Narrative of James Campbell

- Slave Narrative of James Childress

- Slave Narrative of James Cornelius

- Slave Narrative of James Lucas

- Slave Narrative of James Singleton

- Slave Narrative of James Southall

- Slave Narrative of James V. Deane

- Slave Narrative of James Wiggins

- Slave Narrative of Jane Arrington

- Slave Narrative of Jane Birch

- Slave Narrative of Jane Montgomery

- Slave Narrative of Jane Smith

- Slave Narrative of Jane Sutton

- Slave Narrative of Jane Wilson

- Slave Narrative of Jasper Battle

- Slave Narrative of Jeff Bailey

- Slave Narrative of Jennie Colder

- Slave Narrative of Jennie Small

- Slave Narrative of Jenny Greer

- Slave Narrative of Jenny McKee

- Slave Narrative of Jennylin Dunn

- Slave Narrative of Jerry Davis

- Slave Narrative of Jerry Hinton

- Slave Narrative of Jesse Rice

- Slave Narrative of Jesse Williams

- Slave Narrative of Jessie Rowell

- Slave Narrative of Jim Allen

- Slave Narrative of Jim Taylor

- Slave Narrative of Jim Threat

- Slave Narrative of Joana Owens

- Slave Narrative of Joanna Draper

- Slave Narrative of Joe High

- Slave Narrative of Joe Robinson

- Slave Narrative of Joe Rutherford

- Slave Narrative of John Anderson

- Slave Narrative of John Beckwith

- Slave Narrative of John Brown

- Slave Narrative of John C. Bectom

- Slave Narrative of John Cameron

- Slave Narrative of John Coggin

- Slave Narrative of John Cole

- Slave Narrative of John Daniels

- Slave Narrative of John Eubanks

- Slave Narrative of John Eubanks & Family

- Slave Narrative of John Evans

- Slave Narrative of John Fields

- Slave Narrative of John H. Gibson

- Slave Narrative of John Rudd

- Slave Narrative of John W. Fields

- Slave Narrative of John W. H. Barnett

- Slave Narrative of John W. Matheus

- Slave Narrative of John White

- Slave Narrative of Johnson Thompson

- Slave Narrative of Joseph Anderson

- Slave Narrative of Joseph Leonidas Star

- Slave Narrative of Joseph Mosley

- Slave Narrative of Joseph Samuel Badgett

- Slave Narrative of Joseph William Carter

- Slave Narrative of Josephine Ames

- Slave Narrative of Josephine Anderson

- Slave Narrative of Josephine Ann Barnett

- Slave Narrative of Josephine Stewart

- Slave Narrative of Julia Bowman

- Slave Narrative of Julia Brown (Aunt Sally)

- Slave Narrative of Julia Bunch

- Slave Narrative of Julia Casey

- Slave Narrative of Julia Cole

- Slave Narrative of Julia Crenshaw

- Slave Narrative of Julia King

- Slave Narrative of Julia Williams

- Slave Narrative of Julia Williams

- Slave Narrative of Julia Woodberry

- Slave Narrative of Julia Woodberry

- Slave Narrative of Julia Woodberry

- Slave Narrative of Julia Woodberry

- Slave Narrative of Kate Billingsby

- Slave Narrative of Katie Arbery

- Slave Narrative of Katie Rowe

- Slave Narrative of Katie Sutton

- Slave Narrative of Kato Benton

- Slave Narrative of Kisey McKimm

- Slave Narrative of Kitty Hill

- Slave Narrative of Kizzie Colquitt

- Slave Narrative of Laura Abromsom

- Slave Narrative of Laura Ramsey Parker

- Slave Narrative of Lewis Bonner

- Slave Narrative of Lewis Favor

- Slave Narrative of Lila Rutherford

- Slave Narrative of Lindsey Faucette

- Slave Narrative of Lindsey Moore

- Slave Narrative of Liza Smith

- Slave Narrative of Lizzie Baker

- Slave Narrative of Lizzie Barnett

- Slave Narrative of Lizzie Farmer

- Slave Narrative of Lizzie Johnson

- Slave Narrative of Lou Smith

- Slave Narrative of Louisa Adams

- Slave Narrative of Lucinda Davis

- Slave Narrative of Lucinda Vann

- Slave Narrative of Lucindy Allison

- Slave Narrative of Lucretia Alexander

- Slave Narrative of Lucy Ann Dunn

- Slave Narrative of Lucy Brooks

- Slave Narrative of Lucy Brown

- Slave Narrative of Luke Towns

- Slave Narrative of Mack Mullen

- Slave Narrative of Mack Taylor

- Slave Narrative of Mama Duck

- Slave Narrative of Mamie Riley

- Slave Narrative of Manda Walker

- Slave Narrative of Mandy Billings

- Slave Narrative of Mandy Cooper

- Slave Narrative of Mandy Coverson

- Slave Narrative of Mandy Gibson

- Slave Narrative of Margaret E. Dickens

- Slave Narrative of Margaret White

- Slave Narrative of Margrett Nickerson

- Slave Narrative of Mariah Callaway

- Slave Narrative of Marshal Butler

- Slave Narrative of Marshall Mack

- Slave Narrative of Martha Adeline Hinton

- Slave Narrative of Martha Allen

- Slave Narrative of Martha Colquitt

- Slave Narrative of Martha Everette

- Slave Narrative of Martha J. Jones

- Slave Narrative of Martha King

- Slave Narrative of Martha Richardson

- Slave Narrative of Mary Anderson

- Slave Narrative of Mary Anngady

- Slave Narrative of Mary B. Dempsey

- Slave Narrative of Mary Barbour

- Slave Narrative of Mary Colbert

- Slave Narrative of Mary Crane

- Slave Narrative of Mary Ferguson

- Slave Narrative of Mary Frances Webb

- Slave Narrative of Mary Grayson

- Slave Narrative of Mary Lindsay

- Slave Narrative of Mary Minus Biddie

- Slave Narrative of Mary Moriah Anne Susanna James

- Slave Narrative of Mary Raines

- Slave Narrative of Mary Scott

- Slave Narrative of Mary Smith

- Slave Narrative of Mary Veals

- Slave Narrative of Mary Veals

- Slave Narrative of Mary Wallace Bowe

- Slave Narrative of Mary Woodward

- Slave Narrative of Mary Wooldridge

- Slave Narrative of Mary Wright

- Slave Narrative of Matilda Bass

- Slave Narrative of Matilda Brooks

- Slave Narrative of Matilda Poe

- Slave Narrative of Matthew Hume

- Slave Narrative of Mattie Curtis

- Slave Narrative of Mattie Hariman

- Slave Narrative of Measy Hudson

- Slave Narrative of Melissa (Lowe) Barden

- Slave Narrative of Menellis Gassaway

- Slave Narrative of Midge Burnett

- Slave Narrative of Millie Sampson

- Slave Narrative of Millie Simpkins

- Slave Narrative of Milly Henry

- Slave Narrative of Milton Starr

- Slave Narrative of Miss Adeline Blakeley

- Slave Narrative of Mittie Blakeley

- Slave Narrative of Mollie Williams

- Slave Narrative of Mom Genia Woodberry

- Slave Narrative of Mom Jessie Sparrow

- Slave Narrative of Mom Jessie Sparrow

- Slave Narrative of Mom Jessie Sparrow

- Slave Narrative of Mom Jessie Sparrow

- Slave Narrative of Morgan Scurry

- Slave Narrative of Morris Hillyer

- Slave Narrative of Morris Sheppard

- Slave Narrative of Mose Banks

- Slave Narrative of Mose Davis

- Slave Narrative of Moses Smith

- Slave Narrative of Mr. McIntosh

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. C. Hood

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. Celestia Avery

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. Duncan

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. Emmaline Heard

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. Hannah Davidson

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. Heyburn

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. Hockaday

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. M. S. Fayman

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. Melissa (Lowe) Barden

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. Phoebe Bost

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. Preston

- Slave Narrative of Mrs. Sarah Byrd

- Slave Narrative of Naisy Reece

- Slave Narrative of Nan Stewart

- Slave Narrative of Nancy Boudry

- Slave Narrative of Nancy East

- Slave Narrative of Nancy Gardner

- Slave Narrative of Nancy Rogers Bean

- Slave Narrative of Nancy Washington

- Slave Narrative of Nancy Whallen

- Slave Narrative of Nannie Eaves

- Slave Narrative of Narcissus Young

- Slave Narrative of Nathan Jones

- Slave Narrative of Ned Thompson

- Slave Narrative of Ned Walker

- Slave Narrative of Neil Coker

- Slave Narrative of Nellie Johnson

- Slave Narrative of Nettie Henry

- Slave Narrative of Octavia George

- Slave Narrative of Ora M. Flagg

- Slave Narrative of Page Harris

- Slave Narrative of Parthena Rollins

- Slave Narrative of Patience Campbell

- Slave Narrative of Patsy Hyde

- Slave Narrative of Pauline Worth

- Slave Narrative of Perry Lewis

- Slave Narrative of Perry Sid Jemison

- Slave Narrative of Pet Franks

- Slave Narrative of Peter Bruner

- Slave Narrative of Phillip Johnson

- Slave Narrative of Phillip Rice

- Slave Narrative of Phoebe Banks

- Slave Narrative of Phyllis Petite

- Slave Narrative of Pierce Cody

- Slave Narrative of Polly Colbert

- Slave Narrative of Precilla Gray

- Slave Narrative of Prince Bee

- Slave Narrative of Prince Johnson

- Slave Narrative of Prince Smith

- Slave Narrative of Priscilla Mitchell

- Slave Narrative of R. B. Anderson

- Slave Narrative of R. C. Smith

- Slave Narrative of Rachel Adams

- Slave Narrative of Rachel Gaines

- Slave Narrative of Randall Lee

- Slave Narrative of Rebecca Hooks

- Slave Narrative of Red Richardson

- Slave Narrative of Reuben Rosborough

- Slave Narrative of Rev. Eli Boyd

- Slave Narrative of Rev. John Moore

- Slave Narrative of Rev. John R. Cox

- Slave Narrative of Rev. Silas Jackson

- Slave Narrative of Rev. Squires Jackson

- Slave Narrative of Rev. W. B. Allen

- Slave Narrative of Rev. Wamble

- Slave Narrative of Reverend Squire Dowd

- Slave Narrative of Reverend Williams

- Slave Narrative of Rias Body

- Slave Narrative of Richard Macks

- Slave Narrative of Richard Miller

- Slave Narrative of Richard Toler

- Slave Narrative of Rivana Boynton

- Slave Narrative of Robert Barr

- Slave Narrative of Robert Falls

- Slave Narrative of Robert Glenn

- Slave Narrative of Robert Hinton

- Slave Narrative of Robert Howard

- Slave Narrative of Robert McKinley

- Slave Narrative of Robert R. Grinstead

- Slave Narrative of Robert Toatley

- Slave Narrative of Robert Williams

- Slave Narrative of Rosa Barber

- Slave Narrative of Rosa Starke

- Slave Narrative of Rosaline Rogers

- Slave Narrative of Rose Adway

- Slave Narrative of Salena Taswell

- Slave Narrative of Sallie Carder

- Slave Narrative of Sam and Louisa Everett

- Slave Narrative of Sam McAllum

- Slave Narrative of Sam Rawls

- Slave Narrative of Samuel Simeon Andrews

- Slave Narrative of Samuel Smalls

- Slave Narrative of Samuel Sutton

- Slave Narrative of Samuel Watson

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Anderson

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Anne Green

- Slave Narrative of Sarah C. Colbert

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Debro

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Gudger

- Slave Narrative of Sarah H. Locke

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Harris

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Harris

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Louise Augustus

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Mann

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Ross

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Wilson

- Slave Narrative of Sarah Woods Burke

- Slave Narrative of Scott Martin

- Slave Narrative of Scott Mitchell

- Slave Narrative of Selie Anderson

- Slave Narrative of Shack Thomas

- Slave Narrative of Silas Smith

- Slave Narrative of Sophia Word

- Slave Narrative of Sophie D. Belle

- Slave Narrative of Spencer Barnett

- Slave Narrative of Stephen McCray

- Slave Narrative of Susan Bledsoe

- Slave Narrative of Susan Castle

- Slave Narrative of Susan Dale Sanders

- Slave Narrative of Susan High

- Slave Narrative of Susan Snow

- Slave Narrative of Susie Riser

- Slave Narrative of Sweetie Ivery Wagoner

- Slave Narrative of Sylvia Watkins

- Slave Narrative of Taylor Gilbert

- Slave Narrative of Tempie Herndon Durham

- Slave Narrative of Tena White

- Slave Narrative of Thomas Ash

- Slave Narrative of Thomas Foote

- Slave Narrative of Thomas Hall

- Slave Narrative of Thomas Lewis

- Slave Narrative of Thomas McMillan

- Slave Narrative of Titus I. Bynes

- Slave Narrative of Tom Randall

- Slave Narrative of Tom Rosboro

- Slave Narrative of Tom W. Woods

- Slave Narrative of Tom Wilson

- Slave Narrative of Uncle Dave White

- Slave Narrative of Uncle Dave White

- Slave Narrative of Uncle David Blount

- Slave Narrative of Uncle Dick

- Slave Narrative of Uncle Ransom Simmons

- Slave Narrative of Uncle Sabe Rutledge

- Slave Narrative of Uncle Willis Williams

- Slave Narrative of Vera Roy Bobo

- Slave Narrative of Victoria Taylor Thompson

- Slave Narrative of Viney Baker

- Slave Narrative of W. A. Anderson

- Slave Narrative of W. B. Morgan

- Slave Narrative of W. Solomon Debnam

- Slave Narrative of Wade Glenn

- Slave Narrative of Walter Calloway

- Slave Narrative of Washington Allen

- Slave Narrative of Wayne Holliday

- Slave Narrative of Wes Woods

- Slave Narrative of Wiley Childress

- Slave Narrative of Will Oats

- Slave Narrative of William Curtis

- Slave Narrative of William George Hinton

- Slave Narrative of William Hutson

- Slave Narrative of William M. Quinn

- Slave Narrative of William Neightgen

- Slave Narrative of William Nelson

- Slave Narrative of William Rose

- Slave Narrative of William Sherman

- Slave Narrative of William W. Watson

- Slave Narrative of William Williams

- Slave Narrative of Willis Cofer

- Slave Narrative of Willis Cozart

- Slave Narrative of Willis Dukes

- Slave Narrative of Willis Williams

- Slave Narrative of Young Winston Davis

- Slave Narrative of Zeb Crowder

The present Library of Congress Project, under the sponsorship of the Library of Congress, is a unit of the Public Activities Program of the Community Service Programs of the Work Projects Administration for the District of Columbia. According to the Project Proposal (WPA Form 301), the purpose of the Project is to “collect, check, edit, index, and otherwise prepare for use WPA records, Professional and Service Projects.”

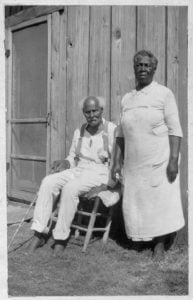

The Writers’ Unit of the Library of Congress Project processes material left over from or not needed for publication by the state Writers’ Projects. On file in the Washington office in August, 1939, was a large body of slave narratives, photographs of former slaves, interviews with white informants regarding slavery, transcripts of laws, advertisements, records of sale, transfer, and manumission of slaves, and other documents. As unpublished manuscripts of the Federal Writers’ Project these records passed into the hands of the Library of Congress Project for processing; and from them has been assembled the present collection of some two thousand narratives from the following seventeen states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. 2

The work of the Writers’ Unit in preparing the narratives for deposit in the Library of Congress consisted principally of arranging the manuscripts and photographs by states and alphabetically by informants within the states, listing the informants and illustrations, and collating the contents in seventeen volumes divided into thirty-three parts. The following material has been omitted: Most of the interviews with informants born too late to remember anything of significance regarding slavery or concerned chiefly with folklore; a few negligible fragments and unidentified manuscripts; a group of Tennessee interviews showing evidence of plagiarism; and the supplementary material gathered in connection with the narratives. In the course of the preparation of these volumes, the Writers’ Unit compiled data for an essay on the narratives and partially completed an index and a glossary. Enough additional material is being received from the state Writers’ Projects, as part of their surplus, to make a supplement, which, it is hoped, will contain several states not here represented, such as Louisiana.

All editing had previously been done in the states or the Washington office. Some of the penciled comments have been identified as those of John A. Lomax 3 and Alan Lomax, who also read the manuscripts. In a few cases, two drafts or versions of the same interview have been included for comparison of interesting variations or alterations.

Washington, D.C.

June 12, 1941

B.A. Botkin

Chief Editor, Writers’ Unit

Library of Congress Project

Citations:

- On August 31, 1939, the Federal Writers’ Project became the Writers’ Program, and the National Technical Project in Washington was terminated. On October 17, the first Library of Congress Project, under the sponsorship of the Library of Congress, was set up by the Work Projects Administration in the District of Columbia, to continue some of the functions of the National Technical Project, chiefly those concerned with books of a regional or nationwide scope. On February 12, 1940, the project was reorganized along strictly conservation lines, and on August 16 it was succeeded by the present Library of Congress Project (Official Project No. 165-2-26-7, Work Project No. 540).[↩]

- The bulk of the Virginia narratives is still in the state office. Excerpts from these are included in The Negro in Virginia, compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Virginia, Sponsored by the Hampton Institute, Hastings House, Publishers, New York, 1940. Other slave narratives are published in Drums and Shadows, Survival Studies among the Georgia Coastal Negroes, Savannah Unit, Georgia Writers’ Project, Work Projects Administration, University of Georgia Press, 1940. A composite article, “Slaves,” based on excerpts from three interviews, was contributed by Elizabeth Lomax to the American Stuff issue of Direction, Vol. 1, No. 3, 1935.[↩]

- Mr. Lomax served from June 25, 1936, to October 23, 1937, with a ninety-day furlough beginning July 24, 1937. According to a memorandum written by Mr. Alsberg on March 23, 1937, Mr. Lomax was “in charge of the collection of folklore all over the United States for the Writers’ Project. In connection with this work he is making recordings of Negro songs and cowboy ballads. Though technically on the payroll of the Survey of Historical Records, his work is done for the Writers and the results will make several national volumes of folklore. The essays in the State Guides devoted to folklore are also under his supervision.” Since 1933 Mr. Lomax has been Honorary Curator of the Archive of American Folk Song, Library of Congress.[↩]