In spite of the labors of unnumbered chroniclers, it is not easy, if indeed it is possible, for us of this later generation to realize adequately the great patriotic uprising of the war times.

It began in the early days of 1861 with the assault on Fort Sumter, which, following a long and trying season of uncertainty, furnished the sudden shock that resolved the doubts of the wavering and changed the opinions of the incredulous. Immediately there swept over all the northern states a wave of intense national feeling, attended by scenes of patriotic and confident enthusiasm more noisy than far-sighted, and there was a resulting host of volunteers, who went forth for the service of ninety days with the largest hopes, and proportionate ignorance of the crisis which had come to the nation. Of these Connecticut furnished more than her allotted share, and Litchfield County a due proportion.

The climax of this excited period was supplied by the battle of Bull Run. There was surprise, and almost consternation, at the first news of this salutary event, but quickly following, a renewed rally of patriotic feeling, less excited but more determined, and with a clearer apprehension of the actual situation. The enlistment of volunteers for a longer term had been begun, and now went forward briskly for many months; regiment after regiment was enrolled, equipped, and sent southward, until, in the spring of 1862, the force of this movement began to spend itself. The national arms had met with some important successes during the winter, and a feeling of confidence had arisen in the invincibility of the Grand Army of the Potomac, which had been gathering and organizing under General McClellan for what the impatient country was disposed to think an interminable time. A War Department order in April, 1862, putting a stop to recruiting for the armies, added to the confidence, since an easy inference could be drawn from it, and the North settled down to await with high hopes the results of McClellan’s long expected advance.

Then came the campaign on the Peninsula. At first there was but meager news and a multitude of conflicting rumors about its fierce battles and famous retreat, but in the end the realization of the failure of this mighty effort. To the country it was a disappointment literally stunning in its proportions; but now at length there was revealed the magnitude of the task confronting the nation, and again there sprang up the determination, grim and intense, to strain every nerve for the restoration of the Union.

The President’s call for three hundred thousand men to serve “for three years or the war” was proclaimed to this state by Governor Buckingham on July 3rd (1862), and evidence was at once forthcoming that it was sternly heeded by the people. To fill Connecticut’s quota under this call, it was proposed that regiments should be raised by counties. A convention was promptly called, which met in Litchfield on July 22nd; delegates from every town in the county were in attendance, representatives of all shades of political opinion and individual bias, but the conclusions of the meeting were unanimously reached. It was resolved that Litchfield County should furnish an entire regiment of volunteers, and that Leverett W. Wessells, at that time Sheriff, should be recommended as its commander.

Immediate steps were taken to render this determination effective; the Governor promptly accepted the recommendation as to the colonelcy, recruiting officers were designated to secure enlistments, bounties voted by the different towns as proposed by the county meeting, and the movement thoroughly organized. Although there was a clear appreciation of the present need, the dozen or more Connecticut regiments already in the field had drawn a large number of men from Litchfield County, and effort was necessary to gain the required enrollment. There had been many opportunities already for all to volunteer who had any wish to do so, but the call now came to men who a few weeks before had hardly dreamed of the need of their serving; men not to be attracted by the excitement of a novel adventure, but who recognized soberly the duty that was presenting itself in this emergency, and men of a very different stamp from those drawn into the ranks in the later years of the war by enormous bounties. It is reasonable to think that pride in the success of the county’s effort was a factor in stimulating enlistments; announcement that a draft would be resorted to later was doubtless another. Just at this time, also, the return from a year’s captivity in the South of the Rev. Hiram Eddy of Winsted, who had been made prisoner at Bull Run, furnished a powerful advocate to the cause; night after night he spoke in different towns, urging the call to service fervently and with effect.

In the last week in August, the necessary number of recruits having been secured, the different companies were brought together in Litchfield and marched to the hill overlooking the town which had been selected as the location of Camp Dutton, named in honor of Lieutenant Henry M. Dutton, who had fallen in battle at Cedar Mountain shortly before. Lieutenant Dutton, the son of Governor Henry Dutton, was a graduate of Yale in the class of 1857, and was practicing law in Litchfield when he volunteered for service on the organization of the Fifth Connecticut Infantry.

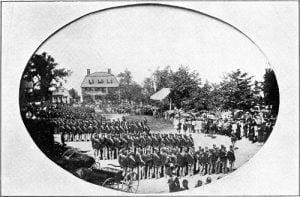

The interest and pride of the county in its own regiment was naturally of the strongest; the family that had no son or brother or cousin in its ranks seemed almost the exception, and Camp Dutton became at once the goal of a ceaseless stream of visitors from far and near, somewhat to the prejudice of those principles of military order and discipline which had now to be acquired. The preparation and drill which employed the scant two weeks spent here were supervised by Lieutenant-Colonel Kellogg, fresh from McClellan’s army in Virginia, and he was afterwards reported as delivering the opinion that if there were nine hundred men in the camp, there were certainly nine thousand women most of the time.

With all possible haste, preparations were made for an early departure, but there was opportunity for a formal mustering of the regiment in Litchfield, when a fine set of colors was presented by William Curtis Noyes, Esq., in behalf of his wife. A horse for the Colonel was given also, by the Hon. Robbins Battell, saddle and equipments by Judge Origen S. Seymour, and a sword by the deputies who had served under Sheriff Wessells.

“In order to raise it,” says the regimental history, “Litchfield County had given up the flower of her youth, the hope and pride of hundreds of families, and they had by no means enlisted to fight for a superior class of men at home. There was no superior class at home. In moral qualities, in social worth, in every civil relation, they were the best that Connecticut had to give. More than fifty of the rank and file of the regiment subsequently found their way to commissions, and at least a hundred more proved themselves not a whit less competent or worthy to wear sash and saber if it had been their fortune.”

The regimental officers were: Colonel, Leverett W. Wessells, Litchfield; lieutenant-colonel, Elisha S. Kellogg, Derby; major, Nathaniel Smith, Woodbury; adjutant, Charles J. Deming, Litchfield; quartermaster, Bradley D. Lee, Barkhamsted; chaplain, Jonathan A. Wainwright, Torrington; surgeon, Henry Plumb, New Milford.

Colonel Wessells, a native of Litchfield, and a brother of General Henry W. Wessells of the regular army, had been prominent in public affairs before the war, and served for twelve years as Sheriff. Ill health interfered with his service with the regiment from the first, and finally compelled his resignation in September, 1863. Later he was appointed Provost Marshal for the Fourth District of Connecticut, and for many years after the war was active in civil affairs, being the candidate for State Treasurer on the Republican ticket in 1868, Quartermaster-General on Governor Andrews’ staff, and member of the General Assembly. He died at Dover, Delaware, April 4, 1895.