I have the honour to inform you that I left St. John’s on the 28th May to visit the settlement of the Micmac Indians at Bay d’Espoir, on the south coast of this Island.

Bay d’Espoir is a long inlet of the sea, extending up country over a score of miles. The district is hilly, and is covered by a forest of rather small trees, spruce and birch, but further inland the hills are generally bare. There are comparatively few European residents in this bay.

The Micmac settlement is on a reservation situated on the eastern side of the Conne arm of the bay, with a frontage to the water of 230 chains, with an average depth of about 30 chains. It is on the slope of a wooded hill which is generally steep down to the sea, and at most places hard and rocky, covered by spruce forest. Most of the Micmac houses are on an area of about a quarter of a mile, where the ground is least steep and most suitable for building and gardening. In Appendix I. hereto is given a list of the 23 families, consisting of 131 persons, now living on or near the Reservation; and of the 7 persons that have left it for Glenwood in this Colony. Two years ago three families left the Reservation to settle at Lewisport, and have not returned.

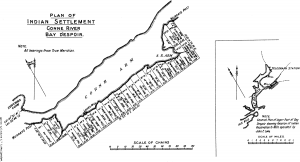

The Reservation, it appears, was laid off for the Micmacs about 1872, by Mr. Murray, Geological Surveyor of the Colony. It contained 24 blocks of about 30 acres each, with a water frontage of 10 chains. From the copy of the plan of the Reservation enclosed herewith it will be noticed that each parcel was to form the subject of a personal grant to the individual whose name is on the allotment. The right then conferred was in each case a “licence to occupy,” of which I enclose a copy in blank form. The licence, it will be observed, would, on the fulfilment of certain conditions, have been replaced by a grant in fee, after five years. In few cases, if in any, have the terms of the licence been complied with, and no grant in fee or other title has been issued to any of the occupants on this Reservation.

These Micmacs are hunters and trappers, and are ignorant alike of agriculture, of seamanship, and of fishing. There are not more than three or four acres of cultivated land in the whole settlement. The greatest cultivator would not grow in one year more than three or four barrels of potatoes and a few heads of cabbage. There are two miserable cows in the place, and some of the least poor Micmacs possess three or four extremely wretched sheep. They have practically no fowls, but I saw one fowl and a tame wild goose. Their houses are small and inferior, of sawn timber, but have windows of glass. A few hundred yards of road, constructed at the expense of the Government, traverses the end of the settlement where most of the people reside.

The community is Roman Catholic, and they have a small church, decently well built and kept, on the best site on the Reservation. It is built of sawn timber and would contain nearly one hundred people, which is too small for the festival of St. Anne, the patroness of the congregation. Over the entrance to the church there is printed in large characters, in the Micmac language, a total prohibition against spitting in church.The cemetery immediately adjoins the church, and there they bury their dead as members of a single family.

They have had a small school open since the 17th January last. It is a wooden room, about 12 feet by 15 feet, by no means new, with a small stove and two little windows.

The teacher is a woman of partly Micmac origin. She receives some very small allowance from the parish priest, and a few of the children, she says, pay some small fees. There are 34 children on the roll, and the winter attendance was from 25 to 30. They are divided into three classes, the highest of which could read slowly, in English, words of three or four letters. About half of them could write a little, a few of them surprisingly well on such brief tuition. The teacher says they are very amenable to discipline. Seldom has a school been started under greater difficulties than this Micmac institution. I was able sincerely to congratulate the teacher on what she has been able to accomplish under such unfavourable circumstances. It is manifest that the children are bright and clever, and that they would become useful and intelligent citizens if they had ordinary educational advantages. In this probably lies the best hope of a future prospect for this community. The settlement is visited now once a month by the parish priest; and in his absence, one of themselves, Stephen Jeddore, reads the service on Sunday. Last year they were visited by the Right Reverend Bishop McNeil.

They appear to be a comparatively healthy people. So far as known, no one is at present affected by tuberculosis in any form. I saw one woman of ninety years of age, Sarah Aseleka, perhaps the only Micmac of pure blood in the settlement. She was born at Bay St. George, and came to Bay d’Espoir some three score of years ago when the Micmacs first settled in this bay. The next oldest person is John Bernard, who is about eighty. Few of them were even fairly well clothed; the majority were in rags. A few wore home-made deer-skin boots, but most of them had purchased ready-made boots or shoes. They make deer-skin boots by scraping caribou skin, and tanning it in a decoction of spruce bark. Such boots are, they state, worn through in a few days. The women can spin wool, and knit stockings. Their food consists chiefly of flour, a few potatoes, some cabbage, and perhaps about half a score of caribou a year for each family, hung up on trees and thus frozen during the winter. They also smoke fish, principally freshwater fish, and obtain a few grouse and hares, but this small game has almost disappeared from the district. They have to go inland a score of miles to obtain caribou for food.The men are of good size, and strongly built, but clearly of mixed descent, many being nearly like Europeans. The children have all, without exception, very dark, soft eyes, straight black hair, and the nose much more prominent than in the Esquimaux of Labrador.

The principal Chief is Olibia, but I unfortunately did not meet him. He had gone out in March to his trapping ground near Mount Sylvester, but could not then reach his traps on account of the unusually great quantity of snow, and he had returned thither at the time of my visit.I was informed that he was selected as Chief by the Micmacs of the Reservation, and was appointed by the principal Micmac Chief at St. Anne’s, Nova Scotia, and by the priest. I was shown the insignia of office worn on ceremonial occasions by the Chief. It consists of a gold medallion with a chain attached, the whole in a case covered by red velvet. The medallion is inscribed “Presented to the Chief of the Micmacs Indians of Newfoundland,” but with neither name nor date. The community paid for this badge of office forty-eight dollars.

The second chief is Geodol—called in English Noel Jeddore—who represented Olibia in his absence. Geodol is the owner of one of the two cows on the Reservation, and his brother possesses the second one. The Chieftainship is not hereditary, but is conferred, when a vacancy occurs, on the man the people prefer. They are easy to govern and seldom quarrel. They have no intoxicating liquor and seldom obtain any. They pay 60 to 70 cents a pound for their tobacco, 20 to 30 cents for gunpowder, and 10 cents for shot. They sell their fur locally where they make their small family purchases.

The head of each family has his own special trapping ground in the interior, over which others may travel, fish, or shoot, but not trap. For example Geodol, the second chief, traps about Gulp Lake; Olibia, the chief, about Mount Sylvester; Nicholas Jeddore about Burnt Hill; George Jeddore at Bare Hill and Middle Ridge; Stephen Jeddore at Scaffold Hill; Noel Matthews at Great Burnt Lake; &c.None go as far north as the railway, but Meiklejohn goes as far as John’s Pond. Europeans are encroaching on their trapping lands, but do not go far inland. This pushes the Micmacs further inland to get away from the Europeans. They claim no fishing rights at sea, and say frankly they are only trappers and guides.

They go inland in September, when their first care is to shoot a deer and smoke the flesh as food. They return home from the 20th to the 25th November to prepare their traps for fox, lynx, otter, and bear. In December they shoot, as winter food for the family, does and young stags, but not old stags. They say the arctic hare is now very rare on their trapping lands; and snipe, geese, and ducks are far fewer than they were a few years ago. They appear to be very careful not to waste venison, never killing any deer they do not actually require and use as food.

It is not possible to regard the present condition and the prospects of this settlement of Micmacs as being bright. Game, their principal food, is manifestly becoming more difficult to procure; their trapping lands are being encroached upon by Europeans; they are not seamen; they are not fishermen; and they do not understand agriculture. In the middle of their Reservation a saw-mill has been in operation some years, apparently on the allotment of Bernard John, but without his sanction or permission, and, it seems, in spite of the protests of the community. None of the Micmacs work at this mill. Formerly they cut logs for it, but the trees that grew near the water have, they say, all been used up and there are none left within their reach that they could bring to the water. The saw-mill is thus an eyesore to them, as it is on what they regard as their land, and in defiance of them.Although they have not complied with the conditions set forth on the form of licence, which would have entitled them to a grant in fee, yet their occupation has extended over so many years that there is no probability whatever that the Government of Newfoundland would withhold from them grants, as a matter of grace, if they only applied for them and could show how they could use the land. It would not be difficult to find a location for the community that would be more suitable for them so far as cultivation is concerned, and be equally good for hunting and trapping. With some aid, such as supplies of seed potatoes and a few animals, they could no doubt derive much greater resources than at present from agriculture, especially if to that were added a good school for the young.

The question of their trapping lands will have to be dealt with before long. Each man regards his rights to his trapping area as unimpeachable. They are recognised at present among themselves, but they have no official sanction for their trapping lands either as a community or as individuals, just as they have no official title to the Reservation.

I was accompanied on this visit by the Honourable Eli Dawe, Minister of Marine and Fisheries, who, as a member of the Government, will himself take an interest in the settlement, and call the attention of his colleagues to the condition of the Micmacs. I was also assisted by Mr. James Howley, who has been on friendly terms with these people for many years. I enclose photographs 1 of some of the Micmacs, taken by Mr. Howley during this visit.

The Micmacs are held by ethnologists to be a branch of the Algonquins, who inhabited Maine, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. It was from the last-named province that they extended to Newfoundland, apparently not much more than a century ago. The fact that they did not effect a lodgment on Newfoundland sooner may be at least partly accounted for by supposing that the Beothuks, the aboriginal natives of Newfoundland, were able to defend themselves and their country from the Micmacs so long as both sides were unprovided with firearms, and until the Beothuks were nearly destroyed by their French and English aggressors.A sufficiently accurate view of the arrival and early doings of the Micmacs in Newfoundland may be had from the brief extracts from official records enclosed herewith. Governor Duckworth reports in 1809 that the Micmacs were coming over, and that the Beothuks were keeping to the interior in dread of them. The Governor followed up this Report next year (1810) by a Proclamation to the Micmacs and other American Indians frequenting Newfoundland, warning them that any person that murdered a native Indian (Beothuk) would be punished with death. Unfortunately this Proclamation it would appear had no restraining effect, as Governor Keats reports to the Secretary of State in 1815 that the Micmacs had recently come over from Nova Scotia in greater numbers, and had reached the eastern coast of Newfoundland; and he expressed the fear that these newcomers would destroy the native Indians of the Island, whose arms were the bow and arrow.

The Micmacs, it appears, have always possessed firearms since they arrived in Newfoundland. On the other hand I have never heard of a single instance in which the native Beothuks ever obtained such a weapon. The fears of Governor Keats were therefore only too well founded. The unfortunate Beothuk was thus crushed out of existence by the white man and the invading Micmac. Between the white man and the Beothuk there was always hostility; and I have not heard of any family or person in Newfoundland in whose veins flows Beothuk blood. On the other hand it may be doubted whether there is a single pure-blooded Micmac on the Island to-day. As an ethnic unit the Micmac can therefore hardly be said to exist here.

At the same time the Micmac community, such as it is, will not, at least for several generations, be absorbed into the European population of Newfoundland. It is at present a separate entity, and as such clearly requires special attention and treatment at the hands of the Administration, for the Reservation families have claims on Newfoundland by right of a century of Micmac occupation, and by virtue of the European blood that probably each one of them has inherited.

Appendix I – List of Micmacs At Conne Settlement

https://accessgenealogy.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/238-Micmacs-At-Conne-Settlement-2016-10-06.csv is an Invalid Spreadsheet file.

Appendix II – Proclamation

Newfoundland.

To all to whom these Presents shall come, I, Anthony Musgrave, Esquire, Governor and Commander-in-Chief in and over the island of Newfoundland and its Dependencies, &c., &c.

Send Greeting:

Whereas

of desirous of permanently settling on the Land hereinafter mentioned: Know ye, that in pursuance of the power and authority vested in me by the Act of the Legislature of this Colony, passed in the 23rd year of the Reign of Her present Majesty, entitled “An Act to amend an Act passed in the Seventh year of Her Majesty’s Reign, entitled ‘An Act to make provision for the Disposal and Sale of ungranted and unoccupied Crown Lands, within the Island of Newfoundland and its Dependencies, and for other purposes’;” I, the said Governor, do hereby give to the said a License to Occupy all that Piece or Parcel of Land situate and being

To Have and to Hold the same, with all rights and all privileges thereto belonging, to the said Executors, Administrators and Assigns, for the term of Five Years from the date of these Presents: Provided always that if the said shall have settled on and occupied the said Land for the said term of Five Years, and have cultivated acres thereof, within the said term, and have conformed to the provisions of said Act, shall be entitled to a Grant in fee, under the Great Seal, for the said Land: but should he fail to comply with the conditions of this License and conform to the said Act, he shall forfeit all claim to the said Land and Grant aforesaid.

Given under my Hand and Seal at St. John’s in Our Island of Newfoundland, this

day of

Anno Domini One Thousand Eight

Hundred and

By His Excellency’s Command,

Colonial Secretary.

Appendix III – Letter from “Antelope”

“Antelope” at Spithead.

25th November, 1809.

I am sorry to inform Your Lordship that I am again disappointed in my hopes of coming at the Native Indians (Beothuks); they still keep in the interior of the Island (it is reported) from a dread of the Micmacs, who come over from Cape Breton. The articles that were purchased for them are deposited in the Naval Store House at St. John’s, where I have directed them to be kept for some future trial of meeting with them.

The Governor’s Address to the Micmacs, &c.

His Excellency, Sir John Thomas Duckworth, K.B., Vice-Admiral of the Red, Governor and Commander-in-Chief in and over the Island of Newfoundland, &c.

To the Micmacs, the Esquimaux, and other American Indians frequenting the said Island, Greeting:

Whereas it is the gracious pleasure of His Majesty the King, my master, that all kindness should be shewn to you in his Island of Newfoundland, and that all persons of all nations at friendship with him should be considered in this respect as his own subjects, and equally claiming his protection while they are within his Dominions: This is to greet you in His Majesty’s name and to entreat you to live in harmony with each other, and to consider all his subjects and all persons inhabiting in his Dominions as your brothers, always ready to do you service, to redress your grievances, and to relieve you in your distress. In the same light also are you to consider the native Indians of this Island; they too are, equally with ourselves, under the protection of our King, and therefore equally entitled to your friendship. You are entreated to behave to them on all occasions as you would do to ourselves. You know that we are your friends, and as they too are our friends, we beg you to be at peace with each other. And withal, you are hereby warned that the safety of these Indians is so precious to His Majesty, who is always the support of the feeble, that if one of ourselves were to do them wrong he would be punished as certainly and as severely as if the injury had been done to the greatest among his own people, and he who dared to murder any one of them would be severely punished with death; your own safety is in the same manner provided for; see therefore that you do no injury to them. If an Englishman were known to murder the poorest and the meanest of your Indians, his death would be the punishment of his crime. Do you not therefore deprive any one of our friends, the native Indians, of his life, or it will be answered with the life of him who has been guilty of murder.

Fort Townshend, St. John’s, Newfoundland,

1st August, 1810.

J.T. Duckworth.

Extract from Despatch from Governor Sir R.G. Keats to the Secretary of State, 10th November, 1815.

Some years ago the Micmac Indians formed a settlement in St. George’s Bay on the West Coast of Newfoundland, which is thriving and industrious. The success of this settlement has probably induced others to follow them, and latterly they have come over in more considerable numbers, penetrated into the country and shewn themselves the present season on the eastern coast of Newfoundland. It is to be feared the arrival of these new comers will prove fatal to the native Indians of the Island, whose arms are the bow, with whom their tribe as well as the Esquimaux are at war, and whose number it is believed has for some years past not exceeded a few hundred.

10th November, 1815.

Citations: