There has never been a scientific study to determine the post-colonial history of the Sephardic communities in the Southern Piedmont and Appalachians. Anything that can be said must be in the realm of speculation, based on the known cultural history of the Southeast during the Colonial and Antebellum Eras. The only significant religious-based persecution in the Lower Southeast was between the Sephardic Jews and the Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe. A Protestant minister in Savannah wrote, “Some Jews in Savannah complain that the Spanish and Portuguese Jews should persecute the German Jews in a way no Christian would persecute another Christian.”

One of the biggest obstacles to tracing early Sephardic Jewish colonists in the Appalachians is the general acceptance that Jewish citizens received in the Southeast. Unlike the situation in Spanish and French colonies, they were not forbidden entry. Unlike in the North, Jewish settlers were not pressured into the ghettos of large cities. However, for many decades the only Southern synagogues were in old colonial cities such as Savannah, Charleston, Wilmington and Richmond. 1 Most of the Jewish immigrants were dispersed as individual families across the landscape of the Southeast’s towns and plantations. The earliest Jewish settlers were Sephardim. German and Eastern European Jews followed.

There was apparently little social stigma in the Old South toward marriage between affluent Jews and Christians. Several prominent Christian and Jewish leaders of that era embarked on happy marriages with spouses of the other religion. 2 Some of their children became Christian. Some became Jewish. All carried forward a general tolerance for both faiths. Many, if not most, early Jewish settlers, who were isolated in small Southern towns, eventually became Methodists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists or Unitarians. By the late 20th century their descendants probably were not aware of the Jewish heritage.

The Sephardic Jews were often professionals and scholars in Spain, Portugal and Netherlands. Their skills were needed and welcomed in the agricultural economy of the South. Sephardic Jewish doctors, dentists, lawyers, printers, builders and accountants established businesses in hundreds of towns throughout the Southeast, especially in Georgia, Louisiana and eastern Texas. A Jewish doctor, Albert Moses Levy, was surgeon for the New Orleans Grays when they helped capture San Antonio de Bexar and the Alamo. He later served in the Republic of Texas Navy.

The Jewish immigrants also became politicians. Mordecai Sheftall of Savannah was the highest ranking officials in the Revolutionary Period American government. Francis Salvador, a Sephardi in South Carolina, was the first Jew to be elected to a colonial legislature. 3 A few years later, he would become a hero of the Revolution. The British unleashed a massive attack by the Cherokees on July 1 against the frontier settlements of South Carolina, 1776 in hopes of discouraging approval of the Declaration of Independence. Patriots, Neutrals and Loyalists were massacred alike.

On that day, Francis Salvador galloped his horse for over 28 miles to warn the frontier militia that Cherokee raiders were coming. A month later, two captured Tories led the militia army into trap set by Tories and Cherokees from the village of Seneca. Salvador was wounded and fell into the brush. He was scalped by the Cherokees, left for dead, but then rescued by the victorious South Carolina militia. He died the next day.

One of Georgia’s first governors, David Emmanuel, was a Sephardic Jew. Later in life became a Presbyterian, but of course, genetically, he was still Jewish. David Yulee was a Sephardic Jew from Florida who became the first Jewish United States Senator. The second Jewish United States Senator was Benjamin Judah, representing the state of Louisiana. 4

Judah was a Sephardic Jew, who was born in St. Croix in the Virgin Islands. He grew up in North Carolina and South Carolina. After graduation from college married a Creole Belle and moved to Louisiana. Judah later became the first Jew is serve in the President’s Cabinet as Secretary of War and later, Attorney General. That’s Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s Cabinet, of course. There would not be a Jewish member of the United States Cabinet until 1906.

North and South Carolina Jewish Colonists

From its beginning in 1670, the Colony of Carolina permitted Jews to immigrate there. 5 The first specific mention of a Jewish colonist, however, was in 1695. Presumably the Sephardic Jewish families living in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain prior to English settlement, either intermarried so much with Native Americans that they were viewed as such, or assimilated into the Anglo-Celtic culture. There are isolated rural pockets of Carolinians that still claim “Portuguese” ancestry.

No formal Jewish congregation existed in the Carolinas until 1749.Congregation Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim was founded in that year, but initially met for prayer services in homes. The majority of its founders were Sephardic Jews. By 1824, the synagogue’s members had become so assimilated that they requested that the Orthodox Sephardic liturgy be replaced by prayers and sermons in English. This synagogue is considered to be the founder of Reformed Judaism.

North Carolina’s official histories completely omit the existence of early Jewish settlers in their state. Officially, the first Jew to arrive was Aaron Moses in 1740. 6 In contrast, James Adair stated in his book, “The History of the American Indians” that several hundred Cherokees, living in the North Carolina Mountains, spoke an ancient Jewish language that was nearly unintelligible to Jews from England and Holland. 7 From this observation, Adair extrapolated a belief that all Native Americans were the descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.

Surviving British colonial archives strongly suggest that Spanish-speaking settlers in the mountains of western North Carolina were viewed by colonial authorities in Charleston as “enemies” in the late 1600s and early 1700s. South Carolina authorities controlled trade with the Cherokees of the western North Carolina Mountains and claimed northern Georgia until 1785. In two surviving accounts, the Cherokees bragged to South Carolina officials that they had killed or driven out Spanish-speaking villagers, that appear to be have been Orthodox Jews.

It is likely that all male Spanish-speaking Jewish colonists in the North Carolina Mountains were either killed or driven out during the Queen Anne’s War with Spain (1702–1713) or the early phase of the Yamasee War (1715.) Several Jewish men were known to have become Indian traders. Those based in South Carolina, who were in Cherokee territory at the time, were definitely killed. Female and juvenile Jewish captives may have been incorporated into Cherokee communities. It was typical of the Rickohockens, Westos and Cherokees to kill all adult and teenage males when capturing a village. 8

Georgia Jewish Colonists

The attitude of General James Edward Oglethorpe, leader of the Georgia Colony was very clear. Sephardic Jews were viewed as strong supporters of Great Britain, arch-enemies of Spain and valuable cultural assets to the colony. Portuguese/Spanish speaking Jews arrived in Savannah in 1733, the same year that the Colony of Georgia was founded. Congregation Kahal Kadosh Mickva Israel was founded in 1735. It is the third oldest synagogue in North America. Savannah’s first medical doctor was a Portuguese Jew named Samuel Nunes. His former job was Court Physician to the King of Portugal.

During the war with Spain in 1742-1745, most Sephardic Jews left Savannah when Spanish troops invaded Georgia. They feared that they would be burned at the stake. A few Sephardim returned to Savannah after a combined army of Georgia colonial militia and Creek Indians defeated the Spanish. However, thereafter, the congregation contained a higher percentage of Ashkenazi Jews.

There is very little information in the Georgia Colonial archives about what was going on in northern Georgia during the period from 1733 to 1776. To date no mention has been found of Jewish residents in the region during that period. The Creek-Cherokee War flared intermittently between 1715 and 1754, often making the Georgia Mountains a battleground. Creek towns were fortified, so Cherokee attacks were always on bands of Creek hunters or travelers. In contrast, the Creeks invariably attacked the unfortified Cherokee villages. There is no record of Creeks killing or driving out Jewish settlers.

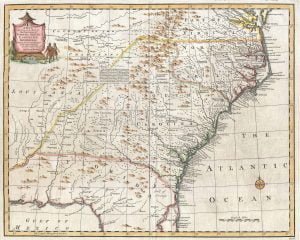

Various branches of the Creeks such as the Kusa (Coosa,) Koweta, Apalache and Okonee occupied most of the Georgia Mountains, but Georgia maps also show Chickasaw, Yuchi and Savano (Shawnee) communities. 9 All but a few geographical place names in the region are Muskogean in origin, but include the names of tribes such as the Sawate (Saute), Eno (Mount Enotah), Tenasa (Tesnatee Mountain) and Soque (Soque River) that were Muskogeans indigenous to South Carolina. Any one of these many tribes could have contained people of Jewish ancestry. It is quite probable, given the Creek tradition of absorbing minorities, but not known for certain.

James Adair’s Ten Lost Tribes of Israel

The appearance of definite Jewish DNA in some Cherokees, Melungeons and Creeks has caused a renewed interest in James Adair. As stated earlier, his book, History of the American Indians, dwells on his theory that the Southeastern Indians were the descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.

There is also some evidence that there were Jewish families living in the Chickasaw territory of extreme northwestern Georgia. This is because of statements made by Indian trader James Adair. 10 His Chickasaw wife was of partial Jewish heritage that gave her some Caucasian features. When the Cherokees attacked the South Carolina frontier in 1776, Adair moved his wife and mixed heritage family to Oothlooga Creek near present day Adairsville, GA (northwest Georgia). The location was supposedly near her relatives. Does that mean that there were Sephardic or mixed-blood Sephardic-Native American settlers in northwest Georgia? The books are silent. However, Adairsville is on the edge of the Georgia Gold Belt. Spanish weapons, armor, jewelry and pottery have been found in the region where Adairsville is located.

The South Carolina and Wikipedia version of Adair’s life has him living most of the time at a farmstead in Laurens County, South Carolina. An in-depth investigation of his life by a professional historian and also the Alabama Encyclopedia, state that he spent very little time in South Carolina after 1745 and his whereabouts, after 1775, cannot be verified. His real last name may have not been Adair as his claimed birth in Antrim County, Ireland in 1709 has not been confirmed. It is known that before the Revolution, he spent much time at New Windsor, a Chickasaw village on the upper Savannah River in northeast Georgia. In the French and Indian War he was a lieutenant in command of a company of northwest Georgia/northeast Alabama Chickasaws, who fought the Cherokees. From his own statements, it is known that he also spent some periods of time at the Holston River settlements, but spent much of the time between 1763 and 1775 working on his book about the Southeastern Indians.

Adair’s mixed heritage sons stayed in Georgia, where they operated grist mills, forges and lumber mills. When the Cherokees moved into northwest Georgia in the 1780s, the Adair brothers remained. They became leaders of the Cherokee Nation. Adair is still a prominent name among both the Cherokee and Creek Nations in Oklahoma.

What particularly intrigues researchers is Adair’s extensive knowledge of the Jewish languages and writing system. 11 He knew both archaic Hebrew and Late Medieval Hebrew. He was obviously a well educated man. This should not have been the case for a man who spent his adult life in a frontier log cabin. There is also evidence that on arrival in America, he immediately went to the Holston River Valley, which at that time had no white inhabitants, according to official American history. Was James Adair actually a Sephardic Jew, who wrote his book to attract other European Jews to Tennessee? The jury is still out deliberating on that question.

Tennessee Jewish Colonists

The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture opens an article on“Jewish Settlement in Tennessee” by Peter J. Haas, with the following statement: “The earliest Jewish settlers arrived in Tennessee in the 1830s and 1840s, having fled the political turmoil of German-speaking areas with other Central Europeans.” 12 There is no mention of the early Sephardic settlements in the state. Another article in this online encyclopedia on the Melungeons by Ann Toplovich of Tennessee Historical Society, mentions the possible Portuguese and Moorish ancestry of the Melungeons, but does not mention that virtually all the “Portuguese” colonists in the Southeast were actually Sephardic Jews. 13

Apparently, unlike the situation in Georgia, where Sephardic Jews played a significant role in the early history of the state, the Tennessee Sephardim did not . . . or at least they disappeared from the cultural “radar screen.” Did these Jewish Tennesseans change their names, change their religion or move away?

It is absolutely certain that Sephardic Jews were originally in northeastern Tennessee. Eyewitness accounts from the late 1700s, such as those from Colonel John Tipton and Colonel John Sevier are reliable proof that during that era, there were still large numbers of Spanish or Portuguese speaking Jews in northeastern Tennessee.

Eyewitness reports from the late 1600s also place Orthodox or Catholic Christians in northeastern Tennessee, but they were apparently gone by the late 1700s. They possibly left when the Cherokees organized into a tribe or when France lost the French and Indian War. As will be discussed later, they may well have been chased out by English subjects of Sephardic Jewish ancestry. The Sephardim hated the Spanish and Portuguese Catholics. There would not have been as much hostility toward Orthodox Christians. However, the Sephardim and Protestants had been political allies since the mid-1500s.

The most likely explanation of the fate of the Sephardic settlers of Tennessee is that they moved down into Alabama or to newly available lands along the Mississippi River after the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory. Perhaps they didn’t have clear titles to their Tennessee farms and were evicted by real estate speculators with political connections. France had attempted to block Protestants and Jews from settling in Canada and Louisiana. Suddenly, Jews could settle anywhere in the vast Louisiana Territory. Jews involved in commerce were particularly attracted to St. Louis and New Orleans.

Sephardic Jews living in remote valleys may have continued to live there. A member of the People of One Fire research alliance confided with the author that she always knew that there was something “different” about her family. 14 She grew up in northeastern Tennessee. Her family elders were very vague as to when they arrived in Tennessee, but it was obviously very early. None of her extended family attended church, but prayed daily to God. In fact, many of her relatives were quite spiritual and devout. When she asked her mother why they didn’t go to church in town like her friends at school, she was told “our family does not observe Sunday as a holy day like the folks in town do.” When asked about their dark hair and eyes, the woman’s parents told her that they were part Indian, but didn’t say which “Indians.” The family had special prayer services around Easter, but not on Easter Sunday. In retrospect, the woman realized that her family was probably descended from Sephardic Jews.

The Cryptic History of Tennessee

In contrast to the official histories of Tennessee, written by university history professors, the articles written by genealogists and local historians abound with references to Tennessee’s Jewish settlers living in eastern Tennessee before the American Revolution. Several online web pages describe the Holston River Valley as “the original homeland of the Jews in America.” Research by Elizabeth Hirschman confirmed this tradition. 15

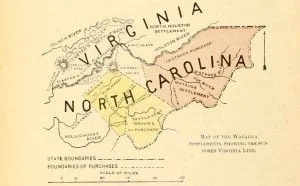

The Watauga Settlement was founded in 1772 on lands along the Holston River in what is now northeastern Tennessee. The official story is that the lands were bought from Cherokee chiefs. However, these lands were by royal proclamation in 1763, off limits from white settlement, even thought English subjects had been living there since before 1650.

Official American histories state that the Watauga Settlement was more and less a spontaneous entity created by illiterate, land hungry Englishmen. There is no explanation in the official history why neither South Carolina nor North Carolina dispatched military units to evict the Watauga settlers.

Dr. Elizabeth Hirschman of Rutgers University has thoroughly researched the family histories of several of the pioneers who founded Tennessee. 16 Many of them such as Daniel Boone and John Sevier had Jewish roots, or even had changed their Jewish names to English forms. She also discovered that land acquisition for the Watauga Settlement and the State of Franklin in northeastern Tennessee was funded by wealthy Sephardic Jews living in London. The Watauga Settlement was not a spontaneous event.

“Germans” from the Shenandoah Valley flooded into northeastern Tennessee in the 1780s, led by John Tipton and John Sevier. What Hirschman suspected was that among those “Germans” from Shenandoah County, VA were many Dutch Jews. She was correct in her suspicion. This fact was discussed in Chapter One. That John Sevier was probably of Jewish heritage makes her theory even more plausible.

Citations:

- Raphael, Marc Lee, The Synagogue in America, New York: New York University Press, 2011.[↩]

- Evans, Eli, The Provincials: A Personal History of Jews in the South, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.[↩]

- Pencak, William, Jews and Gentiles in Early America 1654-1800, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005.[↩]

- Rosen, Robert N., The Jewish Confederates, University of South Carolina Press, 2000.[↩]

- Joshua Levs, The Jews of South Carolina, Exhibit Highlights 300 Years of Tradition, Assimilation and Conflict, South Carolina Public Radio Website, 2002.[↩]

- Rogoff, Leonard, Down Home, Jewish Life in North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.[↩]

- Braund, Kathryn E. Holland. James Adair: His Life and History, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005, pp. 1-53.[↩]

- Thornton, Richard. The Westo Indians and Native American Slavery. Examiner.com. 26 October 2012.[↩]

- Bowen, Emanuel, A New Map of Georgia, with Part of Carolina, Florida and Louisiana. Drawn from Original Draughts assisted by the most approved Maps and Charts, 1748.[↩]

- Adair, James, History of the American Indians, 1775, pp. 1-57.[↩]

- Braund, Kathryn E. Holland. James Adair: His Life and History, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005, pp. 1-53.[↩]

- Haas, Peter J., Jewish Settlement in Tennessee, Tennessee Encyclopedia.[↩]

- Toplovich, Ann, The Melungeons, Tennessee Encyclopedia.[↩]

- This lady describing her crypto-Jewish heritage requested to remain anonymous.[↩]

- Hirschman, Elizabeth, The Melungeons: The Last Lost Tribe in America, Macon: Mercer University Press, 2004.[↩]

- Hirschman, Elizabeth, The Melungeons: The Last Lost Tribe in America, Macon: Mercer University Press, 2004.[↩]