Winema

Winema (‘woman chief’). A Modoc woman, better known as Toby Riddle, born in the spring of 1842. She received her name, Kaitchkona Winenta (Kitchkani laki shnawedsh, ‘female sub-chief’), because, when a child, she guided a canoe safely through the rapids of Link River. She justified her title when, but 15 years of age, she rallied the Modoc warriors as they took to flight when surprised by a band of Achomawi. After she grew up she became the wife of Frank Riddle, a miner from Kentucky. When the Modoc left Klamath reservation in 1872 to return to Lost River he served as interpreter to the various commissions that treated with them. After they had fled to the lava-beds and had defeated a detachment of soldiers, the Government decided to send a commission of men known to be in sympathy with them to arrange a peace. Winema warned Commissioner Meacham of the murderous temper of some of Captain Jack’s followers (see Kintpuash). Meacham was convinced and told his fellow commissioners, Gen. Edward R. S. Canby and Rev. E. Thomas, that they were going to their death, but could not swerve them from their purpose. Shonchin, the shaman, threatened to kill her unless she confessed who had betrayed the plot, but she declared that she was not afraid to die, and Captain Jack forbade him to shoot a woman. When Gen. Canby refused to withdraw the troops from the lava-beds, the Modoc chief gave the signal, and Canby and Thomas fell instantly. Shonchin then turned his rifle upon Meacham. Winema, who was present as interpreter, pleaded for the life of the man who, when Indian superintendent, had presented to white men living with Indian women the alternative of legal marriage or criminal prosecution. She seized the chief’s wrists and thrust herself between the assassins and the victim, and when he dropped from several bullet wounds and a Modoc seized his hair to take the scalp Winema cried out that the soldiers were coming, where upon they all fled. When the soldiers came at last, she advanced alone to meet them. Meacham, crippled and invalided, afterward took Winema with her son and Riddle, one of the two whites who escaped from the massacre, to the east to continue his intercession in behalf of the Indians, especially the Modoc, who had so perfidiously requited his previous benevolence.

Further Reading

Scarface Charley

A celebrated warrior, best known through his connection with Capt Jack, or Kintpuash, during the Modoc war of 1873. By the natives he was known as Chǐkclǐkam-Lupalkuelátko, meaning ‘wagon scar-faced,’ whence the name by which he was known to the whites by reason of a disfigurement caused by his having been run over by a mail stage when a child. Capt Jack spoke of him as a relative, but it is said also that he was a Rogue River Indian of the Tipsoe Tyee (Bearded Chief’s) band and joined Capt Jack some years prior to the war of 1873, when 22 years of age. Scarface was among those who taunted Jack when, after the first attack and repulse of the white soldiers, he was disposed to enter into a treaty of peace. When the Modoc became angered during Judge Steele‘s last visit to them in the lava-beds, Scarface and Capt Jack saved the life of Steele by guarding him during the night; and when Odeneal and Dyar visited the Modoc, Jan. 27, 1873, on behalf of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Scarface would have killed them on the spot had he not been restrained by Jack. He was also the first to fire on the troops when Capt Jackson attempted the arrest of Jack’s band on Jan. 28.

Rev Dr. Thomas, who was killed in the peace commission massacre, on the day before his death called Scarface Charley the “Leonidas of the lava-beds.” He was never known to be guilty of any act not authorized by the laws of legitimate warfare, and entered his earnest protest against the killing of Gen. Canby and Dr Thomas. He led the Modoc against Maj. Thomas and Col. Wright when the troops were so disastrously repulsed with a loss of about two-thirds in killed and wounded. Wearied of the slaughter, he is said to have shouted to the survivors, “You who are not dead had better go home; we don’t want to kill you all in a day!” Later he said, ” My heart was sick at seeing so many men killed.”

Scarface Charley was one of the witnesses called to testify in behalf of the Modoc prisoners during their trial in July following. He was sent with other prisoners successively to Ft D. A. Russell, Wyoming, Ft McPherson, Nebraska, and the Quapaw agency, Indian Territory, where he died about Dec. 3, 1896.

Further Reading:

Schonchin

The recognized head-chief of the Modoc at the time of the Modoc war of 1872-73. In 1846 the Modoc numbered 600 warriors, governed by Schonchin, whose authority seems even then to have been disputed on the ground that he was not an hereditary chief. He took an active part in the early hostilities between the Modoc and the whites, and admitted that he did all in his power to exterminate his enemies. Hostilities were continued at intervals until 1864, when a treaty was made with the Modoc by the provisions of which they agreed to go on a reservation with the Klamath Indians. At this council the Modoc were represented by Schonchin and his younger brother, known as Schonchin John. To the credit of the old chief it is said that after signing the treaty no act of his deserved censure. He went with his people on the land allotted to them, and at the time of the outbreak under Kintpuash, or Captain Jack, remained quietly on the reservation in charge of his peaceful tribesmen. His brother John, following Captain Jack, withdrew from the reservation and took up his abode on Lost River, the former home of the tribe. The old chief made every effort to induce Jack to return, but the latter steadfastly refused, on the ground that he could not live in peace with the Klamath. In order to remove every obstacle to the return of the fugitives, the reservation was divided into distinct agencies, a district being set apart exclusively for the Modoc. To this new home old Schonchin was removed with his people, and a portion of Captain Jack’s band took up their abode with him. The rest, including Schonchin John, fled to the lava beds, and from this stronghold waged a destructive war. It is believed that Schonchin John, more than any other member of the tribe, was influential in keeping up the strife. He repeatedly advised continuing the fight when Jack would have made peace, and he is considered responsible for many of the inhuman acts committed. In 1873 a peace commission was appointed to deal with the Indians, and a meeting with them was arranged for April 11. To this meeting the Indians agreed to send a number of men equal to that of the commission, and that all should go unarmed.

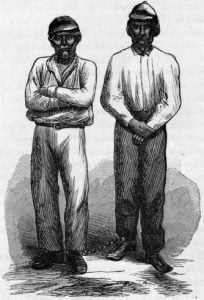

The commission were divided as to the advisability of keeping the appointment. Commissioners Dyar and Meacham suspected treachery and were of the opinion that it was not safe, while General Canby and Dr Thomas, a Methodist minister, insisted that it was plainly their duty to go. The four commissioners, accompanied by an interpreter and his Indian wife, proceeded to the place of appointment, and, being met by eight Indians, fully armed, it was evident that they had fallen into a trap. The council was opened with brief speeches by Thomas and Canby offering the terms of peace, only to be interrupted by Schonchin John, who angrily commanded, “Take away your soldiers and give us Hot Creek for a home!” Before the commissioners could reply, at a signal from Jack the Indians fell upon the white men. Canby and Thomas were shot to death, Dyar fled and escaped, and Meacham was shot five times by Schonchin John, but finally recovered. As a result of this massacre military operations were resumed with great activity, and after a few severe engagements Jack was dislodged from the lava beds and with his party surrendered on June 1. Gen. Davis decided to hang the leaders forthwith, Schonchin John among the number. While the scaffolds were being prepared word was received from Washington that the condemned men must be tried by a military commission. The prisoners were found guilty of murder and assault to kill, in violation of the rules of war, and sentenced to be hanged, but sentences of two of them were commuted to imprisonment for life. Schonchin John was one of those who were hanged. The execution took place at Ft Klamath, Oct. 3, 1873. In a speech made by Schonchin immediately before his death he declared that his execution would be a great injustice, that his “heart was good,” and that he had not committed murder. He asked that his children should be sent to his brother Schonchin, who was still at Yainax on the reservation, and who would “bring them up to be good.” Bancroft says that Schonchin John was striking in appearance, with a sensitive face, showing in its changing expression that he noted and felt all that was passing about him. Had he not been deeply wrinkled, though not more than 45 years of age, his countenance would have been rather pleasing.