During the night thirty-three bodies were brought to one house. As yet the relief force is not perfectly organized and bodies are lying around on boards and doors. Within twenty feet of where this was written the dead body of a colored woman lies.

Provision has been made by the Relief Committee for the sufferers to send despatches to all parts of the country. The railroad company has a track through to the bridge. The first train arrived about half-past nine o’clock this morning. A man in a frail craft got caught in the rapids at the railroad bridge, and it looked as if he would increase the already terrible list of dead, but fortunately he caught on a rock, where he now is and is liable to remain all day.

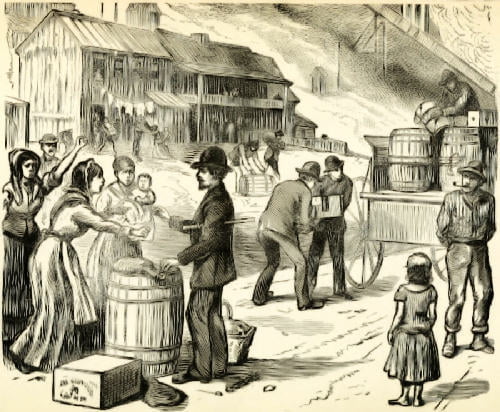

The question on every person’s lips is–Will the Cambria Iron Company rebuild? The wire mill is completely wrecked, but the walls of the rolling mill are still standing. If they do not resume it is a question whether the town will be rebuilt. The Hungarians were beginning to pillage the houses, and the arrival of police was most timely. Word had just been received that all the men employed by Peabody, the Pittsburgh contractor, have been saved.

The worst part of this disaster has not been told. Indeed, the most graphic description that can be written will not tell half the tale. No pen can describe nor tongue tell the vastness of this devastation.

I walked over the greater part of the wrecked town this morning, and one could not have pictured such a wreck, nor could one have imagined that an entire town of this size could be so completely swept away.

A.J. Haws, one of the prominent men of the town, was standing on the hillside this morning, taking a view of the wreck. He said:

“I never saw anything like this, nor do I believe any one else ever did. No idea can be had of the tremendous loss of property here. It amounts up into the millions. I am going to leave the place. I never will build here.”

I heard the superintendents and managers of the Cambria Iron Works saying they doubted if the works will be rebuilt. This would mean the death blow to the place. Mr. Stackhouse, first vice-president of the iron works, is expected here to-day. Nothing can be done until a meeting of the company is held.

Preparations for Burial

Adjutant General Hastings, who is in charge of the relief corps at the railroad station, has a force of carpenters at work making rough boxes in which to bury the dead. They will be buried on the hill, just above the town, on ground belonging to the Cambria Iron Company. The graves will be numbered. No one will be buried that has not been identified without a careful description being taken. General Hastings drove fifty-eight miles across the country in order to get here, and as soon as he came took charge. He has the whole town organized, and in connection with L.S. Smith has commenced the building of bridges and clearing away the wrecks to get out the dead bodies.

General Hastings has a large force of men clearing private tracks of the Cambria Iron Company in order that the small engines can be put to work bringing up the dead that have been dragged out of the river at points below.

The bodies are being brought up and laid out in freight cars. Mr. Kittle, of Ebensburg, has been deputized to take charge of the valuables taken from the bodies and keep a registry of them, and also to note any marks of identification that may be found. A number of the bodies have been stripped of rings or bracelets and other valuables.

Over six hundred corpses have now been taken out on the south side of Stony Creek, the greater portion of which have been identified.

Send Us Coffins

Preparations for their burial are being carried on as rapidly as possible, and “coffins, coffins,” is the cry. No word has been received anywhere of any being shipped. Even rough boxes will be gladly received. Those that are being made, and in which many of the bodies are being buried, are of rough unplaned boards. One hundred dead bodies are laid out at the soap factory, while two hundred or more people are gathered there that are in great distress. Boats are wanted. People have the greatest difficulty in getting to the town.

Struggling for Order

Another account from Johnstown on the second day after the disaster says:

The situation here has not changed, and yesterday’s estimates of the loss of life do not seem to be exaggerated. Six hundred bodies are now lying in Johnstown, and a large number have already been buried. Four immense relief trains arrived last night, and the survivors are being well cared for.

Adjutant General Hastings, assisted by Mayor Sanger, has taken command at Johnstown and vicinity. Nothing is legal unless it bears the signature of the former. The town itself is guarded by Company H, Sixth regiment, Lieutenant Leggett in command. New members were sworn in by him, and they are making excellent soldiers.

Special police are numerous, and the regulations are so strict that even the smoking of a cigar is prohibited. General Hastings expresses the opinion that more troops are necessary.

Mr. Alex. Hart is in charge of the special police. He has lost his wife and family. Notwithstanding his great misfortune he is doing the work of a Hercules in his own way.

Firemen and Soldiers Arriving

Chief Evans, of the Pittsburgh Fire Department, arrived this evening with engines and several hose carts, with a full complement of men. A large number of Pittsburgh physicians came on the same train.

A squad of Battery B, under command of Lieutenant Brown, the forerunners of the whole battery, arrived at the improvised telegraph office at half-past six o’clock. Lieutenant Brown went at once to Adjutant General Hastings and reported for duty.

A portion of the police force of Pittsburgh and Alleghany are on duty, and better order is maintained than prevailed yesterday. Communication has been restored between Cambria City and Johnstown by a foot bridge.

The work of repairing the tracks between Sang Hollow and Johnstown is going on rapidly, and trains will probably be running by to-morrow morning. Not less than fifteen thousand strangers are here.

The unruly element has been put down and order is now perfect. The Citizen’s Committee are in charge and have matters well organized.

A proclamation has just been issued that all men who are able to work must report for work or leave the place. “We have too much to do to support idlers,” says the Citizen’s Committee, “And will not abuse the generous help that is being sent by doing so.” From to-morrow all will be at work.

Money now is greatly needed to meet the heavy pay rolls that will be incurred for the next two weeks. W. C. Lewis, Chairman of the Finance Committee, is ready to receive the same.

Fall of the Wall of Water

Mr. Crouse, proprietor of the South Fork Fishing Club Hotel, came to Johnstown this afternoon. He says:–

“When the dam of Conemaugh Lake broke the water seemed to leap, scarcely touching the ground. It bounded down the valley, crashing and roaring, carrying everything before it. For a mile its front seemed like a solid wall twenty feet high.”

Freight Agent Dechert, when the great wall that held the body of water began to crumble at the top sent a message begging the people of Johnstown for God’s sake to take to the hills. He reports no serious accidents at South Fork.

Richard Davis ran to Prospect Hill when the water raised. As to Mr. Dechert’s message, he says just such have been sent down at each flood since the lake was made. The warning so often proved useless that little attention was paid to it this time. “I cannot describe the mad rush,” he said. “At first it looked like dust. That must have been the spray. I could see houses going down before it like a child’s play blocks set on edge in a row. As it came nearer I could see houses totter for a moment, then rise and the next moment be crushed like egg shells against each other.”

To Rise Phoenix-like

James McMillin, vice-president of the Cambria Iron Works, was met this afternoon. In a conversation he said:

“I do not know what our loss is. I cannot even estimate, as I have not the faintest idea what it may be. The upper mill is totally wrecked–damaged beyond all possibility of repairs. The lower mill is damaged to such an extent that all machinery and buildings are useless.

“The mills will be rebuilt immediately. I have sent out orders that all men that can must report at the mill to-morrow to commence cleaning up. I do not think the building was insured against a flood. The great thing we want is to get the mill in operation again.”

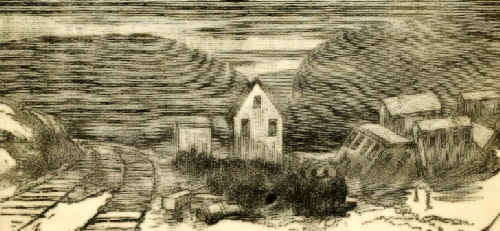

The Gautier Wire Works was completely destroyed. The buildings will be immediately rebuilt and put in operation as soon as possible. The loss at this point is complete. The land on which it stood is to-day as barren and desolate as if it were in the midst of the Sahara Desert.

The Cambria Iron Company loses its great supply stores. The damage to the stock alone will amount to $50,000.

The building was valued at $150,000, and is a total loss. The company offices which adjoins the store was a handsome structure. It was protected by the first building, but nevertheless is almost totally destroyed.

The Dartmouth Club, at which employees of the works boarded, was carried away in the flood. It contained many occupants at the time. None were saved.

Estimates of the losses of the Cambria Iron Company given are from $2,000,000 to $2,500,000. But little of this can be recovered.

History of the Cambria Iron Company Works

The Cambria Iron Works at Johnstown were built in 1853. It was the second largest plant of its kind in the country, and was completely swept away. Its capacity of finished steel per annum was 180,000 net tons of steel rails and 20,000 net tons of steel in other shapes. The mill turned out steel rails, spike bars, angles, flats, rounds, axles, billets and wire rods. There were nine Siemens and forty-two reverbatory heating furnaces, one seven ton and two 6,000 pound hammers and three trains of rolls.

The Bessemer Steel Works made their first blow July 10, 1871, and they contained nine gross ton converters, with an annual capacity of 200,000 net tons of ingots. In 1878 two fifteen gross tons Siemens open-hearth steel furnaces were built, with an annual capacity of 20,000 net tons of ingots.

The Cambria Iron Company also owns the Gautier Steel Works at Johnstown, which were erected in 1878.

The rolling mill produced annually 30,000 net tons of merchant bar steel of every size and for every purpose. The wire mill had a capacity alone of 30,000 tons of fence wire.

There are numerous bituminous coal mines near Johnstown, operated by the Cambria Iron Company, the Euclid Coal Company and private persons. There were three woolen mills, employing over three hundred hands and producing an annual product valued at $300,000.

Awful Work of the Flames

Fifty acres of town swept clean. One thousand two hundred buildings destroyed. Eight thousand to ten thousand lives lost.

That is the record of the Johnstown calamity as it looked to me just before dark last night. Acres of the town were turned into cemeteries, and miles of the river bank were involuntary storage rooms for household goods.

From the half ruined parapet at the end of the stone railroad bridge, in Johnstown proper, one sees sights so gruesome that none but the soulless Hungarian and Italian laborers can command his emotions.

“At my right is a fiery pit that is now believed to have been the funeral pyre of almost a thousand persons.”

Streets Obliterated

The fiercest rush of the current was straight across the lower, level part of Johnstown, where it entirely obliterated Cinder, Washington, Market, Main and Walnut streets. These streets were from a half to three-quarters of a mile in length, and were closely crowded along their entire course with dwellings and other buildings, and there is now no more trace of streets or houses than there is at low tide on the beach at Far Rockaway.

In the once well populated boroughs of Conemaugh and Woodvale there are to-night literally but two buildings left, one the shell of the Woodvale Woolen Mill and the other a sturdy brick dwelling.

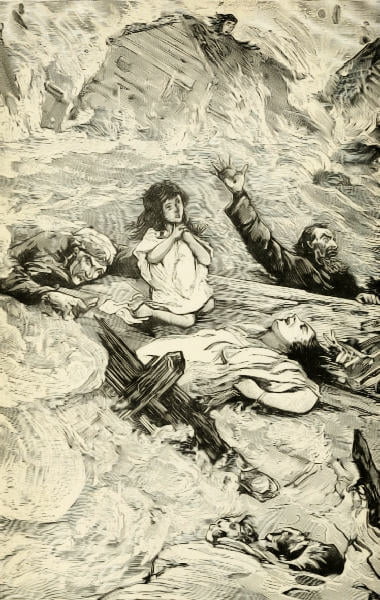

The buildings which were swept from twenty out of the thirty acres of devastated Johnstown were crowded against the lower end of the big stone bridge in a mass 200 yards wide, 500 yards broad and from 60 to 100 feet deep. They were crushed and split out of shape and packed together like playing cards.

When you realize that in nearly every one of these buildings there were at least one human being, while in some there were as many as seventy-five, it is easy to comprehend how awful it was when this mass began to burn fiercely last night. It was known that a large number of persons were imprisoned in the débris, for they could be plainly seen by those on shore, but it was not until people stopped to think and to ask themselves questions, which startled them in a ghastly way, that the fact became plain that instead of a pitiful hundred or two of victims at least a thousand were in that roaring, crackling, loathsome, blazing mass upon the surface of the water and in the huge, inaccessible arches of the big bridge.

Charred Bodies

Charred bodies could be seen here and there all through the glowing embers. There was no attempt to check the fire by the authorities, nor for that matter did they try to stop the robbing of the dead, nor any other glaring violation of law. The fire is spreading toward a large block of crushed buildings further up the stream. There is a broad stretch of angry water above and below, while over there, just opposite the end of the bridge, is the ruin of the great Cambria Iron Works, which have been damaged to the extent of over $1,000,000.

The Gautier Steel Works have been wiped away, and are represented by a loss of $1,000,000 and a big hole.

The Holbert House, owned by Renford Brothers, has entirely disappeared. It was a five story building, was the leading hotel of Johnstown, and contained a hundred rooms. Of the seventy-five guests who were in it when the flood came, only eight have been saved. Most of them were crushed by the fall of the walls and flooring.

Hundreds of searching parties are looking in the muddy ponds and among the wreckage for bodies and they are being gathered in ghastly heaps.

In one building among the bloated victims, I saw a young and well-dressed man and woman, still locked in each other’s arms, a young mother with her babe pressed with delirious tenacity to her breast, and on a small pillow was a tiny babe a few hours old, which the doctors said must have been born in the water. It is said that 720 bodies have so far been recovered, or have been located.

The coroner of Westmoreland county is ordering coffins by the carload.

In the Raging Waters

A dispatch from Derry says: In this city the poor people in the raging waters cried out for aid that never came. More than one brave man risked his life in trying to save those in the flood. Every hour details of some heroic action are brought to light. In many instances the victims displayed remarkable courage and gave their chances for rescue to friends with them. Sons stood back for mothers, and were lost while their parents were taken out. Many a son went down to a watery grave that a sister or a father might be saved. Such instances of sacrifice in the face of fearful danger are numerous.

The Force of the Waters

One can estimate the force of the water when it is known that it carried locomotives down the mountain side and turned them upside down where they are now lying. Long trains of cars have been derailed and carried great distances from the railroads.

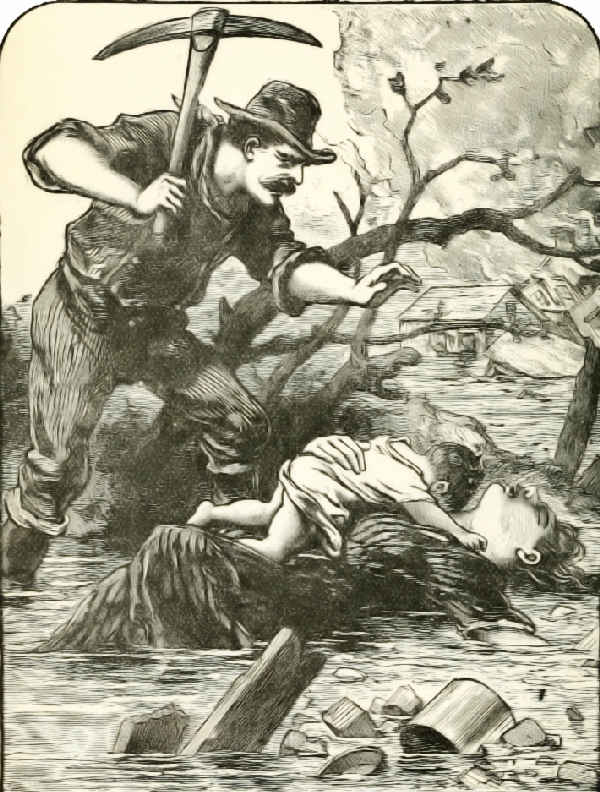

The first sight that greeted the men at nine this morning was the body of a beautiful woman lying crushed and mangled under the ponderous wheels of a gondola car. The clothing was torn to shreds. Dr. Berry said that he never saw such intense pain pictured on a face before.

Terrible Stories

At this time of writing it is impossible to secure the names of any of the lost. Every person one meets along the road has some horrible tale of drowned and dead bodies recovered.

One thousand people or more were buried and crushed in the great fire. The flats below Conemaugh are full of cars with many dead bodies lying under them. At Sang Hollow a man named Duncan sat on the roof of a house and saw his father and mother die in the attic below him. The poor fellow was powerless to help them, and he stood there wringing his hands and tearing his hair.

A man was seen clinging to a tree, covered with blood. He was lost with the others.

Long after dark the flames of fire shot high above the burning mass of timber, lighting the vast flood of rushing waters on all sides.

The Dead

Dead bodies are being picked up. The train master, E. Pitcairn, has been working manfully directing the rescuing of dead bodies at Nineveh. In a ten acre field seventy-five bodies were taken out within a half mile of each other. Of this number only five were men, the rest being women and children. Many beautiful young girls, refined in features and handsomely dressed, were found, and women and young mothers with their hair matted with roots and leaves are constantly being removed.

The wrecking crew which took out these bodies are confident that 150 bodies are lying buried in the sand and under the débris on those low-lying bottom lands. Some of the bodies were horribly mangled, and the features were twisted and contorted as if they had died in the most excrutiating agony. Others are found lying stretched out with calm faces.

Many a tear was dropped by the men as they worked away removing the bodies. An old lady with fine gray hair was picked up alive, although every bone in her body was broken. Judging from the number of women and children found in the swamps of Nineveh, the female portion of the population suffered the most.

A Fatal Tree

Mr. O’Conner was at Sang Hollow when the flood began. He remained there through the afternoon and night, and he states that there was a fatal tree on the island against which a number of people were dashed and instantly killed. Their bodies were almost tied in a knot doubled over the tree by the force of the current. Mr. O’Conner says that the first man who came down had his brains knocked out against this obstruction. In fact, those who hit the tree met the same fate and were instantly killed under the pile of driftwood collected there. He could give no estimate of the number lost at this point, but says that it is certainly large.

Braves Death for His Family

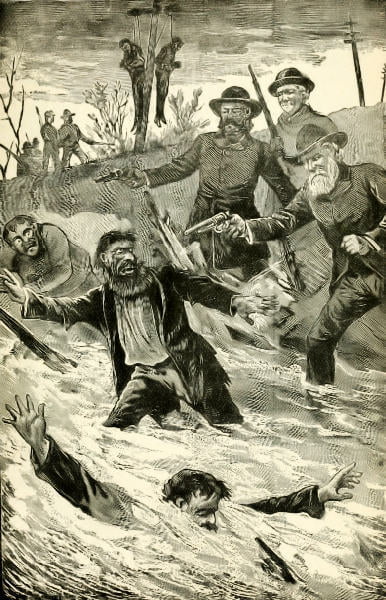

One of the most thrilling incidents of the disaster was the performance of A.J. Leonard, whose family reside in Morrellville, a short distance below this point. He was at work here, and hearing that his house had been swept away determined at all hazards to ascertain the fate of his family. The bridges having been carried away he constructed a temporary raft, and clinging to it as close as a cat to the side of a fence, he pushed his frail craft out in the raging torrent and started on a chase which, to all who were watching, seemed to mean an embrace in death.

Heedless of cries “For God’s sake go back, you will be drowned,” and “Don’t attempt it,” he persevered. As the raft struck the current he threw off his coat and in his shirt sleeves braved the stream. Down plunged the boards and down went Leonard, but as it rose he was seen still clinging. A mighty shout arose from the throats of the hundreds on the banks, who were now deeply interested, earnestly hoping he would successfully ford the stream.

Down again went his bark, but nothing, it seemed, could shake Leonard off. The craft shot up in the air apparently ten or twelve feet, and Leonard stuck to it tenaciously. Slowly but surely he worked his boat to the other side of the stream, and after what seemed an awful suspense he finally landed amid ringing cheers of men, women and children.

The last seen of him he was making his way down a mountain road in the direction of the spot where his house had lately stood. His family consisted of his wife and three children.

An Angel in the Mud

The Pennsylvania Railroad Company’s operators at Switch Corner, which is near Sang Hollow, tell thrilling stories of the scenes witnessed by them on Friday afternoon and evening. Said one of them:

“In order to give you an idea of how the tidal wave rose and fell, let me say that I kept a measure and timed the rise and fall of the water, and in forty-eight minutes it fell four and a half feet.

“I believe that when the water goes down about seventy-five children and fifty grown persons will be found among the weeds and bushes in the bend of the river just below the tower.

“There the current was very strong, and we saw dozens of people swept under the trees, and I don’t believe that more than one in twenty came out on the other side.”

“They found a little girl in white just now,” said one of the other operators.

“Good God!” said the chief operator, “she isn’t dead, is she!”

“Yes; they found her in a clump of willow bushes, kneeling on a board, just about the way we saw her when she went down the river.” Turning to me he said:–

“That was the saddest thing we saw all day yesterday. Two men came down on a little raft, with a little girl kneeling between them, and her hands raised and praying. She came so close to us we could see her face, and that she was crying. She had on a white dress and looked like a little angel. She went under that cursed shoot in the willow bushes at the bend like all the rest, but we did hope she would get through alive.”

“And so she was still kneeling,” he said to his companion, who had brought the unwelcome news.

“She sat there,” was the reply, “as if she were still praying, and there was a smile on her poor little face, though her mouth was full of mud.”

All agreed in saying that at least one hundred people were drowned below Nineveh.

Direful Incidents

The situation at Johnstown grows worse as fuller particulars are being received in Pittsburgh.

This morning it was reported that three thousand people were lost in the flood. In the afternoon this number was increased to six thousand, and at this writing despatches place the number at ten thousand.

It is the most frightful destruction of life that has ever been known in the United States.

Vampires at Hand

It is stated that already a large gang of thieves and vampires have descended on and near the place. Their presumed purpose is to rob the dead and ransack the demolished buildings.

The Tenth regiment of the Pennsylvania National Guard has been ordered out to protect property.

A telegram from Bolivar says Lockport did not suffer much, but that sixty-five families were turned out of their homes. The school at that place is filled with mothers, fathers, daughters and children.

Noble Acts of Heroism

Edward Dick, a young railroader living in the place, saw an old man floating down the river on a tree trunk whose agonized face and streaming gray hair excited his compassion. He plunged into the torrent, clothes and all, and brought the old man safely ashore. Scarcely had he done this when the upper story of a house floated by on which Mrs. Adams, of Cambria, and her two children were borne. He plunged in again, and while breaking through the tin roof of the house cut an artery in his left wrist, but, although weakened with loss of blood, succeeded in saving both mother and children.

George Shore, another Lockport swimmer, pulled out William Jones, of Cambria, who was almost exhausted and could not possibly have survived another twenty minutes in the water.

John Decker, who has some celebrity as a local pugilist, was also successful in saving a woman and boy, but was nearly killed in a third attempt to reach the middle of the river by being struck by a huge log.

The most miraculous fact about the people who reached Bolivar alive was how they passed through the falls halfway between Lockport and Bolivar. The seething waters rushed through that barrier of rock with a noise which drowned that of all the passing trains. Heavy trees were whirled high in the air out of the water, and houses which reached there whole were dashed to splinters against the rocks.

A Tale of Horror

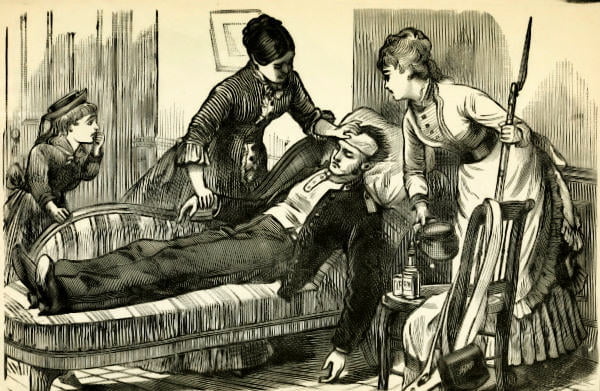

On the floor of William Mancarro’s house, groaning with pain and grief, lay Patrick Madden, a furnace man of the Cambria Iron Company. He told of his terrible experience in a voice broken with emotion. He said: “When the Cambria Iron Company’s bridge gave way I was in the house of a neighbor, Edward Garvey. We were caught through our own neglect, like a great many others, and a few minutes before the houses were struck Garvey remarked that he was a good swimmer, and could get away no matter how high the water rose. Ten minutes later I saw him and his son-in-law drowned.

“No human being could swim in that terrible torrent of débris. After the South Fork reservoir broke I was flung out of the building and saw, when I rose to the surface of the water, my wife hanging upon a piece of scantling. She let it go and was drowned almost within reach of my arm and I could not help or save her. I caught a log and floated with it five or six miles, but it was knocked from under me when I went over the dam. I then caught a bale of hay and was taken out by Mr. Morenrow.”

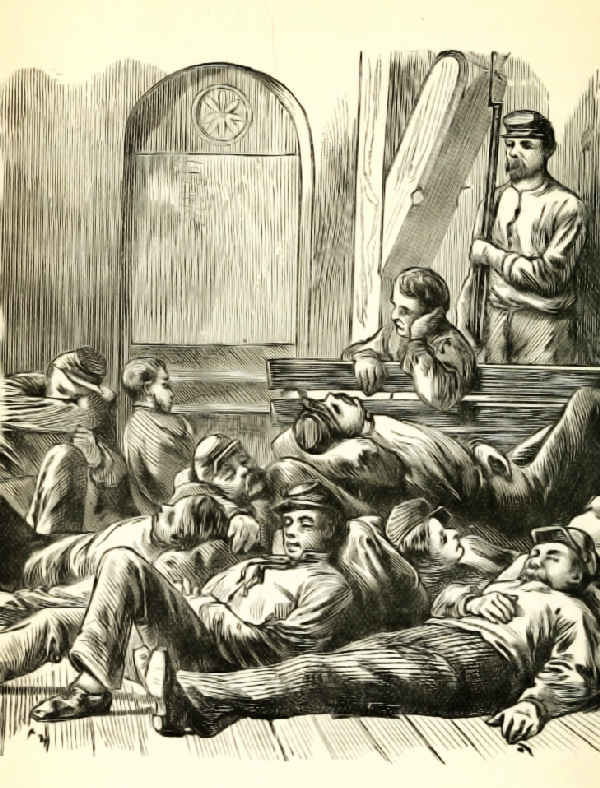

A despatch from Greensburg says the day express, which left Pittsburgh at eight o’clock on Friday morning was lying at Johnstown in the evening at the time the awful rush of waters came down the mountains. We have been informed by one who was there that the coach next to the baggage car was struck by the raging flood, and with its human freight cut loose from the rest of the train and carried down the stream. All on board, it is feared, perished. Of the passengers who were left on the track, fifteen or more who endeavored to flee to the mountains were caught, it is thought, by the flood, and likewise carried to destruction. Samuel Bell, of Latrobe, was conductor on the train, and he describes the scene as the most appalling and heartrending he ever witnessed.

A special despatch from Latrobe says:–“The special train which left the Union Station, Pittsburgh, at half-past one arrived at Nineveh Station, nine miles from Johnstown, last evening at five o’clock. The train was composed of four coaches and locomotive, and carried, at the lowest calculation, over nine hundred persons, including the members of the press. The passengers were packed in like sardines and many were compelled to hang out upon the platform. A large proportion of the passengers were curiosity seekers, while there was a large sprinkling of suspicious looking characters, who had every appearance of being crooks and wreckers, such as visit all like disasters for the sole purpose of plundering and committing kindred depredations.”

When the train reached Nineveh the report spread through it that a number of bodies had been fished out of the water and were awaiting identification at a neighboring planing mill. I stopped off to investigate the rumor, while the balance of the party journeyed on toward Sang Hollow, the nearest approach to Johnstown by rail. I visited Mumaker’s planing mills and found that the report was true.

All day long the rescuers had been at work, and at this writing (six o’clock) they have taken out seventy-eight dead bodies, the majority of whom are women and children. The bodies are horribly mutilated and covered with mud and blood. Fifteen of them are those of men. Their terribly mutilated condition makes identification for the present almost impossible. One of the bodies found was that of a woman, apparently about thirty-five years of age.

Every conveyance that could be used has been pressed into service. Latrobe is all agog with excitement over the great disaster. Almost every train takes out a load of roughs and thugs who are bent on mischief. They resemble the mob that came to Pittsburgh during the riots.

Measures of Relief

Pittsburgh is in a wild state of excitement. A large mass meeting was held yesterday afternoon and in a short space of time $1,000 was subscribed for the sufferers.

The Pennsylvania company has been running trains every hour to the scene of the disaster or as near it as they can get. Provisions and a large volunteer relief corps have been sent up. The physicians have had an enthusiastic meeting at which one and all freely offered their services.

The latest project is to have the wounded and the survivors who fled to the hillsides from the angry rush of waters brought to Pittsburgh. The Exposition Society has offered the use of its splendid new building as a temporary hospital. All the hospitals in the city have also offered to care for the sufferers free of charge to the full limit of their capacity.

Word has been received at Allegheny Junction, twenty-two miles above Pittsburgh, from Leechburg that a woman and two children were seen floating past there at five o’clock yesterday morning on top of some wreckage. They were alive, and their pitiful cries for help drew the attention of the people on the shore. Some men got a boat and endeavored to reach the sufferers.

As they rowed out in the stream the woman could be heard calling to them to save the children first.

The men made a gallant effort. It was all without avail, as the strong current and floating masses of débris prevented them from reaching the victims, and the latter floated on down the stream until their despairing cries could no longer be heard.

Mrs. Chambers, of Apollo, was swept away when her house was wrecked during the night. She had gone to bed when the flood came and she had not time to dress. Fortunately she managed to secure a hold on some wreckage which was being carried past her. She kept her hold until her cries were heard by some men a short distance above Leechburg. They got out a boat and succeeded in reaching her, and took her to a house near the bank of the river. When they got her there it was found that she was badly bruised and all her clothing had been torn off by the débris with which she had come in contact, leaving her entirely naked. She was also rescued at Natrona.

A Lucky Change of Residence

Mr. F.J. Moore, of the Western Union office in this city, is giving thanks to-day for the fortunate escape of his wife and two children from the devastated city. As if by some foreknowledge of the impending disaster, Mr. Moore had arranged to have his family move yesterday from Johnstown and join him in this city. Their household goods were shipped on Thursday, and yesterday just in time to save themselves, the little party departed in the single train which made the trip between Johnstown and Pittsburgh. I called on Mrs. Moore at her husband’s apartments, No. 4 Webster avenue, and found her completely prostrated by the news of the final catastrophe, coupled with the dangerous experience through which she and her little ones had passed.

“Oh, it was terrible,” she said. “The reservoir had broken, and before we got out of the house the water filled the cellar, and on the way to the depot it was up to the carriage bed. Our train left at a quarter to two P.M., and at that hour the flood had commenced to rise with terrible rapidity. Houses and sheds were carried away, and two men were drowned almost under our very eyes. People gathered on the roofs to take refuge from the water which poured into the lower rooms of their dwellings, and many families took fright and became scattered beyond hope of being reunited. Just as the train pulled out I saw a woman crying bitterly. Her house had been flooded and she had escaped, leaving her husband behind, and her fears for his safety made her almost crazy. Our house was in the lower part of the town, and it makes me shudder to think what would have happened had we remained in it an hour longer. So far as I know we were the only passengers from Johnstown on the train, and therefore I suppose we are the only persons who got away in time to escape the culminating disaster.”

Mrs. Moore’s little son told me how he had seen the rats driven out of their holes by the flood and running along the tops of the fences. Mr. Moore endeavored to get to Johnstown yesterday, but was prevented by the suspension of traffic and says he is very glad of it.

What the Eye Hath Seen

The scenes at Heanemyer’s planing mill at Nineveh, where the dead bodies are lying, are never to be forgotten. The torn, bruised and mutilated bodies of the victims are lying in a row on the floor of the planing mill which looks more like the field of Bull Run after that disastrous battle than a work shop. The majority of the bodies are nude, their clothing having been torn off. All along the river bits of clothing–a tiny shoe, a baby dress, a mother’s evening wrapper, a father’s coat, and in fact every article of wearing apparel imaginable may be seen hanging to stumps of trees and scattered on the bank.

One of the most pitiful sights of this terrible disaster came to my notice this afternoon when the body of a young lady was taken out of the Conemaugh River. The woman was apparently quite young, though her features were terribly disfigured. Nearly all the clothing excepting the shoes was torn off the body. The corpse was that of a mother, for although cold in death she clasped a young male babe, apparently not more than a year old, tightly in her arms. The little one was huddled close up to the face of the mother, who when she realized their terrible fate had evidently raised it to her lips to imprint upon its lips the last kiss it was to receive in this world. The sight forced many a stout heart to shed tears. The limp bodies, with matted hair, some with holes in their heads, eyes knocked out and all bespattered with blood were a ghastly spectacle.

Story of The First Fugitives

The first survivors of the Johnstown wreck who arrived in the city last night were Joseph and Henry Lauffer and Lew Dalmeyer, three well known Pittsburghers. They endured considerable hardship and had several narrow escapes with their lives. Their story of the disaster can best be told in their own language. Joe, the youngest of the Lauffer brothers, said:–

“My brother and I left on Thursday for Johnstown. The night we arrived there it rained continually, and on Friday morning it began to flood. I started for the Cambria store at a quarter past eight on Friday, and in fifteen minutes afterward I had to get out of the store in a wagon, the water was running so rapidly. We then arrived at the station and took the day express and went as far as Conemaugh, where we had to stop. The limited, however got through, and just as we were about to start the bridge at South Fork gave way with a terrific crash, and we had to stay there. We then went to Johnstown. This was at a quarter to ten in the morning, when the flood was just beginning. The whole city of Johnstown was inundated and the people all moved up to the second floor.

Mountains of Water

“Now this is where the trouble occurred. These poor unfortunates did not know the reservoir would burst, and there are no skiffs in Johnstown to escape in. When the South Fork basin gave way mountains of water twenty feet high came rushing down the Conemaugh River, carrying before them death and destruction. I shall never forget the harrowing scene. Just think of it! thousands of people, men, women and children, struggling and weeping and wailing as they were being carried suddenly away in the raging current. Houses were picked up as if they were but a feather, and their inmates were all carried away with them, while cries of ‘God help me!’ ‘Save me!’ ‘I am drowning!’ ‘My child!’ and the like were heard on all sides. Those who were lucky enough to escape went to the mountains, and there they beheld the poor unfortunates being crushed among the débris to death without any chance of being rescued. Here and there a body was seen to make a wild leap into the air and then sink to the bottom.

“At the stone bridge of the Pennsylvania company people were dashed to death against the piers. When the fire started there hundreds of bodies were burned. Many lookers-on up on the mountains, especially the women, fainted.”

Mr. Lauffer’s brother, Harry, then told his part of the tale, which was not less interesting. He said:–“We had the most narrow escapes of anybody, and I tell you we don’t want to be around when anything of that kind occurs again.

“The scenes at Johnstown have not in the least been exaggerated, and indeed the worst is to be heard. When we got to Conemaugh and just as we were about to start the bridge gave way. This left the day express, the accommodation, a special train and a freight train at the station. Above was the South Fork water basin, and all of the trains were well filled. We were discussing the situation when suddenly, without any warning, the whistles of every engine began to shriek, and in the noise could be heard the warning of the first engineer, ‘My God! Rush to the mountains, the reservoir has burst.’ Then, with a thundering like peal came the mad rush of waters. No sooner had the cry been heard than those who could with a wild leap rushed from the train and up the mountains. To tell this story takes some time, but the moments in which the horrible scene was enacted were few. Then came the tornado of water, leaping and rushing with tremendous force. The waves had angry crests of white and their roar was something deafening. In one terrible swath they caught the four trains and lifted three of them right off the track, as if they were only a cork. There they floated in the river. Think of it, three large locomotives and finely varnished Pullmans floating around, and above all the hundreds of poor unfortunates who were unable to escape from the car swiftly drifting toward death. Just as we were about to leap from the car I saw a mother, with a smiling, blue eyed baby in her arms. I snatched it from her and leaped from the train just as it was lifted off of the track. The mother and child were saved, but if one more minute had elapsed we all would have perished.”

Beyond the Power of Words

During all of this time the waters kept rushing down the Conemaugh and through the beautiful town of Johnstown, picking up everything and sparing nothing.

The mountains by this time were black with people, and the moans and sighs from those below brought tears to the eyes of the most stony hearted. There in that terrible rampage were brothers, sisters, wives and husbands, and from the mountain could be seen the panic stricken marks in the faces of those who were struggling between life and death. I really am unable to do justice to the scene, and its details are almost beyond my power to relate. Then came the burning of the débris near the Pennsylvania Railroad bridge. The scene was too sickening to endure. We left the spot and journeyed across country and delivered many notes, letters, etc., that were intrusted to us.

We rode thirty-one miles in a buckboard, then walked six miles, reached Blairsville and journeyed again on foot to what is called the “Bow,” and from thence we arrived home. On our way we met Mr. F. Thompson, a friend of ours, who resides in Nineveh, and he stated that rescuing parties were busy all day at Annom. One hundred and seventy-five bodies were recovered at that place. An old couple about sixty years of age were rescued from a tree, on which they came floating down the stream. They were clasped in each other’s arms.

President Harrison’s private secretary, Elijah Halford, and wife, were on the train which was swept away, but escaped and were in the mountains when I left.

Among the lost are Colonel John P. Linton and his wife and children. Colonel Linton was prominent in the Grand Army of the Republic and in the Knights of Pythias and other orders. He was formerly Auditor General of Pennsylvania.