It would be interesting to know who were the occupants of the Pike’s Peak region during prehistoric times. Were its inhabitants always nomadic Indians? We know that semi-civilized peoples inhabited southwestern Colorado and New Mexico in prehistoric times, who undoubtedly had lived there ages before they were driven into cliff dwellings and communal houses by savage invaders. Did their frontier settlements of that period ever extend into the Pike’s Peak region? The facts concerning these matters, we may never know. As it is, the earliest definite information we have concerning the occupants of this region dates from the Spanish exploring expeditions, but even that is very meager. From this and other sources, we know that a succession of Indian tribes moved southward along the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains during the two hundred years before the coming of the white settler, and that during this period, the principal tribes occupying this region were the Ute, Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux; and, further, that there were other tribes such as the Pawnees and Jicarilla Apache, who frequently visited and hunted in this region.

Jicarilla Apache Indians of Colorado

The Jicarilla Apaches are of the Athapascan stock, a widely distributed linguistic family, which includes among its branches the Navajos, the Mescalaro of New Mexico, and the Apaches of Arizona. Notwithstanding the fact that they were kindred people, the Jicarilla considered the latter tribes their enemies. However, they always maintained friendly relations with the Ute, and the Pueblos of northern New Mexico, and inter-marriages between members of these tribes were of frequent occurrence. The mother of Ouray, the noted Ute chief, was a Jicarilla Apache.

From the earliest period, the principal home of the Jicarilla Apaches was along the Rio Grande River in northern New Mexico, but in their wanderings they often went north of the Arkansas River and far out on the plains, where they had an outpost known as the Quartelejo. By reason of the intimate relations existing between the Jicarilla and the Pueblo Indians, this outpost was more than once used as a place of refuge by members of the latter tribes. Bancroft, in his history of New Mexico, says that certain families of Taos Indians went out into the plains about the middle of the seventeenth century and fortified a place called “Cuartalejo,” which undoubtedly is but another spelling of the name Quartelejo. These people remained at Quartelejo for many years, but finally returned to Taos at the solicitation of an agent sent out by the Government of New Mexico. In 1704, the Picuris, another Pueblo tribe, whose home was about forty miles north of Sante Fe, abandoned their village in a body and fled to Quartelejo, but they also returned to New Mexico two years later. Quartelejo is frequently mentioned in the history of New Mexico, and its location is described as being 130 leagues northeast of Santa Fe. In recent years the ruin of a typical Pueblo structure has been unearthed on Beaver Creek in Scott County, Kansas, about two hundred miles east of Colorado Springs, which, in direction and distance from Santa Fe, coincides with the description given of Quartelejo, and is generally believed to be that place.

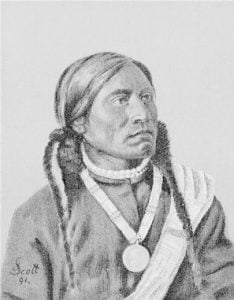

Ute Indians of Colorado

Aside from the Jicarilla Apaches, the Ute, living in the mountainous portion of the region now included in the State of Colorado, were the earliest occupants of whom there is any historical account. They were mentioned in the Spanish records of New Mexico as already inhabiting the region to the north of that Territory in the early part of the seventeenth century. At that time, and for many years afterward, they were on peaceable terms with the Spanish settlers of New Mexico. About 1705, however, something occurred to disturb their friendly relations, and a war resulted which lasted fifteen to twenty years, during which time many people were killed, numerous ranches were plundered, and many horses stolen. Although the Ute already owned many horses, it is said that in these raids they acquired so many more that they were able to mount their entire tribe. During that time various military expeditions were sent against the Ute as well as against the Comanche, who had first appeared in New Mexico in 1716. In 1719, the Governor of New Mexico led a military force, consisting of 105 Spaniards and a large number of Indian auxiliaries, into the region which is now the State of Colorado, against the hostile bands. The record of the expedition says that it left Santa Fe on September 15th and marched north, with the mountains on the left, until October 10th. In this twenty-five days’ march the expedition should have gone far beyond the place where Colorado Springs now stands. Although the expedition failed to overtake the Indians, the latter ceased their raids for a time, but their subsequent outbreaks showed that their friendship for the New Mexican people could not be entirely depended upon, although they mingled with them to such an extent that a large portion of the tribe acquired a fair knowledge of the Spanish language.

The Ute were an offshoot of the Shoshone family, the branches of which have been widely distributed over the Rocky Mountain region from the Canadian line south into Mexico. It is now generally conceded that the Aztecs of Mexico and the Ute belong to the same linguistic family. It is probable that in the march of the former toward the south, many centuries ago, the Ute were left behind, remaining in their savage state, while the Aztecs, coming in contact with the semi-civilized nations of the South, gradually reached the state of culture which they had attained at the time of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. I am firmly of the opinion that these Indians, and in fact all the Indians of America, are descendants of Asiatic tribes that crossed over to this continent by way of Bering Strait at some remote period. These tribes may, however, have been added to at various times by chance migrations from Japan, the Hawaiian and South Sea islands. It is known that in historic times the Japanese current has thrown upon the Pacific Coast fishing-boats, laden with Japanese people, which had drifted helplessly across the Pacific Ocean. It is, therefore, fair to assume that what is known to have occurred in recent times might also have frequently occurred in the remote past, and if this be so, the intermarriage of these people with the native races would undoubtedly have had a decided influence upon the tribes adjacent to the Pacific Coast. There seems to be no reason why the people of the Hawaiian Islands should not have visited our shores, as those islands are not much farther distant from the Pacific Coast than are certain inhabited islands in other directions. These same conclusions have been reached by many others who have made a study of the question.

The National Geographic Magazine of April, 1910, contained an article written by Miss Scidmore on “Mukden, the Manchu Home,” in which she says:

When I saw the Viceroy and his suite at a Japanese fete at Tairen, whither he had gone to pay a state visit, I was convinced as never before of the common origin of the North American Indian and the Chinese or Manchu Tartars. There before me might as well have been Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, and Rain-in-the-Face, dressed in blue satin blankets, thick-soled moccasins, and squat war-bonnets with single bunches of feathers shooting back from the crown. Manchu eyes, Tartar cheekbones, and Mongol jaws were combined in countenances that any Sioux chief would recognize as a brother.

The Ute Indians were well-built, but not nearly as tall as the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, or any of the tribes of the plains. Their type of countenance was substantially the same as that of all American Indians. They were distinctly mountain Indians, and that they should have been a shorter race than those of the plains to the east is peculiar, as it reverses the usual rule. Might not this have been the result of an infusion of Japanese blood in the early days of the Shoshones when their numbers were small? And possibly from this same source came the unusual ability of the Ute in warfare.

As Indians go, the Ute were a fairly intelligent people. They had a less vicious look than the Indians of the plains, and as far as my observation goes, they were not so cruel. They ranged over the mountainous region from the northern boundaries of the present State of Colorado, down as far as the central part of New Mexico. Their favorite camping-place, however, was in the beautiful valleys of the South Park, and other places in the region west of Pike’s Peak. The South Park was known to the old trappers and hunters as the Bayou Salado, probably deriving its name from the salt marshes and springs that were abundant in the western part of that locality.

Game was to be found in greater abundance in the South Park and the country round about than in almost any other region of the Rocky Mountains, and for that reason its possession was contended for most strenuously year after year by all the tribes of the surrounding country. For a time in the summer season, the Ute were frequently driven away from this favorite region by the tribes of the plains who congregated in the South Park in great numbers as soon as the heat of the plains became uncomfortable. However, the Ute seldom failed to retain possession during most of the year, as they were remarkably good fighters and more than able to hold their own against equal numbers.

Comanche Indians of Colorado

In point of time, the Comanche were the next tribe of which we have any record, as inhabiting this region. These Indians also were a branch of the Shoshone nation. They led the procession of tribes that moved southward along the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains during the seventeenth and the first half of the eighteenth centuries. When first heard of, they were occupying the territory where the Missouri River emerges from the Rocky Mountains. Later, they were driven south by the pressure of the Sioux Indians and other tribes coming in from the north and east. For a while they occupied the Black Hills, and then were pushed still farther south by the Kiowa. They joined their kinsmen the Ute in raids upon the settlements of New Mexico in 1716, and it was to punish the Comanche as well as the Ute, that the Governor of New Mexico, in 1719, led the military expedition into the country now within the boundaries of Colorado. In 1724, Bourgemont, a French explorer mentions them under the name of the Padouca, as located between the headwaters of the Platte and Kansas rivers, but later accounts show that before the end of that century they had been pushed south of the Arkansas River by the pressure of the tribes to the north.

During the stay of the Comanche in this region, they were for a time friendly with the Ute, and the two tribes joined each other in warfare and roamed over much of the same territory, but later, for some unknown reason, they for a time engaged in a deadly warfare. The old legend of the Manitou Springs mentions the possible beginning of the trouble. The incident around which the legend is woven, may be an imaginary one, but it is a well-known fact that long and bitter wars between tribes resulted from slighter causes. It is said that a long war between the Delaware and Shawnees originated in a quarrel between two children over a grasshopper.

The Comanche were a nation of daring warriors, and after their removal to the south of the Arkansas River, they became a great scourge to the settlements of Texas and New Mexico, finally extending their raids as far as Chihuahua, in Mexico. As a result of these operations, they became rich in horses and plunder obtained in their raids, besides securing as captives many American and Spanish women and children. One of their most noted chiefs in after days was the son of a white woman who had been captured in Texas in her childhood, and who, when grown, had married a Comanche chief. The Government arranged for the release of both the American and Spanish captives, but in more than one instance women who had been captured in their younger days refused to leave their Comanche husbands, notwithstanding the strongest urging on the part of their own parents.

Kiowa Indians of Colorado

Following the Comanche came the Kiowa, a tribe of unknown origin, as their language seems to have no similarity to that of any of the other tribes of this country. According to their mythology, their first progenitors emerged from a hollow cottonwood log, at the bidding of a supernatural ancestor. They came out one at a time as he tapped upon the log, until it came to the turn of a fleshy woman, who stuck fast in the hole, and thus blocked the way for those behind her, so that they were unable to follow. This they say, accounts for the small number of the Kiowa tribe.

The first mention of this tribe locates them at the extreme sources of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers, in what is now central Montana. Later, by permission of the Crow Indians, they took up their residence east of that tribe and became allied with them. Up to this time they possessed no horses and in moving about had to depend solely upon dogs. They finally drifted out upon the plains; here they first procured horses, and came in contact with the Arapahoe, Cheyenne, and, later, with the Sioux. The tribe probably secured horses by raids upon the Spaniards of New Mexico, as the authorities of that Territory mention the Kiowa as early as 1748, while the latter were still living in the Black Hills. It may not be generally known that there were no horses upon the American continent prior to the coming of the Spaniards. The first horses acquired by the Indians were those lost or abandoned by the early exploring expeditions, and these were added to later by raids upon the Spanish settlements of New Mexico. The natural increase of the horses so obtained gave the Indians, in many cases, a number in excess of their needs. Previous to acquiring horses, the Indians used dogs in moving their belongings around the country. As compared with their swift movements of later days this slow method of transportation very materially limited their migrations.

By the end of that century, the Kiowa had drifted south into the region embraced by the present State of Colorado, probably being forced to do so by the pressure of the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who were at that time advancing from the north and east. As the Kiowa advanced southward, they encountered the Comanche; this resulted in warfare that lasted many years, in the course of which the Comanche were gradually driven south of the Arkansas River. When, finally, the war was terminated, an alliance was effected between the two tribes, which thereafter remained unbroken. In 1806, the Kiowa were occupying the country along the eastern base of the mountains of the Pike’s Peak region. From Lieut. Zebulon Pike’s narrative, we learn that James Pursley, who, according to Lieutenant Pike, was the first American to penetrate the immense wilds of Louisiana, spent a trading season with the Kiowa and Comanche in 1802 and 1803. He remained with them until the next spring, when the Sioux drove them from the plains into the mountains at the head of the Platte and Arkansas rivers. In all probability their retreat into the mountains was through Ute Pass, as that was the most accessible route. In the same statement Lieutenant Pike mentions Pursley’s claim to having found gold on the headwaters of the Platte River. By the year 1815, most of the Kiowa had been pushed south of the Arkansas River by the Cheyenne and Arapaho, but not until 1840 did they finally give up fighting for the possession of this region.

Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians of Colorado

The Cheyenne and Arapaho were of the Algonquin linguistic family, whose original home was in the New England States and southern Canada. When first heard of, about 1750, the Cheyenne were located in northern Minnesota. Later, about 1790, they were living on the Missouri, near the mouth of the Cheyenne River. Subsequently they moved west into the Black Hills, being forced to do so by the enmity of the Sioux. Here they were joined by the Arapaho, a tribe of the same Algonquin stock, and from that time on the two tribes were bound together in the closest relations.

Beginning about 1800, these two federated tribes, accompanied by some of the Sioux, with whom they had made peace, gradually moved southward along the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains. Dr. James, the historian of Long’s expedition which visited the Pike’s Peak region in 182o, mentions the fact that about four years previous there had been a large encampment of Indians on a stream near Platte Canon, southwest of Denver, which had assembled for trading purposes. It appears that the Cheyenne had been supplied with goods by British traders on the Missouri River, and had met to exchange these goods for horses. The tribes dwelling on the fertile plains of the Arkansas and Red rivers always had a great number of horses, which they reared with much less difficulty than did the Cheyenne, who usually spent the winter in the country farther to the north, where the cold weather lasted much longer and feed was less abundant. After many years of warfare with the Kiowa, the Cheyenne and Arapaho were victorious, and by a treaty, made in 1840, secured undisputed possession of the territory north of the Arkansas River and east of the mountains. As this was only eighteen years before the coming of the whites, the Cheyenne and Arapaho could not rightfully claim this region as their ancestral home. The country acquired by the Cheyenne and Arapaho, through their victory over the Kiowa, embraced a territory of more than eighty thousand square miles. As in those two tribes there were never more than five thousand men, women, and children, all told, the area was out of all proportion to their numbers.

Early in 1861, the Government made a treaty (Treaty of February 18, 1861) with the Cheyenne and Arapaho by which these tribes gave up the greater part of the lands claimed by them in the new Territory of Colorado. For this they were to receive a consideration of four hundred and fifty thousand dollars, to be paid in fifteen yearly installments, the tribes reserving for their own use a tract about seventy miles square located on both sides of the Arkansas River in the southeastern part of the Territory.

From the time of their first contact with the whites, the Cheyenne and Arapaho were alternately friendly or hostile, just as their temper or whim dictated upon any particular occasion. With the old trappers and hunters of the plains, the Cheyenne had the reputation of being the most treacherous and untrustworthy at all times and in all places, of any of the tribes of the West. The Arapaho, while occasionally committing depredations against the whites, were said to be somewhat different in temperament, in that they were not so sullen and morose as the Cheyenne, and were less treacherous and more open and trustworthy in their dealings. This estimate of the characteristics of the two tribes was fully confirmed in our contact with them in the early days of Colorado.

The Cheyenne were continuously hostile during the years 1855, 1856, and 1857, killing many whites and robbing numerous wagon-trains along the Platte River, which at that time was the great thoroughfare for travelers to Utah, California, Oregon, and other regions to the west of the Rocky Mountains. In 1857, the Cheyenne were severely punished in a number of engagements by troops under command of Colonel E. V. Sumner of the regular army, and as a result, they gave little trouble during the next five or six years.

In the early days, the Arapaho came in touch with the whites to a much greater extent than did the Cheyenne. The members of the latter tribe usually held aloof, and by their manner plainly expressed hatred of the white race. Horace Greeley, in his book describing his trip across the plains to California in 1859, tells of a large body of Arapaho who were encamped on the outskirts of Denver in June of that year, because of the protection they thought it gave them from their enemies the Ute. I saw this band when I passed through Denver in June of the following year.

Sioux Indians of Colorado

The Sioux were one of the largest Indian nations upon the American continent. So far as is known, their original home was upon the Atlantic Coast in North Carolina, but by the time Europeans began to settle in that section they had drifted into the Western country. Their first contact with the white race occurred in the upper Mississippi region. These white people were the French explorers who had penetrated into almost every part of the interior long before the English had made any serious attempt at the exploration of the wilderness west of the Allegheny Mountains. The friendly relations between the French and the Sioux continued for many years, but when the French were finally supplanted by the English in most localities, the Sioux made an alliance with the latter which was maintained during the Revolutionary War, and continued until after the War of 1812. Subsequent to the year 1812, the Sioux gradually drifted still farther westward, and not many years later their principal home was upon the upper Missouri River. The recognized southern boundary of their country was the North Platte River, but on account of their friendly relations with the Cheyenne and Arapaho, the Sioux often wandered along the base of the mountains as far as the Arkansas River, and, being at enmity with the Ute, they frequently joined the Cheyenne and Arapaho in raids upon their common enemy.

Pawnee Indians of Colorado

While the Pawnees seldom spent much time in this region, they often came to the mountains in raids upon their enemies the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa and upon horse-stealing expeditions. The Pawnee were members of the Caddoan family, whose original home was in the South. In this they were exceptional, since almost every other tribe in this Western country came from the north or east. From time immemorial their principal villages were located on the Loup Fork of the Platte River and on the headwaters of the Republican River, about three hundred miles east of the Rocky Mountains. The Pawnee were a warlike tribe and extended their raids over a very wide stretch of country, at times reaching as far as New Mexico. They carried on a bitter warfare with the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, and at times were engaged in warfare with almost every one of the surrounding tribes. They were a courageous people, and were generally victorious, where the numbers engaged were at all nearly equal. The Spaniards of New Mexico became acquainted with this tribe as early as 1693, and made strenuous efforts to maintain friendly relations with them; with few exceptions these efforts were successful.

In 1720, the Spanish authorities of New Mexico learned that French traders had established trading stations in the Pawnee country, and were furnishing the Indians with firearms. This news greatly disturbed the Spaniards and resulted in a military expedition being organized at Santa Fe, to visit the principal villages of the Pawnees for the purpose of impressing that tribe with the strength of the Spanish Government, and thus to counteract the influence of the French. The expedition started from Santa Fe in June of that year. It was under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Villazur, of the Spanish regular army, and was composed of fifty armed Spaniards, together with a large number of Jicarilla Apache Indians as auxiliaries, making the expedition an imposing one for the times. The route taken, as nearly as I can determine from the description given in Bancroft’s history of New Mexico, was northerly along the eastern base of the mountains, passing not very far from where Colorado Springs is now located. After reaching the Platte River, at no great distance east of the mountains, the expedition proceeded down the valley of that stream until it came in contact with the Pawnees, but before a council could be held, the latter surprised the Spaniards, killed the commanding officer, and in the fight that ensued almost annihilated the party. The surviving half-dozen soldiers, who were mounted, saved themselves by flight. Not yet having acquired horses, the Pawnees could not pursue them. These survivors, after untold hardships, reached Santa Fe a month or two later to tell the tale. Another instance of a Spanish force visiting the Pawnees occurred in 1806. When Lieutenant Pike on his exploring tour visited the Pawnees on the Republican River in September of that year, he found that a Spanish military force had been there just ahead of him. This force had been dispatched from Santa Fe to prevent him from exploring the country north of the Arkansas River, to which the Spanish Government insistently laid claim. However, the expedition failed of its purpose, inasmuch as it marched back up the Arkansas River to the mountains, and returned to Santa Fe without having seen or heard of Lieutenant Pike.

When Colonel Long on his exploring expedition visited this tribe in 1819, he found the Pawnee mourning the loss of a large number of their warriors who had been killed in an encounter with the Cheyenne and Arapaho in the region adjacent to the Rocky Mountains. It seems that ninety-three warriors left their camp on the Republican River and proceeded on foot to the mountains on a horse-stealing expedition. The party finally reached a point on the south side of the Arkansas River, having up to that time accomplished nothing. Here they were discovered and attacked by a large band of Cheyenne and Arapaho. During the fight that followed, over fifty of the Pawnees were killed; but the attacking party suffered so severely that after the fighting had continued for a day or more, they were glad to allow the surviving Pawnees, numbering about forty, to escape. Most of the latter were wounded and it was with difficulty that they succeeded in reaching their homes.

Culture of the Tribes of the Pike’s Peak Region

All the tribes that I have mentioned were purely nomadic, and, aside from the Pawnees, depended entirely upon game for a living.

The Pawnee were the only tribe that engaged in agriculture. Their summer camps were generally located at some favorable spot for growing corn, beans, pumpkins, and other vegetables. They usually remained at such place until their crops were harvested, when they made large excavations in the ground in which they stored their grain and vegetables for future use. After covering the excavation they carefully obliterated all evidence of it, in order to prevent discovery. They would then go off on hunting expeditions, returning later in the winter to enjoy the fruits of the summer’s toil of their squaws-for the warrior never degraded himself by doing any labor which the squaw could perform. Their habitations, when staying any length of time in one locality, were made of poles, brush, grass, and earth, and were more durable structures than the lodges used by the other tribes of the plains.

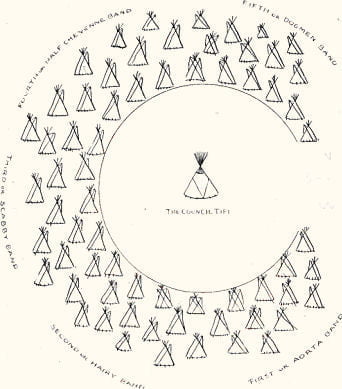

The Ute, Comanche, Kiowa, Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho used the conical wigwam, which was easily erected and quickly taken down. The conical wigwam consisted of a framework of small pine poles about two and one-half inches in diameter and twenty feet in length. In its erection, three poles were tied together about two or three feet from the smaller end; the three poles were then set up, their bases forming a triangle sufficiently far apart to permit of a lodge about twenty feet in diameter. The remaining sixteen to eighteen poles used were then placed in position to form a circle, their bases about four feet apart and their tops resting in the fork of the three original poles. Among the plains Indians, where buffalo were plentiful, the covering for this framework consisted of buffalo skins which had been tanned and sewed together by the squaws. It was so shaped that a flap could be thrown back at the top, leaving an opening through which the smoke could escape, and another at the bottom for use as a door. The bottom of this covering was secured by fastening it to small stakes driven into the ground. All of the bedding, buffalo robes, and other belongings of the Indians were taken into the wigwam and piled around the sides; a small hole was then dug in the center of the earthen floor, in which the fire was built. In taking down the tents, preparatory to moving about the country, the squaws removed the covering from the framework, and folded it into a compact bundle; they took the poles down and laid them in two parallel piles three or four feet apart, and then led a pony in between them. The upper end of each pile was fastened to the pack-saddle, leaving the other end to drag upon the ground. Just back of the pony’s tail the covering of the tent was fastened to the two sets of poles, on top of which the babies and small children were placed. In this way the Indians moved their camps from place to place. The squaws did all the work of making these tent coverings, procuring the poles, setting up the tents, and taking them down. The warrior never lifted his hand to help, as it was beneath the dignity of a warrior to do any kind of manual labor.

Among the favorite camping-places of the Indians in El Paso County, Colorado, the region extending along the west side of Cheyenne Creek just above its mouth was probably used most frequently. There were evidences of other camping places at different points farther up the creek, that had been used to a lesser extent. Their tent-poles, in being dragged over the country, rapidly wore out, and for that reason the Indians of the plains found it necessary to come to the mountains every year or two to get a new supply. The thousands of small stumps that were to be seen on the side of Cheyenne Mountain at the time of the first settlement of this region gave evidence that many Indians had secured new lodge poles in that locality. It is probable that this was the reason why their tents were so often pitched in the valley of Cheyenne Creek, and undoubtedly this is the origin of the name by which the creek is now known.

On account of its close proximity to the country of the Ute, the Indians of the plains must necessarily have had to come to this locality in very considerable force and must at all times have kept a very sharp lookout in order to avoid disaster. It is known that the Ute maintained pickets in this vicinity much of the time. In the early days, any one climbing to the top of the high sandstone ridge back of the United States Reduction Works at Colorado City might have seen numerous circular places of defense built of loose stone, to a height of four or five feet, and large enough to hold three or four men comfortably. These miniature fortifications were placed at intervals along the ridge all the way from the Fountain to Bear Creek and doubtless were built and used by the Ute. From these small forts, the Indian pickets could overlook the valley of the Fountain, the Mesa, and keep watch over the country for a long distance out on the plains. At such times as the Ute maintained sentinels there it would have been difficult for their enemies to reach this region without being discovered.