Pawnee Indians. A confederacy belonging to the Caddoan family. The name is probably derived from parika, a horn, a term used to designate the peculiar manner of dressing the scalp-lock, by which the hair was stiffened with paint and fat, and made to stand erect and curved like a horn. This marked features of the Pawnee gave currency to the name and its application to cognate tribes. The people called themselves Chahiksichahiks, `men of men.’

In the general northeastwardly movement of the Caddoan tribes the Pawnee seem to have brought up the rear. Their migration was not in a compact body, but in groups, whose slow progress covered long periods of time. The Pawnee tribes finally established themselves in the valley of Platte River, Nebraska, which territory, their traditions say, was acquired by conquest, but the people who were driven out are not named. It is not improbable that in making their way north east the Pawnee may have encountered one or more waves of the southward movements of Shoshonean and Athapascan tribes. When the Siouan tribes entered Platte valley they found the Pawnee there. The geographic arrangement always observed by the four leading Pawnee tribes may give a hint of the order of their northeastward movement, or of their grouping in their traditional southwestern home. The Skidi place was to the north west, and they were spoken of as belonging to the upper villages; the Pitahauerat villages were always downstream; those of the Chaui, in the middle, or between the Pitahauerat and the Kitkehahki, the villages of the last-named being always upstream. How long the Pawnee resided in the Platte valley is unknown, but their stay was long enough to give new terms to ‘west’ and ‘east,’ that is, words equivalent to ‘up’ or ‘down’ that eastwardly flowing stream.

Pawnee Indians History

The earliest historic mention of a Pawnee is that of the so-called “Turk”, who by his tales concerning the riches of Quivira allured and finally led Coronado, in 1541, from New Mexico over the plains as far as Kansas, where some Pawnee 1 visited him. The permanent villages of the tribes lay to the north of Quivira, and it is improbable that Coronado actually entered any of them during his visit to Quivira, a name given to the Wichita territory. It is doubtful if the Apane or the Quipana mentioned in the narrative of De Soto’s expedition in 1541 were the Pawnee, as the latter dwelt to the north west of the Spaniards’ line of travel. Nor is it likely that the early French explorers visited the Pawnee villages, although they heard of them, and their locality was indicated by Tonti, La Harpe, and others. French traders, however, were established among the tribes before the middle of the 18th century.

How the term Pani, or Pawnee, as applied to Indian slaves, came into use is not definitely known. It was a practice among the French and English in the 17th and 18th centuries to obtain from friendly tribes their captives taken in war and to sell them as slaves to white settlers. By ordinance of Apr. 13, 1709, the enslavement of Blacks and Pawnee was recognized in Canada 2. The Pawnee do not seem to have suffered especially from this traffic, which, though lucrative, had to be abandoned on account of the animosities it engendered. The white settlers of New Mexico became familiar with the Pawnee early in the 17th century through the latter’s raids for procuring horses, and for more than two centuries the Spanish authorities of that territory sought to bring about peaceful relations with them, with only partial success.

As the Pawnee villages lay in a country remote from the region contested by the Spaniards and French in the 17th and 18th centuries, these Indians escaped for a time the influences that proved so fatal to their congeners, but ever-increasing contact with the white race, in the latter part of the 18th century, introduced new diseases, and brought great reduction in population together with loss of tribal power. When the Pawnee territory, through the Louisiana Purchase, passed under the control of the U. S., the Indians came in close touch with the trading center at St Louis. At that time their territory lay between the Niobrara river on the north and Prairie Dog creek on the south, and was bounded on the west by the country of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, and on the east by that of the Omaha, on the north of the Platte, and on the south of the Platte by the lands of the Oto and Kansa tribes. The trail to the south west, and later that across the continent, ran partly through Pawnee land, and the increasing travel and the settlement of the country brought about many changes.

Through all the vicissitudes of the 19th century the Pawnee never made war against the U. S. On the contrary they gave many evidences of forbearance under severe provocation by waiting, under their treaty agreement, for the Government to right their wrongs, while Pawnee scouts faithfully and courageously served in the U. S. army during Indian hostilities. The history of the Pawnee has been that common to reservation life the gradual abandonment of ancient customs and the relinquishment of homes before the pressure of white immigration.

The first treaty between the Pawnee and the U. S. was that of the several bands made at St Louis, June 18-22, 1818 3, when peace was concluded with all the tribes of the region disturbed by the War of 1812. By treaty of Ft Atkinson (Council Bluffs), Iowa, Sept. 28, 1825, the Pawnee acknowledged the supremacy of the U. S. and agreed to submit all grievances to the Government for adjustment. By treaty of Grand Pawnee Village, Nebraska, Oct. 9, 1833, they ceded all their lands south of Platte river. By that of Ft Childs, Nebraska, Aug. 6, 1848, they sold a 60-mile strip on the Platte about Grand Island. By treaty of Table creek, Nebraska, Sept. 24, 1857, all lands north of the Platte were assigned to the Government, except a strip on Loup river 30 miles east and west and 15 miles north and south, where their reservation was established. This tract was ceded in 1876, when the tribes removed to Oklahoma, where they now live. In 1892 they took their lands in severalty and became citizens of the U. S.

Pawnee Indians Culture

The tribal organization of the Pawnee was based on village communities representing subdivisions of the tribe. Each village had its name, its shrine containing sacred objects, and its priests who had charge of the rituals and ceremonies connected with these objects; it had also its hereditary chiefs and its council composed of the chiefs and leading men. If the head chief was a man of unusual character and ability he exercised undisputed authority, settled all difficulties, and preserved social order; he was expected to give freely and was apt to be surrounded by dependents. Each chief had his own herald who proclaimed orders and other matters of tribal interest.

The tribe was held together by two forces: the ceremonies pertaining to a common cult in which each village had its place and share, and the tribal council composed of the chiefs of the different villages. The confederacy was similarly united, its council being made up from the councils of the tribes. In the meetings of these councils rules of precedence and decorum were rigidly observed. No one could speak who was not entitled to a seat, although a few privileged men were permitted to be present as spectators. The council determined all questions touching the welfare of the tribe or of the confederacy.

War parties were always initiated by some individual and were composed of volunteers. Should the village be attacked, the men fought under their chief or under some other recognized leader. Buffalo hunts were tribal, and in conducting them officers were appointed to maintain order so as to permit each family to procure its share of the game. The meat was cut in thin sheets, jerked, and packed in parflêche cases for future use. Maize, pumpkins, and beans were cultivated. The maize, which was regarded as a sacred gift, was called “mother,” and religious ceremonies were connected with its planting, hoeing, and harvesting. Basketry, pottery, and weaving were practiced.

The Pawnee house was the earth lodge, the elaborate construction of which was accompanied with religious ceremony, and when after an absence from home the family returned to their dwelling the posts thereof were ceremonially anointed. Men shaved the head except for a narrow ridge from the forehead to the scalp-lock, which stood up like a horn. Frequently a scarf was tied around the head like a turban. Both beard and eyebrows were plucked; tattooing was seldom practiced. The breech cloth and moccasins were the only essential parts of a man’s clothing; leggings and robe were worn in cold weather and on gala occasions. Face painting was common, and heraldic designs were frequently painted on tent covers and on the robes and shields of the men. Women wore the hair in two braids at the back, the parting as well as the face being painted red. Moccasins, leggings, and a robe were the ancient dress, later a skirt and tunic were worn. Descent was traced through the mother. There were no totems belonging to the confederacy. After marriage a man went to live with his wife’s family. Polygamy was not uncommon.

Pawnee Indians Religion

The religious ceremonies were connected with the cosmic forces and the heavenly bodies. The dominating power was Tirawa, generally spoken of as “father.” The heavenly bodies, the winds, thunder, lightning, and rain were his messengers. Among the Skidi the morning and evening stars represented the masculine and feminine elements, and were connected with the advent and the perpetuation on earth of all living forms. A series of ceremonies relative to the bringing of life and its increase began with the first thunder in the spring and culminated at the summer solstice in human sacrifice, but the series did not close until the maize, called “mother corn,” was harvested. At every stage of the series certain shrines, or “bundles,” became the center of a ceremony. Each shrine was in charge of an hereditary keeper, but its rituals and ceremonies were in the keeping of a priesthood open to all proper aspirants. Through the sacred and symbolic articles of the shrines and their rituals and ceremonies a medium of communication was believed to be opened between the people and the supernatural powers, by which food, long life, and prosperity were obtained. The mythology of the Pawnee is remarkably rich in symbolism and poetic fancy, and their religious system is elaborate and cogent. The secret societies, of which there were several in each tribe, were connected with the belief in supernatural animals. The functions of these societies were to call the game, to heal diseases, and to give occult powers. Their rites were elaborate and their ceremonies dramatic.

Messrs Dunbar and Allis of the Presbyterian church established a mission among the Pawnee in 1834, which continued until 1847 when it was abolished owing to tribal wars. In 1883 the Woman’s National Indian Association established a mission on the Pawnee reservation in Oklahoma, which in 1884 was transferred to the Methodist Episcopal Church, under whose auspices it is still in operation.

Pawnee Confederacy

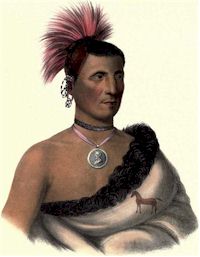

A Pawnee Chief

Four tribes of the Pawnee confederacy still survive: the Chaui or Grand Pawnee, the Kitkehahki or Republican Pawnee, the Pitahauerat or Tapage Pawnee, and the Skidi or Wolf Pawnee.

In 1702 the Pawnee were estimated by Iberville at 2,000 families. In 1838 they numbered about 10,000 souls, according to an estimate by houses by the missionaries Dunbar and Allis, and the estimate is substantially confirmed by other authorities of the same period, one putting the number as high as 12,500. The opening of a principal emigrant trail directly through the country in the 40’s introduced disease and dissipation, and left the people less able to defend themselves against the continuous attacks of their enemies, the Sioux Indians. In 1849 they were officially reported to have lost one-fourth their number by cholera, leaving only 4,500. In 1856 they had increased to 4,686, but 5 years later were reported at 3,416. They lost heavily by the removal to Indian Territory in 1873-75, and in 1879 numbered only 1,440. They have continued to dwindle each year until there are now (1906) but 649 survivors. 4

Citations:

- see Harahey[↩]

- Shea’s Charlevoix, History and General Description of New France, V, 224, 1871[↩]

Treaties made at St. Louis from 18-22 June, 1818.

[↩]

- Hodge, Frederick Webb, Compiler. The Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office. 213-216. 1906.[↩]